How much is your data worth? And can you turn it into cash?

One solicitor, one futurist and one adtech specialist join forces to answer two questions that will rumble through the next decade

If you’ve ever wondered if your data could be converted into cash, then we have the answer. In fact, we have two. The first is a simple “yes”; in fact, it’s happening right now. The more accurate, and more nuanced, answer? Yes, but not in the way that you’re probably thinking.

Who owns our data?

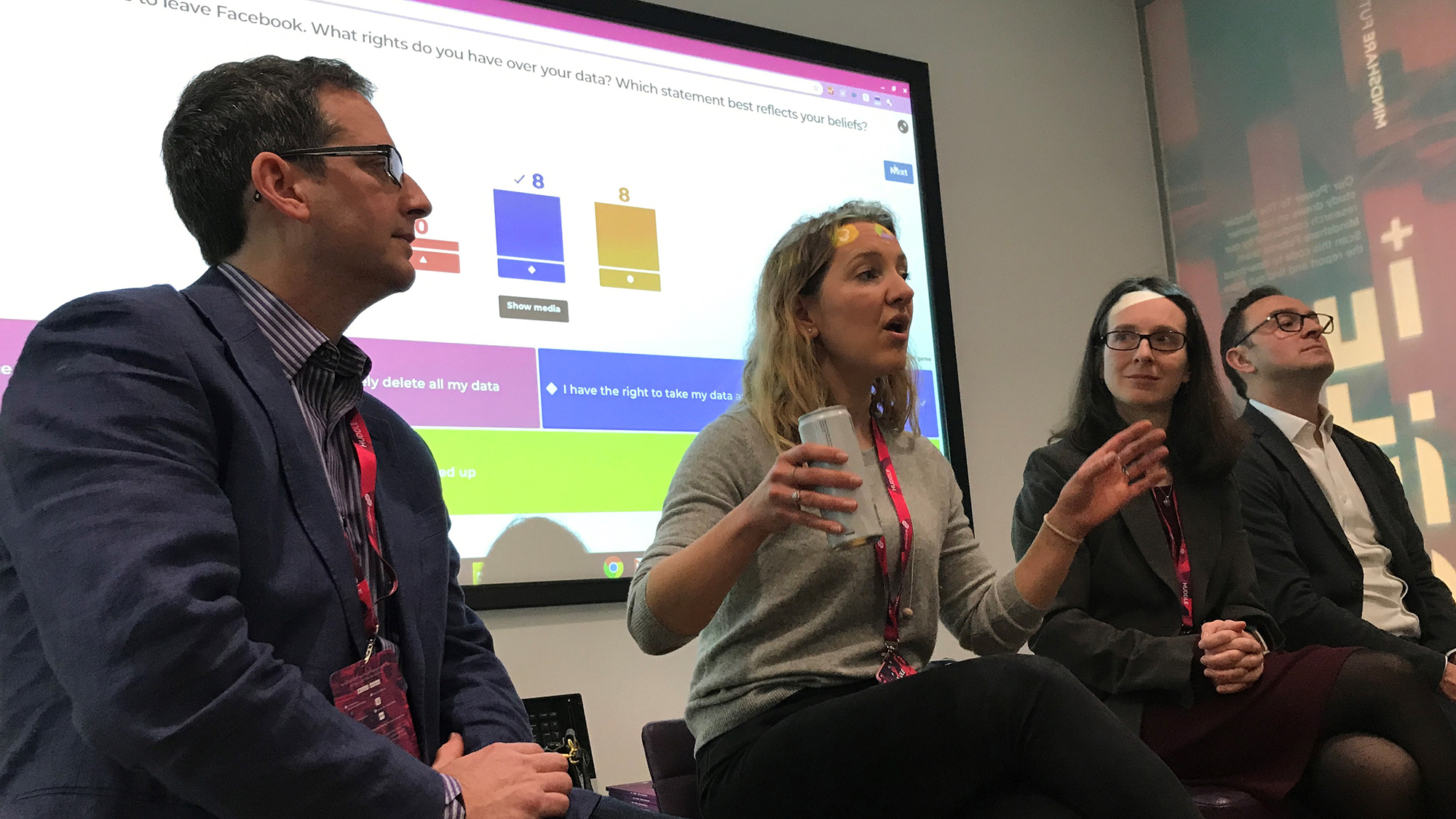

The first challenge is that data isn’t something that can be legally owned. “You can have a bundle of intellectual property rights surrounding data,” said Olivia Whitcroft, a solicitor who specialises in data protection and intellectual property, speaking at this year’s Group M Huddle.

“So [we have] database rights, copyright rights around data,” explained Whitcroft. “The data protection laws say how you can use data and give individual rights to the data, but you can't actually own data. Yet there is a value placed on it - it’s unusual!”

Applied futurist Tom Cheesewright, speaking at the same event, pointed out that the market value is still surprisingly low. “If you go on to the dark web and you want to buy credit card CVVs so you can actually go and use it, it’s about £5. A full identity with someone’s social security and everything else is only about £30. So you can go and do full identity theft for £30.”

Chloe Grutchfield, co-founder of adtech specialist RedBud Partners, saw things through a more practical prism. “Let’s imagine that the average CPM [cost per mille, so 1,000 ads] is £5. It’s probably a lot lower than that. And then I will be exposed to 1,000 ads per day.”

Sadly, that doesn’t mean you’re going to get £5: once various companies have taken their cut, the direct “value” to the advertiser will be closer to £1. This then needs to go through the rewarding systems so that Chloe can reap her rewards. “I would get maximum - maximum - per day, 50p. So, not bad per year, but I’m going to have to sign up to several reward systems to even get that.”

Context equals cash

As Cheesewright was quick to point out, it’s all about the context. “In advertising terms, your data is worth very little. Against a purchase, it’s worth a relatively large amount.” As an active example, he pointed to Quidco. “The average reward for a Quidco user is about £280 a year.”

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

While it’s morally straightforward - and well-established - to claim the equivalent of cashback on products, things become more murky when the sale is more personal. “I remember one agency wanted to target people who had arthritis using location-based data,” said Grutchfield, “and from an ethical perspective I said no.”

The subject of ethics is a key one for Whitcroft. “Data protection derives from privacy and human rights laws, and that’s why we have it in place: to protect people’s fundamental rights,” she explained.

“When we start selling data, are we starting to infringe on those fundamental human rights? More vulnerable people, poorer people will perhaps be affected more because they're forced to sell their data because it’s a way to earn cash.

“Similarly, the big tech giants will be able to afford to pay people for their data, may use it for good purposes or may use it for their own business purposes, and then there may be smaller health companies who could really benefit from knowing people’s data to improve public health and they won’t be able to afford it.”

What happens next?

So what does our future look like? Who better to ask than a futurist? “Most businesses that have built a model of monetising a central store of data die. That includes social networks for me.”

If you own Facebook stocks, look away now: “All social networks fundamentally do the same thing,” explained Cheesewright. “They do one-on-one communication, they do one-to-many communication, the sharing of rich media. Do we need Facebook to own the infrastructure to do that or could we all have a standards-based client that could interact and share on a use-case basis?”

Cheesewright sees a future where that makes it easier to apply value to data without having to worry about the thorny issue of property rights, but admits that this is likely to take more than five years to evolve.

One thing is clear. We’re at the start of the journey here, and new services like Brave - a browser that currently blocks ads and website trackers, but last week announced an opt-in service where viewers would be paid in “tokens” for viewing ads from their own ad network - are interesting experiments rather being necessarily the future.

And we have still barely scraped the surface of where human rights sit in this data-driven world. “There are a lot of ethical issues to work out if selling data becomes a bigger thing,” said Whitcroft.

Tim Danton is editor-in-chief of PC Pro, the UK's biggest selling IT monthly magazine. He specialises in reviews of laptops, desktop PCs and monitors, and is also author of a book called The Computers That Made Britain.

You can contact Tim directly at editor@pcpro.co.uk.

-

Google Cloud is leaning on all its strengths to support enterprise AI

Google Cloud is leaning on all its strengths to support enterprise AIAnalysis Google Cloud made a big statement at its annual conference last week, staking its claim as the go-to provider for enterprise AI adoption.

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Marketing talent brain drain could stunt channel partner success

Marketing talent brain drain could stunt channel partner successNews Valuable partner marketing skills are at risk of being lost as the structure of channel marketing teams continues to shift, according to new research.

By Daniel Todd Published

-

Automate personalization with AWS

Automate personalization with AWSWhitepaper How marketers can automate, deliver, and analyze billions of personalized messages and offers per day

By ITPro Published

-

Schneider Electric unveils its first e-commerce partner program

Schneider Electric unveils its first e-commerce partner programNews Partners will be assigned a dedicated Schneider expert to aid strategy development

By Daniel Todd Published

-

How digital marketing will evolve beyond social media

How digital marketing will evolve beyond social mediaIn-depth Twitter's ongoing destabilisation proves businesses can't rely on social media for digital marketing forever

By Elliot Mulley-Goodbarne Published

-

Twilio tackles 'crucial' customer retention with trio of platform upgrades

Twilio tackles 'crucial' customer retention with trio of platform upgradesNews The company believes that retaining customers and maximising LTV is crucial in weathering the current macroeconomic headwinds

By Connor Jones Published

-

Activation playbook: Deliver data that powers impactful, game-changing campaigns

Activation playbook: Deliver data that powers impactful, game-changing campaignsWhitepaper Bringing together data and technology to drive better business outcomes

By ITPro Published

-

The digital marketer’s guide to contextual insights and trends

The digital marketer’s guide to contextual insights and trendsWhitepaper How to use contextual intelligence to uncover new insights and inform strategies

By ITPro Published

-

Twitter sells mobile ad unit for triple its original value

Twitter sells mobile ad unit for triple its original valueNews The sale will allow the tech giant to focus on its plans of doubling its revenue in 2023 to $7.5 billion

By Sabina Weston Published