University develops virtual engineer

Computer program developed by Portsmouth researchers to predict when machines break down.

Researchers at Portsmouth University have developed a system that claims to be able to predict mechanical failure in industrial machinery.

The system combines computer software with constant monitoring of the plant. Researchers placed sensors on the parts of machines that are most vulnerable to wear and tear, and connected them to software that analyses their status and predicts when a part might fail.

The aim is to cut production downtime by allowing factory owners to replace worn components in machines before they fail. Avoiding unscheduled shut downs can potentially save large sums of money, according to the research team.

"The machines in many processing plants and factories are running day and night and an unscheduled stoppage can cause havoc and can result in huge costs," said Dr David Brown, head of Portsmouth's Institute of Industrial Research.

"This new diagnostic system prevents potential mechanical failure by identifying the faulty or worn out part before it causes a problem."

By giving factory managers advanced warning of failing parts, they can schedule replacement during planned production downtime, which in turn reduces the impact on the factory's supply chain. Increasingly, manufacturers are looking for "zero fault" machines, because their customers cannot tolerate a disruption to supplies.

Building the system, though, required both the use of advanced sensors and some of the latest IT techniques. High-end manufacturing machinery is frequently custom-built for the user. Dr Brown's team had to design the virtual engineer software to be adaptive, so it could learn the precise operations of every piece of plant. The system also relies on data analysis to predict when a wearing part might fail.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

The system has been tested by Stork Food & Dairy Systems (SFDS), a company that builds machinery for the food processing industry.

"An unplanned stoppage on a production line can be a total disaster," said Luke Axel-Berg, general manager at SFDS. "It can spell chaos for a processing plant, especially a dairy plant where milk is literally arriving every single day. The cows don't stop producing milk because a machine has broken."

The university hopes that the system will also help industry by reducing the number of service engineers who need to be kept on call.

-

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?AI PCs are fast becoming a business staple and a surefire way to future-proof your business

By Bobby Hellard

-

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiatives

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiativesNews Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI have announced the launch of two new channel growth initiatives focused on the managed security service provider (MSSP) space and AWS Marketplace.

By Daniel Todd

-

What the US-China chip war means for the tech industry

What the US-China chip war means for the tech industryIn-depth With China and the West at loggerheads over semiconductors, how will this conflict reshape the tech supply chain?

By James O'Malley

-

The Forrester Wave™: Third party risk management platforms

The Forrester Wave™: Third party risk management platformsWhitepaper The 12 providers that matter the most and how they stack up

By ITPro

-

Apple to shift MacBook production to Vietnam in further step away from China

Apple to shift MacBook production to Vietnam in further step away from ChinaNews The plan has been reportedly been worked on for two years, with the tech giant already having a test production site in the country

By Zach Marzouk

-

Food and beverage traceability

Food and beverage traceabilityWhitepaper Understanding food and beverage manufacturing compliance and traceability

By ITPro

-

Ensuring compliance with the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard (NBFDS)

Ensuring compliance with the National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard (NBFDS)Whitepaper How food manufacturers can enhance traceability with technology to be compliant

By ITPro

-

The future of manufacturing

The future of manufacturingWhitepaper Digitally transform your business and get ready for Industry 4.0

By ITPro

-

Microsoft targets optimised supply chain investments with new platform launch

Microsoft targets optimised supply chain investments with new platform launchNews Microsoft's new Supply Chain Platform fully harnesses Microsoft cloud to help businesses improve supply chain agility and resilience

By Daniel Todd

-

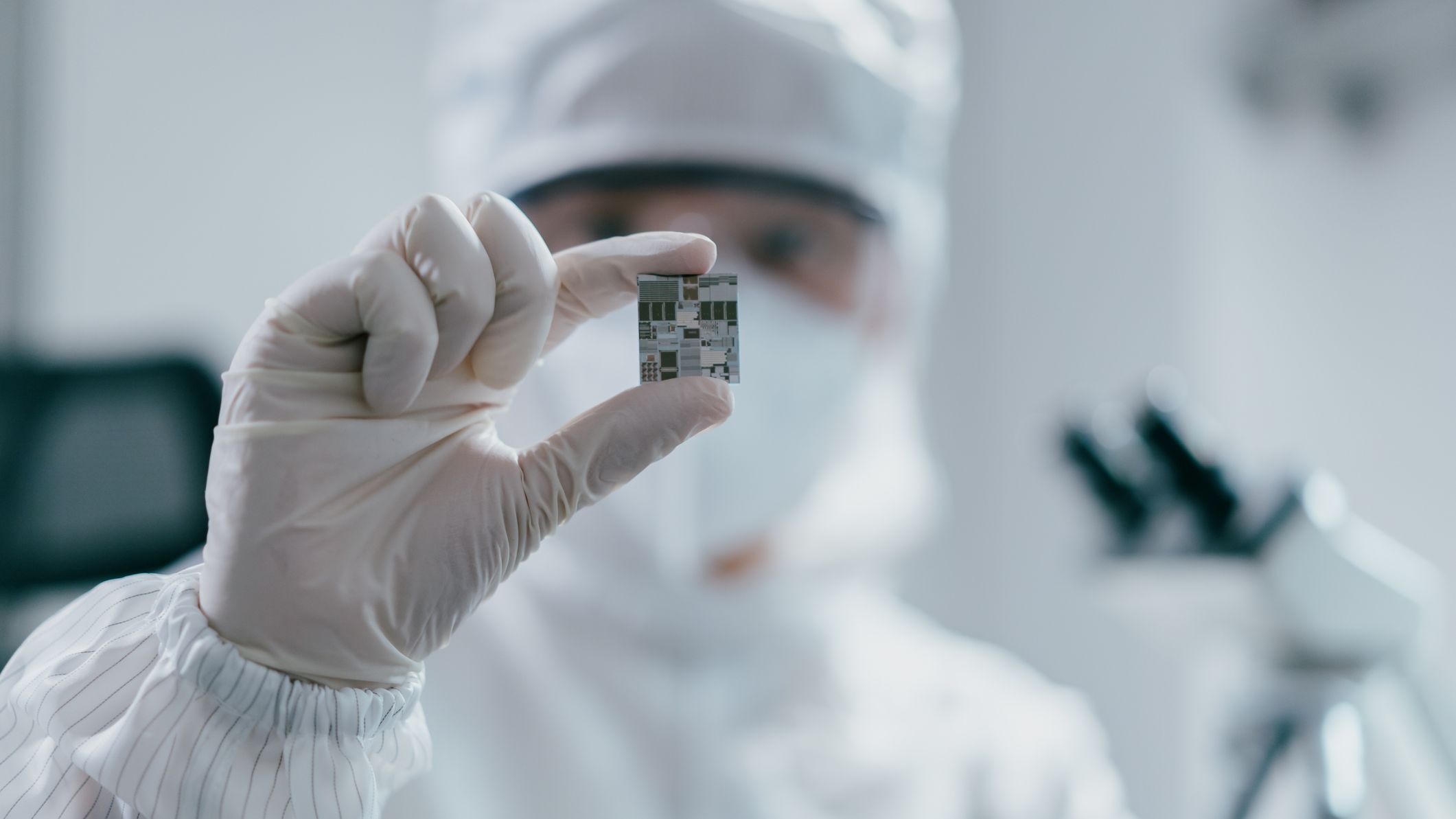

Micron to invest historic $100 billion in NY semiconductor site

Micron to invest historic $100 billion in NY semiconductor siteNews Construction on the site will commence in 2024, with output expected in the late 2020s

By Rory Bathgate