Big tech's internal uprising

Whether it's over military tech or social issues, major tech companies are struggling to cope with mutiny in ranks

At some point in the past decade, the world fell out of love with big tech. Companies such as Google, Amazon and Facebook today find themselves routinely on the receiving end of near-constant negative news stories, and are regularly berated by politicians. The ‘evil tech CEO’ has even become a major villain archetype in Hollywood movies.

The criticism isn’t just coming from the outside, though. Recent years have seen a number of campaigns run by big tech’s own employees, criticising their bosses over a wide range of issues. A string of whistleblowers have also emerged, meanwhile, revealing what’s going on inside some of the world’s largest companies.

Strikingly, the protests cover a wide range of issues. Military links are a common source of tension, for example, as Microsoft learned when employees publicly protested a $480m contract the company signed to develop HoloLens technology for the US military. Amazon and Google staffers have been similarly outspoken against a cloud computing data centre project for the Israeli Defence Force.

Traditional labour issues have also caused tension, most notably with Amazon’s large warehouse workforce campaigning for better pay and conditions, but also in Silicon Valley, as Apple discovered when staff organised to campaign against plans to force employees to return to post-pandemic work in the office.

Perhaps, though, the most explosive area of employee activism has been on social issues. In 2018, Google employees walked out over a controversial memo criticising “Google’s ideological echo chamber” regarding the company’s diversity policies. More recently, Facebook has found itself in the firing line for its influence on the wider world, following a leak of documents by whistleblower Francis Haugen, while Netflix staff walked out following the broadcast of a comedy special by Dave Chapelle over the comedian’s controversial stance on transgender issues. What has triggered this wave of action, and why are the workers of Silicon Valley revolting?

Don’t be evil

“If you go back ten to 15 years ago, some of these companies acted as if they were a new type of company, like, enlightened in some way,” says professor Janice Bellace, who studies international labour law and business ethics at the Wharton Business School in Pennsylvania. “Well, it hasn't worked out that way, quite clearly. I guess, for some people, this is a surprise, a shock and leads to disillusionment.”

She gives the example of Google’s famous mantra ‘Don’t be evil’, pointing to how for all of the platitudes, Google is ultimately just like every other profit-making company. “It's listed on the stock market, and made tonnes of money for the founding people,” she says.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

This accords with one account we heard from a Google insider – an engineer whose identity we’re concealing – who participated in the walkout over the diversity memo. “A lot of it also has to do with just the growth of the company and things becoming, by nature, a little bit less open,” they say.

Part of the reason why big tech is, in particular, the focus of employee protests could be linked to the corporate culture in Silicon Valley. “The culture has always been that management [can be] challenged from any level,” says the insider. “Everyone is always encouraged to speak up and challenge anything that comes from above. I guess the walkout was maybe a bit of a tipping point where a couple of [grievances] combined.”

Not looking after themselves

One of the most striking aspects of the current activism is, unlike traditional worker uprisings, which were mostly concerned with issues such as pay and material working conditions, the most high profile incidents of recent times were the result of workers concerned about the impact of their employer on the wider world.

RELATED RESOURCE

“In a way [big tech employees] are in a unique position,” says professor Athina Karatzogianni, who researches social movements and digital technology at the University of Leicester. “They're highly educated, they're people that went to Harvard, they’re skilled people that are thinking it's not enough to just make money here, we need to see what is happening, what is the impact of this.”

This is also reflected in what our Google insider tells us. “I would say most people are somewhat pragmatic about it,” they say. “They have an attitude along the lines of, well, Google's turning a profit and not everything Google does is rosy and only good for the world and like everything there are challenges. But equally, they feel on balance, it's still a force for good and a good place to work.”

The irony is this sort of introspection may be a consequence of the platforms and products that big tech has created itself. “There's more of this dissatisfaction bubbling up, and people feeling that they should speak out,” says Bellace. “Obviously, social media makes it easier to speak out than it used to be and I'm sure people used to grumble, but who heard them, but their small group of friends? Now, the message can get out the door more broadly.”

This is no doubt something that Apple’s management learned the hard way, as the company’s internal pushback to returning to the office was reportedly organised using the internal Slack messaging platform.

Calling in the unions

One sign that this phenomenon isn’t going away is a growing push for Silicon Valley to unionise. “It wasn't a one-off thing in the sense that everything went back to normal and no one ever thinks about anything like that ever again,��� said the Google insider of their experience of the memo walkout. “There was suddenly [awareness of] a groundswell of dissatisfaction that exists internally and sometimes it bubbles to the outside.”

In fact, in early 2021, a group of around 800 Google employees formally established an Alphabet Workers Union, named for Google’s parent company. The new union “strives to protect Alphabet workers, our global society, and our world”, and the group’s website says that it promotes “solidarity, democracy, and social and economic justice.”

Such an organisation is an unusual move in a Silicon Valley that is so closely associated with libertarian values, but Bellace isn’t surprised. “[Unions] were still viewed as something that was maybe appropriate for the lower paid or the oppressed or goodness knows what. But once you were middle class, and particularly white-collar, you didn't need them. And that I think probably has changed for millennials and ‘Generation Z’; that they realise, wait a moment, we're not capital, we're not in control, our voice as individuals isn't being heard, and therefore group action is necessary.”

Similarly, an entire cottage industry has evolved around whistleblowing, with companies and non-profit organisations providing support and handbooks to make it easier for employees to speak out against their employer. Another unforeseen consequence of the pandemic is that it could accelerate the activist push even more, according to Bellace. “It seems to me that a lot of people have been working remotely from home and this has given them more time to think about their jobs and what they like and don't like,” she said.

Karatzogianni agrees. “What happened in the pandemic is… ten years on the digital battlefield happened in three months, because so many more people had to go online,” she said. “I think the pandemic saw inherent tensions become even stronger.”

Big tech’s internal strife is far from over.

-

Intune flaw pushed Windows 11 upgrades on blocked devices

Intune flaw pushed Windows 11 upgrades on blocked devicesNews Microsoft is working on a solution after Intune upgraded devices contrary to policies

By Nicole Kobie

-

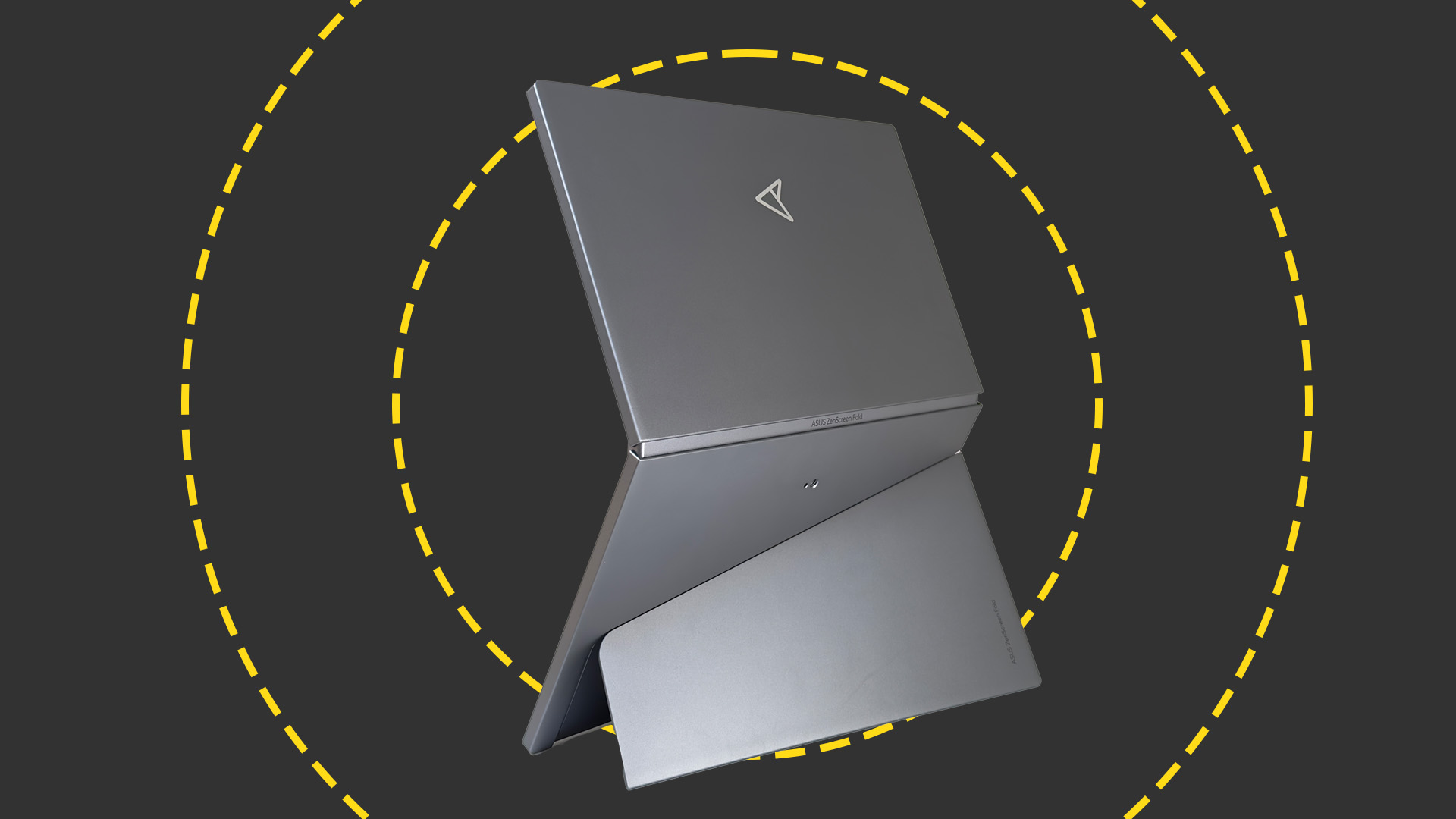

Asus ZenScreen Fold OLED MQ17QH review

Asus ZenScreen Fold OLED MQ17QH reviewReviews A stunning foldable 17.3in OLED display – but it's too expensive to be anything more than a thrilling tech demo

By Sasha Muller

-

How to empower employees to accelerate emissions reduction

How to empower employees to accelerate emissions reductionin depth With ICT accounting for as much as 3% of global carbon emissions, the same as aviation, the industry needs to increase emissions reduction

By Fleur Doidge

-

Worldwide IT spending to grow 4.3% in 2023, with no significant AI impact

Worldwide IT spending to grow 4.3% in 2023, with no significant AI impactNews Spending patterns have changed as companies take an inward focus

By Rory Bathgate

-

Report: Female tech workers disproportionately affected by industry layoffs

Report: Female tech workers disproportionately affected by industry layoffsNews Layoffs continue to strike companies throughout the tech industry, with data showing females in both the UK and US are bearing the brunt of them more so than males

By Ross Kelly

-

How can small businesses cope with inflation?

How can small businesses cope with inflation?Tutorial With high inflation increasing the cost of doing business, how can small businesses weather the storm?

By Sandra Vogel

-

How to deal with inflation while undergoing digital transformation

How to deal with inflation while undergoing digital transformationIn-depth How can organizations stave off inflation while attempting to grow by digitally transforming their businesses?

By Sandra Vogel

-

How businesses can use technology to fight inflation

How businesses can use technology to fight inflationTUTORIAL While technology can’t provide all the answers to fight rising inflation, it can help ease the pain on businesses in the long term

By Sandra Vogel

-

Embattled WANdisco to cut 30% of workforce amid fraud scandal

Embattled WANdisco to cut 30% of workforce amid fraud scandalNews The layoffs follow the shock resignation of the company’s CEO and CFO in early April

By Ross Kelly

-

Some Tech Nation programs could continue after Founders Forum acquisition

Some Tech Nation programs could continue after Founders Forum acquisitionNews The acquisition brings to a close a months-long saga over what the future holds for Tech Nation initiatives

By Ross Kelly