It's been two weeks since CrowdStrike caused a global IT outage – what lessons should we learn?

July's IT outage, caused by a bug in CrowdStrike's Falcon sensor and a Microsoft cloud update, was possibly the largest ever

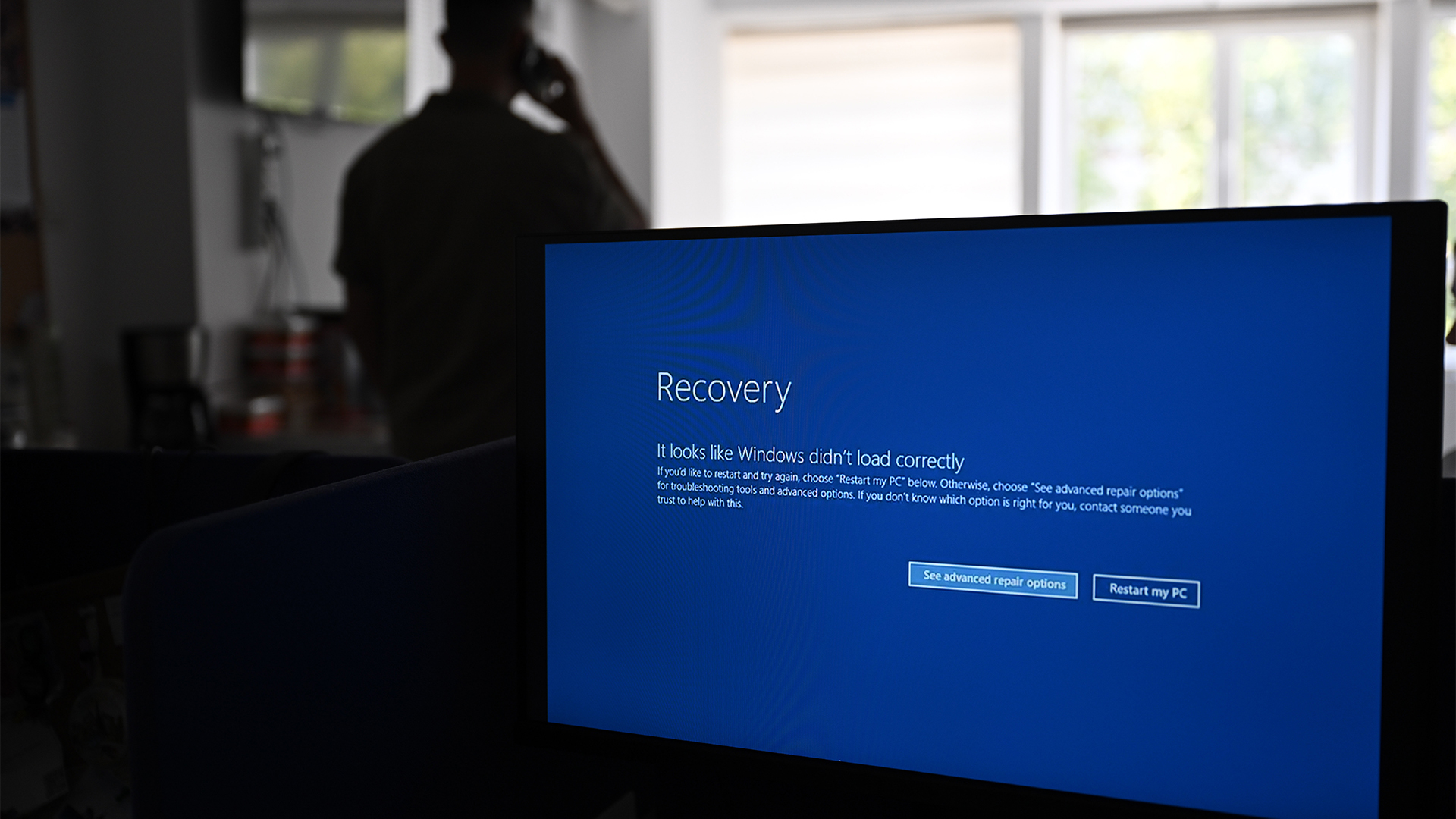

In July, we saw what was possibly the largest ever IT outage to date.

Despite early reports, this was not a cyber attack, but a failure of two separate technologies: CrowdStrike’s Falcon sensor platform and parts of Microsoft’s Azure cloud infrastructure.

It’s one of those unfortunate sets of random coincidences that can turn a mishap from an inconvenience to disaster.

As flights were cancelled and shoppers had to remember how to use cash, it showed just how dependent we are on technology and how much that technology depends on all its moving parts.

Clearly, the outages caused much inconvenience and confusion around the world, and no small amount of embarrassment in IT circles. There were certainly some long days and late nights – and undoubtedly some difficult conversations between CIOs, and their boards.

As yet, it is too early to say how much financial damage resulted from the incidents, and the need to reboot and recover systems, although estimates already run into the billions of dollars.

It’s equally hard to predict the full consequences of the outages.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

In fact, it has proved quite hard to pin down exactly what happened, with claims and counterclaims from across the industry.

According to Paul Stringfellow, CTO at Gardner Systems and a contributing analyst at GigaOm, there were actually two issues that happened over a short period of time.

The first was that Microsoft made some updates to its central US region. These affected Azure and Microsoft 365 services. As Stringfellow points out, these were fixed quickly but still had a global impact.

Then, CrowdStrike issued a “Rapid Response” content update. This was a more minor update than a software patch or upgrade, and the type of thing that security vendors push out frequently – often several times a day.

The update was, apparently, not one that could be delayed. It caused the “blue screens of death” on Windows machines that were all over the news last Friday. The fix, although fairly simple at a technical level, was still disruptive. As the problem affected not just PCs and servers, but equipment such as digital signage, we saw plenty of scenes of chaos at transport hubs across the world.

It could have been worse…

Perhaps surprisingly, though, there are several positives to come out of what happened last week.

Firstly, both Microsoft and CrowdStrike moved quickly to limit the damage. Though the incident no doubt ruined the weekend for plenty of IT professionals, it might have been worse at the start of the working week.

We can also take some reassurance from the fact that this was not a cybersecurity breach. That is probably fortunate: If this much chaos can come from an accident, it’s frightening to think what could happen if someone – say a nation-state backed hacker – set out to cause deliberate disruption, or destruction.

As Forrester analyst Allie Mellen noted on X (formerly Twitter), “infosec doesn’t have a monopoly on the CIA (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) triad or on availability”.

The incident shows how much all organisations, in business and the public sector, depend on their IT. It shows how critical it is that technology is robust, and that organisations have solid recovery plans. This is not the first time a patch or update has caused IT systems to fail and it won’t be the last.

If nothing else, the outages should force CIOs, and boards, to look much harder at their software supply chains.

Lessons for all?

So what have we learned?

Firstly, IT is complex, with numerous interdependencies and it’s not possible to predict every failure, or test every part. There have been some over-simplistic lines coming from parts of the industry, such as “test every patch” or “don’t rely on one vendor”. But that does little to help the CIO on the front line.

“The principles of patch management are clear, in that a single patch can cause huge damage if it is faulty. Over the decades, we’ve seen examples of this so to that extent, nothing has changed,” says Jon Collins, VP of engagement at analysts GigaOm.

“In practice, the scale, breadth and complexity of the challenge is much greater. It would be easy, for example, to say ‘all patches (including security patches) should be tested on a subset of systems before wider rollout,’ but that assumes full understanding of what is installed where, across vast, virtualized estates.”

Sometimes, something will get through. CrowdStrike’s internal QA test, Content Validator, itself had a bug leading it to fail to spot a problem with the content update. It was pushed out widely, and quickly, with the results we have now seen.

Secondly, it’s never a good idea to jump to conclusions. This was not a cyber attack and no doubt some IT teams wasted time thinking that it was. Root cause analysis is never easy, especially under pressure – but it’s vital.

“Understanding the root cause of an incident like this is crucial to take appropriate action to make sure it does not happen again,” says Mellen. “Root cause analysis must be done on both the customer side and the vendor side and will help inform decisions for both parties in the future. For example, canary deployments, where the vendor staggers deployment of an update in batches, would have been very beneficial to identify the issue prior to the major impact of the incident.”

Then there is the fact that availability is the responsibility of the whole business, not just IT (or security). “IT has long held much of the responsibility for identifying and addressing problems related to availability of enterprise systems,” says Mellen.

RELATED WHITEPAPER

But the way an organisation responds to a security incident, or an outage, are not the same. This brings us back to both root cause analysis, a solid – and tested -- incident response plan, and a need to stay calm when everything’s going wrong.

“In this debacle, there seems to be an unnecessary amount of rhetoric about, ‘Oh my goodness, we’ve found ourselves subject to unexpected disaster’,” says Collins.

“But talk to any security professional or indeed, operations leader, and they will have been completely unsurprised by what happened here. In other words, we’ve learned that we’re still in denial about the fallibility of technology, at the highest levels of some of our biggest organisations.”

Accepting that fallibility means we will be better prepared for the next time.

-

Can enterprises transform through startup theory?

Can enterprises transform through startup theory?In-depth For big corporations, the flexibility, adaptability, and speed of a startup or scale-up is often the total opposite of what’s possible within their own operations

-

AI is creating more software flaws – and they're getting worse

AI is creating more software flaws – and they're getting worseNews A CodeRabbit study compared pull requests with AI and without, finding AI is fast but highly error prone

-

Game-changing data security in seconds

Game-changing data security in secondswhitepaper Lepide’s real-time in-browser demo

-

Unlocking the opportunities of open banking and beyond

Unlocking the opportunities of open banking and beyondwhitepaper The state of play, the direction of travel, and best practices from around the world

-

Accelerated, gen AI powered mainframe app modernization with IBM watsonx code assistant for Z

Accelerated, gen AI powered mainframe app modernization with IBM watsonx code assistant for Zwhitepaper Many top enterprises run workloads on IBM Z

-

Magic quadrant for finance and accounting business process outsourcing 2024

Magic quadrant for finance and accounting business process outsourcing 2024whitepaper Evaluate BPO providers’ ability to reduce costs

-

The power of AI & automation: Productivity and agility

The power of AI & automation: Productivity and agilitywhitepaper To perform at its peak, automation requires incessant data from across the organization and partner ecosystem.

-

Let’s rethink the recruiting process

Let’s rethink the recruiting processwhitepaper If you designed your recruiting process for a new company, what would you automate to attract and hire the best talent?

-

AI academy: Put AI to work for customer service

AI academy: Put AI to work for customer servicewhitepaper Why AI is essential to transforming customer service

-

How can small businesses cope with inflation?

How can small businesses cope with inflation?Tutorial With high inflation increasing the cost of doing business, how can small businesses weather the storm?