Why does Japan lag behind on startups?

The country has a reputation as a tech leader, but its startup ecosystem has yet to achieve its potential

Japan is globally regarded as technologically ahead of the game, being the birthplace of huge players including Sony and Toshiba – yet the country has tended to be unsupportive of startups. Now though the period of Abenomics seems to have come to an end, with a new election on the horizon and the current prime minister promising to establish a £637 million fund for advanced technology: Could this be the turning point for Japanese startups?

Crunching the numbers

Compared to other developed nations, Japan has few unicorn companies and low levels of startup funding, says Harunori Oiwa, ventures associate at Plug and Play – an organisation dedicated to linking startups with more established companies, particularly in Japan. Oiwa points out that, according to CB Insights, there are over 800 unicorns around the world as of October 2021, but only six of them are in Japan. By comparison, there are 432 in the USA.

He adds that, in 2020, the total amount of venture capital (VC) investment in the US was around $166 billion, compared to just $1.5 billion in Japan – a 110-fold difference. And the number of deals made in the US during 2020 was 12,254, compared to Japan’s 1,160.

To help grow the startup ecosystem, Oiwa believes Japanese startups need to be seen as an investment asset for overseas investors. Ideally, startups should not merely aim for a small initial public offering (IPO) in their native market, but should develop their business with a view to being acquired by overseas companies. One startup leading the way is Spiber, which raised $312 million in funds from global private equity firm Carlyle this year. “This is the group's first non-buyout minority investment, which is very rare,” Oiwa explains.

Things are looking up, however. Startup funding in Japan totalled $3 billion in the first half of 2021, whereas there was just $5 billion in funding for the whole of 2020, says Kenichiro Hara, principal at venture capital firm DCM. That’s a threefold increase since 2016, and ten times the amount of funding provided a decade ago.

Yet the figures are still small relative to the size of the market: South Korea, with a third of Japan’s GDP, has seen $4 billion in VC investment. This is partly down to a lack of late-stage mega-deals: Japan saw just two $100 million+ funding rounds in the whole of 2020, and only six in the first half of 2021. “If we see an increase in later-stage deals, the growth of startups and their successes will definitely accelerate,” Hara says.

Taking on the world

Another negative factor for the Japanese startup scene is that, traditionally, starting a company or joining a startup was not considered an attractive career path for the country's students, says Masaya Kubota, partner at Japan's largest VC firm, World Innovation Lab (WiL). Risk-taking was not encouraged, failures were severely stigmatised, and banks were reluctant to invest in new ventures.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

“One of the major reasons why Japan lags behind is the lack of self-reinforcing mechanisms between innovators and financiers that we have seen in places like Silicon Valley,” he says.

This has been changing, however, as large corporations began to lose their status and are seen to be no longer taking the lead on technological innovation. Kubota points out, too, that Japanese startups tend to focus on the domestic market – but with the entry barriers for foreign companies wanting to invest in the country falling away, this may in turn offer Japanese companies an opportunity to compete on a global scale.

Indeed, there are an increasing number of top-tier investors worldwide looking for opportunities. Corporate VC (CVC) activities in Japan have grown fivefold between 2013 and 2018, and startups are raising record amounts of money.

The Japanese government is providing incentives too, ranging from tax breaks for corporates investing into startups to national funds like the Japan Investment Corporation, which has a budget over $20 billion.

To help the startup ecosystem, Kubota says continued financial and business support from the government is needed, along with an increase in large corporations’ involvement in investing in and using startup services.

Breaking out of the mould

Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1960s and 70s fostered a general sense that the best career path was to graduate from a prestigious university and work for a blue-chip company, according to Masako Eguchi-Bacon, CEO and founder of Ocean Bridge Management. During this period, most large companies offered a good salary and lifetime employment.

Even so, she notes that the late 1990s did see the emergence of a startup culture in Japan, as elsewhere, with one famous IT startup cluster in the Shibuya area of Tokyo known as Bit Valley.

Over the last five years, startups have again become a significant focus. Japanese government agencies, both central and local, have launched various support programmes and as technology development has accelerated, many major businesses have realised they need to look for innovative technologies and ideas from outside the organisation, leading them to engage more with startups.

“This time, I think, it will not just be a ‘trendy boom’. Startups will play an important role in Japanese society,” says Eguchi-Bacon.

She adds that since there weren’t previously many startups in the country, there has been a lack of experienced investors – but this is changing. As startups have become more important, local companies have started to set up CVCs, leading to an influx of Japanese VCs and angel investors in addition to growing numbers of non-Japanese investors.

Japanese startups also face a major challenge in finding the right talent, says Joshua Flannery, founder and CEO of Innovation Dojo Japan. He notes that not only do new ventures require engineers and other skilled partners, to compete on the global stage, they also need English-language skills and cross-cultural communication experience – and these aren’t always found in the average startup founder or employee.

Indeed, due to a long-term domestic focus within Japanese industry, global practices and frameworks for growing businesses have only recently been introduced into accelerators and incubators. Those efforts have been primarily carried out by foreign players, such as Rainmaking from the UK (via Startupbootcamp), Plug and Play from the US, or Innovation Dojo from Australia.

RELATED RESOURCE

Shining light on new 'cool' cloud technologies and their drawbacks

IONOS Cloud Up! Summit, Cloud Technology Session with Russell Barley

Japan’s startup environment is already strong in one area: The country has one of the largest pools of corporate capital floating around the ecosystem for startup investment and M&A deals, reveals Flannery. While the number of startups receiving funding has been declining, the amount raised per startup is increasing significantly. In 2021, the top three deals were $142.5 million into cloud based HR software company SmartHR, $230 million into mediatech company SmartNews and an acquisition of $2.7 billion into fintech company Paidy.

“The area in need of most attention is the pre-seed and seed stage, where in other markets angel investors and other very early-stage investors are active,” Flannery explains, adding that while some angel investors do exist in Tokyo, the number of deals is relatively low, and outside Tokyo is rarely heard of.

Nevertheless, Flannery believes things are rapidly improving. The government’s has nominated several locations as official “startup cities”, and given funding to them to strengthen their startup ecosystems. In Kobe, it has invested in a digital platform called Kobe Startup Hub to help members of the startup sector connect with each other. In late August this year, it launched the Global Mentorship Programme, aiming to nurture 200 startups by March 2022 and at least 1,000 by 2025.

Flannery says that what’s now needed is an effort to help graduates get startup-ready and prepare them for the future of work. He also argues that paths need to be forged to help foreigners enter Japan and grow the pool of available talent.

Finally, he recommends that more education and support for angel and early-stage investors are needed to help young companies flourish and the concept of starting or working in a startup needs to be normalised, with entrepreneurism recognised as a critical piece of Japan’s future economy.

Zach Marzouk is a former ITPro, CloudPro, and ChannelPro staff writer, covering topics like security, privacy, worker rights, and startups, primarily in the Asia Pacific and the US regions. Zach joined ITPro in 2017 where he was introduced to the world of B2B technology as a junior staff writer, before he returned to Argentina in 2018, working in communications and as a copywriter. In 2021, he made his way back to ITPro as a staff writer during the pandemic, before joining the world of freelance in 2022.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Is Rishi Sunak’s ‘Unicorn Kingdom’ a reachable goal or a mere pipedream?

Is Rishi Sunak’s ‘Unicorn Kingdom’ a reachable goal or a mere pipedream?Analysis Plunging venture capital investment and warnings over high-growth company support raise doubts over the ‘Unicorn Kingdom’ ambition

By Ross Kelly Published

-

Some Tech Nation programs could continue after Founders Forum acquisition

Some Tech Nation programs could continue after Founders Forum acquisitionNews The acquisition brings to a close a months-long saga over what the future holds for Tech Nation initiatives

By Ross Kelly Published

-

Podcast transcript: Startup succession: From Tech Nation to Eagle Labs

Podcast transcript: Startup succession: From Tech Nation to Eagle LabsIT Pro Podcast Read the full transcript for this episode of the ITPro Podcast

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

The ITPro Podcast: Startup succession: From Tech Nation to Eagle Labs

The ITPro Podcast: Startup succession: From Tech Nation to Eagle LabsITPro Podcast Some small firms are already lamenting the loss of Tech Nation, but Barclays Eagle Labs has much to offer the sector

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Don’t count Barclays Eagle Labs out just yet – it can deliver in ways Tech Nation never has

Don’t count Barclays Eagle Labs out just yet – it can deliver in ways Tech Nation never hasOpinion Tech Nation has a great track record, but Eagle Labs has the experience, the financial clout, and a clear-cut vision that will deliver positive results for UK tech

By Ross Kelly Published

-

UK tech sector could face a ‘unicorn winter’ amid spiralling economic conditions

UK tech sector could face a ‘unicorn winter’ amid spiralling economic conditionsNews Tech Nation’s final piece of industry research calls for action to support continued ecosystem growth

By Ross Kelly Published

-

"It's still not great": Industry divided on government's SMB tax relief package

"It's still not great": Industry divided on government's SMB tax relief packageNews The government’s handling of R&D tax credits has left SMBs with a “sense of disbelief”

By Ross Kelly Published

-

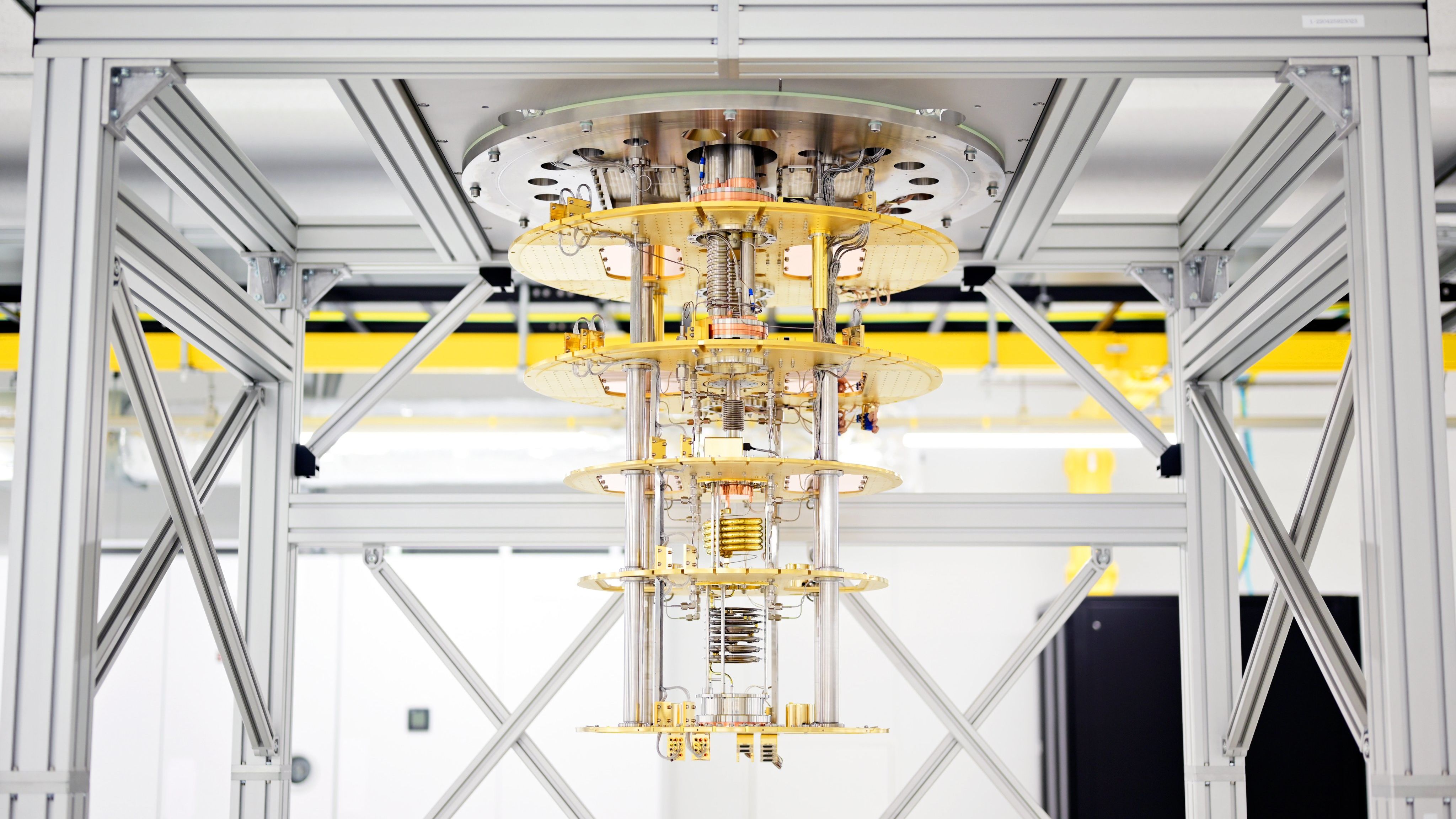

UK startup's Equinix deal marks step towards broad quantum computing access

UK startup's Equinix deal marks step towards broad quantum computing accessNews Businesses around the world will be able to use its quantum computing as a service platform through Equinix

By Zach Marzouk Published