What cracking open the App Store means for the future of iOS

Fears begin to mount over whether the EU's Digital Markets Act (DMA) will backfire

When you buy an Apple product, it can often feel like making a deal with the devil. On the one hand, you can be confident your new device will be slick, intuitive, and powerful. But on the other, you’re acquiescing to Apple’s locked-down ecosystem of apps and services. Want to run an unapproved app on your new iPhone? Forget it.

This is how it’s been since 2008 when the App Store first launched. Since then, apps have turned into an almost unfathomably lucrative business for Apple. In the year prior to Apple’s most recent financial statement, the store raked in a staggering $78 billion of services revenue, most of which is derived from the App Store.

If rumors are true, though, the gold rush could soon be coming to an end. According to well-connected business journalist Mark Gurman of Bloomberg News, developers are hard at work updating iOS so it can support third-party app stores and apps that have been “side-loaded” onto the device. Such a move would dramatically upend years of Apple’s uncompromising policy – and shake the foundations of the iPhone’s security model, too.

The Digital Markets Act (DMA) spells trouble for big tech

The EU’s Digital Markets Act (DMA) was signed into law in September last year. This sprawling piece of legislation had been crafted with only one goal in mind.

RELATED RESOURCE

“We've gone through several decades where a lot of these companies have been allowed to kind of grow globally unchecked,” says professor Vince Manzerolle, who studies the political economy of digital media at the University of Windsor in Canada. “This legislation is almost crafted to take down some of these big companies.”

When the DMA comes into force, many expect it’ll require Apple to allow third-party app stores on its devices. “If Apple is actually forced to comply with the letter of this new kind of legislation it will, I think, transform its operations in some fairly profound ways,” says Manzerolle. “Allowing sideloading and third-party app stores is a pretty significant change.”

One major point of contention between Apple and the EU is the 30% fee Apple charges for every transaction in the App Store – and most in-app purchases too. “I think the EU is just interested in lower prices and allowing more competition,” says Dr Kathryn McMahon, associate professor of competition law at Warwick University. “They say the 30% is an excessive fee. It's in no way related to the cost. It's also discriminatory because it's not charged across the board.”

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Scrapping the ‘Apple Tax’

The fee – often referred to as the 'Apple Tax' – has long been unpopular with developers, as Apple imposes draconian rules on how apps can take payments. Under the current rules, all in-app purchases of digital goods must use Apple's own payment system.

Apple vs Epic Games

The 'Apple Tax' row escalated in August 2020, when Fortnite developers Epic Games built a version of the game that used its own payment system. Apple called Epic’s bluff, and as a result, Fortnite wasn't available on iPhone or iPad until the lawsuit was settled this year. With the DMA, though, the EU has taken Epic’s side. Under the new model, Epic could get the game onto iPhones by using its own Epic Games store.

Apps aren’t even allowed to signpost alternative payment methods, such as by linking users to a website. It means that, for example, you can download the Netflix app and log in – but if you want to sign up for a new account, you'll need to figure out how to do it yourself because the company doesn’t want to give Apple a cut of its revenue.

The option to use alternative app stores could be of huge benefit to developers across the board. “There are lots of rules and restrictions on what you can and can't do,” says Dr Greig Paul, an electrical engineer and security researcher at Strathclyde University. “You're playing in someone else's walled garden, so to speak.”

“If you give people the option to build apps [without approval], who knows what we will see?” he adds, arguing that it could ultimately be good for innovation if iPhone users could use a different way to download a web browser that hasn’t been forced to use Apple’s own web rendering engine, for example. “You might get the Firefox browser, using Firefox's engine on an iPhone, and that might push Safari to up its performance, or it might give you more extensions.”

Unpicking the iOS security concerns

Cracking open Apple’s app store monopoly could be good news for consumers, who would have more choice and control over the apps on their phones. But there could also be unintended consequences for iOS security.

“If you've been selling people on 'you don't need to think about security, you don't need to think about privacy', and then all of a sudden there are new [threats], maybe users are not prepared for that,” says Manzerolle. “I certainly think that's a possibility.”

Allowing other app stores or sideloading would put iOS policies broadly in line with Android, which has always been more open and flexible than Apple’s super-locked down operating system, but also more open to attack. “You're adding more complexity as you're opening up the platform,” said Manzerolle. “And there's all sorts of smart hackers and cyber criminals out there. They're probably looking for an opportunity to get into the Apple ecosystem and exploit people's trust in the platform.”

Will the EU’s measures backfire?

Of course, even if Apple does bend to the EU’s will, and alternative app stores do emerge on iOS, it doesn’t necessarily mean that consumers will follow. McMahon wonders if the EU could find itself in a similar position to the one it found itself in 2005 when it tried to rein in Microsoft’s ability to use Windows to push its own media playback software to consumers.

“Microsoft, as a result of the EU case, had to ship Windows without Windows Media Player,” says McMahon, who explains that when Microsoft later released a new version of Windows XP without Media Player alongside the bundled version, it died a lonely death.

“Nobody bought it. Nobody wanted to get it separately,” says McMahon. “The whole point of the antitrust case was to separate it out to allow much more competition in music browsers and streaming, but it didn't really have that effect. Because people just preferred [the bundle] and they just purchased the entire package.”

Will history repeat itself for iOS? Or will this be the beginning of a dramatic new era for the iPhone? If the rumors are true, we’re about to find out.

-

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?AI PCs are fast becoming a business staple and a surefire way to future-proof your business

By Bobby Hellard

-

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiatives

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiativesNews Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI have announced the launch of two new channel growth initiatives focused on the managed security service provider (MSSP) space and AWS Marketplace.

By Daniel Todd

-

‘Europe could do it, but it's chosen not to do it’: Eric Schmidt thinks EU regulation will stifle AI innovation – but Britain has a huge opportunity

‘Europe could do it, but it's chosen not to do it’: Eric Schmidt thinks EU regulation will stifle AI innovation – but Britain has a huge opportunityNews Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt believes EU AI regulation is hampering innovation in the region and placing enterprises at a disadvantage.

By Ross Kelly

-

The EU just shelved its AI liability directive

The EU just shelved its AI liability directiveNews The European Commission has scrapped plans to introduce the AI Liability Directive aimed at protecting consumers from harmful AI systems.

By Ross Kelly

-

A big enforcement deadline for the EU AI Act just passed – here's what you need to know

A big enforcement deadline for the EU AI Act just passed – here's what you need to knowNews The first set of compliance deadlines for the EU AI Act passed on the 2nd of February, and enterprises are urged to ramp up preparations for future deadlines.

By George Fitzmaurice

-

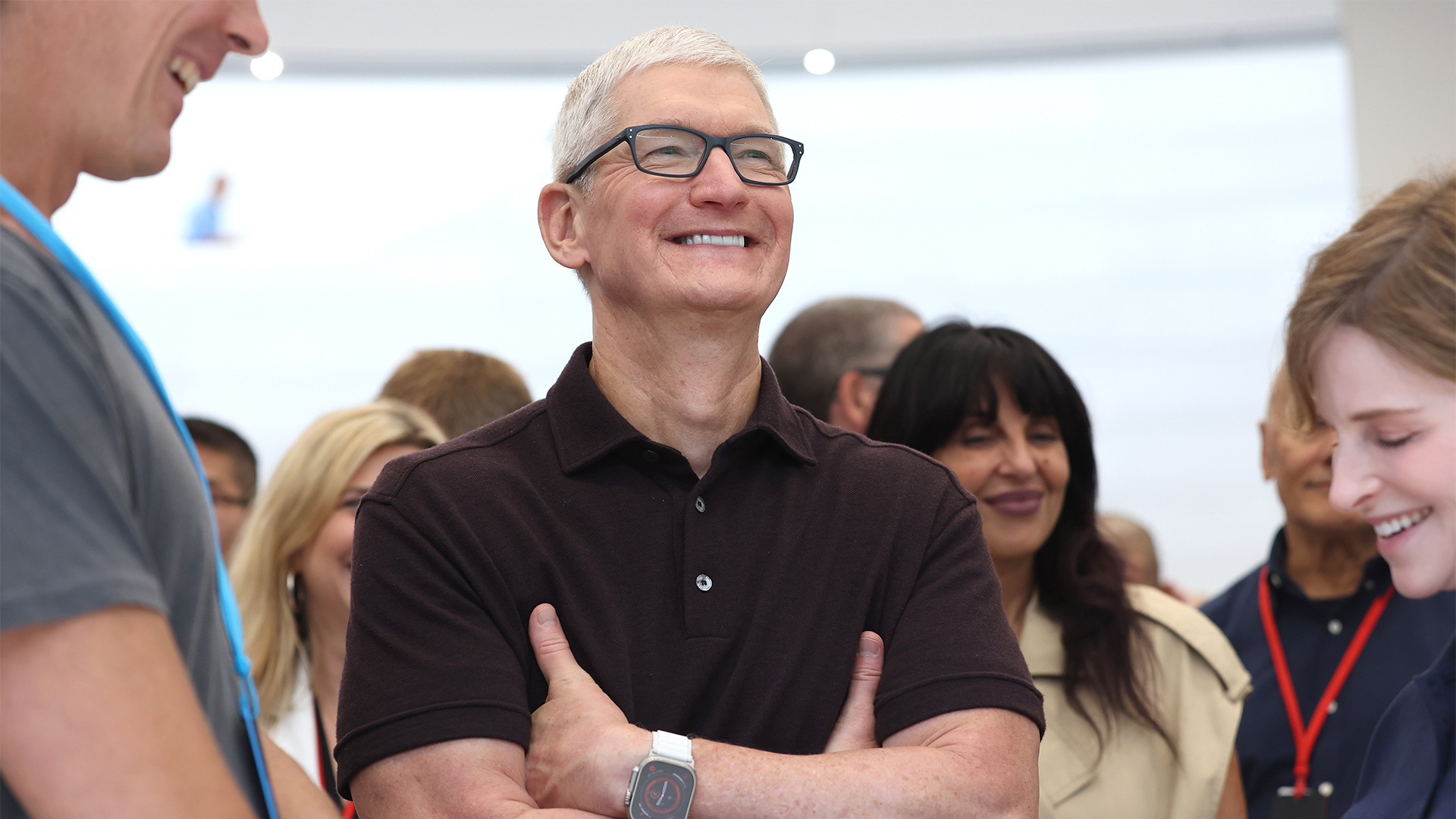

Apple CEO Tim Cook hails company's "deep connection" with UK as figures show it's invested £18 billion since 2019

Apple CEO Tim Cook hails company's "deep connection" with UK as figures show it's invested £18 billion since 2019News Apple has invested upwards on £18 billion in the UK and doubled its engineering headcount since 2019.

By Emma Woollacott

-

EU agrees amendments to Cyber Solidarity Act in bid to create ‘cyber shield’ for member states

EU agrees amendments to Cyber Solidarity Act in bid to create ‘cyber shield’ for member statesNews The EU’s Cyber Solidarity Act will provide new mechanisms for authorities to bolster union-wide security practices

By Emma Woollacott

-

The EU's 'long-arm' regulatory approach could create frosty US environment for European tech firms

The EU's 'long-arm' regulatory approach could create frosty US environment for European tech firmsAnalysis US tech firms are throwing their toys out of the pram over the EU’s Digital Markets Act, but will this come back to bite European companies?

By Solomon Klappholz

-

EU AI Act risks collapse if consensus not reached, experts warn

EU AI Act risks collapse if consensus not reached, experts warnAnalysis Industry stakeholders have warned the EU AI Act could stifle innovation ahead of a crunch decision

By Ross Kelly

-

Three quarters of UK firms unprepared for NIS2 regulations, study finds

Three quarters of UK firms unprepared for NIS2 regulations, study findsNews Senior management can be held personally liable for non-compliance under NIS2 rules

By Ross Kelly