What is Section 230 and why does it matter?

Revoking the law could have unpredictable and far-reaching consequences

They’ve been called “the twenty-six words that created the internet.”

The 26 words in question are Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act. If that sounds boring, just know that in IT, it’s the hottest of hot-button political issues.

Section 230 is the epicenter of a high-stakes political and cultural battle that’s brewing between Silicon Valley and Washington, D.C.

It’s an ongoing tug-of-war that could potentially change how we all use social media — and whether social media can even continue to exist in its current form.

Section 230 has become an increasingly popular target in D.C., where President Donald Trump tried to kill it outright, President Joe Biden wants to rewrite it, Congress keeps threatening to repeal it, and Big Tech CEOs keep showing up to defend it.

Here’s everything you need to know about this obscure but increasingly important law.

What is Section 230?

Section 230 is a provision within the 1996 Communications Decency Act, which was Congress’s first attempt to regulate pornography on the internet.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

When it became law 25 years ago, Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube didn’t exist. But as written, Section 230 prevents an “interactive computer service” from being treated as the publisher of third-party content. Essentially, it says websites can’t be held legally liable for any content that’s posted by third parties — with a few exceptions such as sex trafficking or copyright violations.

Over the past quarter-century, this has been interpreted as a handy get-out clause for social media companies, as it prevents them from being held responsible for anything their users post.

Legally speaking, it means anyone is free to post whatever blatant misinformation they want online, and the owners of the website they post it on can’t be sued or prosecuted over it.

This has worked out especially well for social media giants like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, which run on vast, churning quantities of user-generated content without any fear of legal repercussions.

Essential to the internet

Here are the 26 words that created the internet as we know it today: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.”

The law was passed at a time when internet usage was just starting to blow up. It was 1996, right when everything was about to change.

Section 230 is often singled out as being essential to the growth of the internet. Before it became law, early online forums could be held legally responsible for anything posted on them. But doing things that way wouldn’t have scaled to meet today’s needs, social media companies say.

So Section 230’s protections, and those of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, are credited for helping to foster the creation of social media, video streaming, and search engines — among other developments.

Attempts to abolish it

Getting rid of Section 230 would probably have unpredictable and far-reaching effects, but some elected leaders want to do it anyway.

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle have discussed revoking Section 230, although they give different reasons for doing so. Republicans aim to combat perceived anti-conservative bias, while Democrats are interested in holding companies liable for dangerous misinformation.

Last year, then-President Donald Trump issued an executive order attempting to strike down Section 230 because Twitter had flagged some of his tweets about mail-in ballots. Because Section 230 gives social media sites the right to regulate content on their platforms, Trump and other Republicans accuse tech firms of using Section 230 as a shield to cover for a leftist agenda.

Meanwhile, Congressional lawmakers have repeatedly introduced legislation targeting Section 230.

In June 2020, senators revealed the bipartisan Platform Accountability and Consumer Transparency (PACT) Act that would’ve held social media companies liable for hosting illegal content. Republican senators also introduced the Online Freedom and Viewpoint Diversity Act in September 2020 that would have held social media companies liable for third-party content.

The bipartisan PACT Act was introduced in June 2020 by US Senators Brian Schatz (D-HI) and John Thune (R-SD). It has not been passed into law at this point.

The proposed law aims to strengthen the transparency of social media platforms’ content moderation policies while holding companies accountable for illegal content and content posted that violates their own policies.

With Section 230 coming under severe scrutiny, PACT aims to create more transparency by requiring social media platforms to explain their content moderation practices in a way that’s easily accessible to the platform’s users.

PACT would also require companies to develop a complaint system to notify its users of moderation decisions within 14 days. Companies would have to establish appeals processes for content moderation decisions too.

Further, PACT would amend Section 230 by requiring online platforms to remove user-posted content a court deemed illegal within 24 hours of the court’s decision. PACT would also prevent online platforms from using Section 230 as a defense if federal regulators pursue civil actions related to online activity.

“Section 230 was created to help jumpstart the internet economy, while giving internet companies the responsibility to set and enforce reasonable rules on content,” Sen. Schatz said. “But today, it has become clear that some companies have not taken that responsibility seriously enough.”

Biden is a critic too

President Joe Biden has also expressed interest in abolishing the law.

Shortly before Biden’s inauguration, a senior technology advisor signaled that the Biden administration is interested in changing Section 230. Bruce Reed, who also advised Biden on technology during his vice presidency, announced during the online launch of a book in which he co-wrote a chapter on Section 230.

“I think there’s a well-emerging consensus that it’s long past time to hold the big social media platforms accountable for what’s on their platforms the way we do newspaper publishers and broadcasters,” Reed said.

Biden has long been a critic of Big Tech, telling the New York Times in 2020 that he has “never been a big Zuckerberg fan.” “[The Times] can't write something you know to be false and be exempt from being sued. But he can,” he said in the interview. Biden added, “Section 230 should be revoked, immediately should be revoked, number one.”

Big Tech Execs Play Defense

For their part, Big Tech executives argue that changing Section 230 could chill freedom of speech online. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey testified in a congressional hearing that revoking Section 230 would force online platforms to preemptively take down far more content for fear of being sued.

Congressional leaders grilled Big Tech CEOs about Section 230 and misinformation at a hearing in March 2021.

“My primary goal would be to help update Section 230 to reflect the modern reality and what we’ve learned over 25 years. I do think that it plays a foundational role in the Internet,” Zuckerberg testified.

He said he was committed to reforming the law: “230 broadly is important so I wouldn't repeal the whole thing,” he said.

Zuckerberg advocated for three changes to the law’s implementation. First, he called for platforms to report how much harmful content they find. Second, he said platforms should be held accountable for their material. Finally, he warned that while these policies need to apply to large platforms, they should exclude smaller ones.

It remains to be seen what will happen to Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act. A full 25 years after Congress passed into law, it has survived numerous legal challenges, and many experts credit it with helping the internet flourish.

We’ll see if “the twenty-six words that created the internet” will survive — or what, if anything, will replace them.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

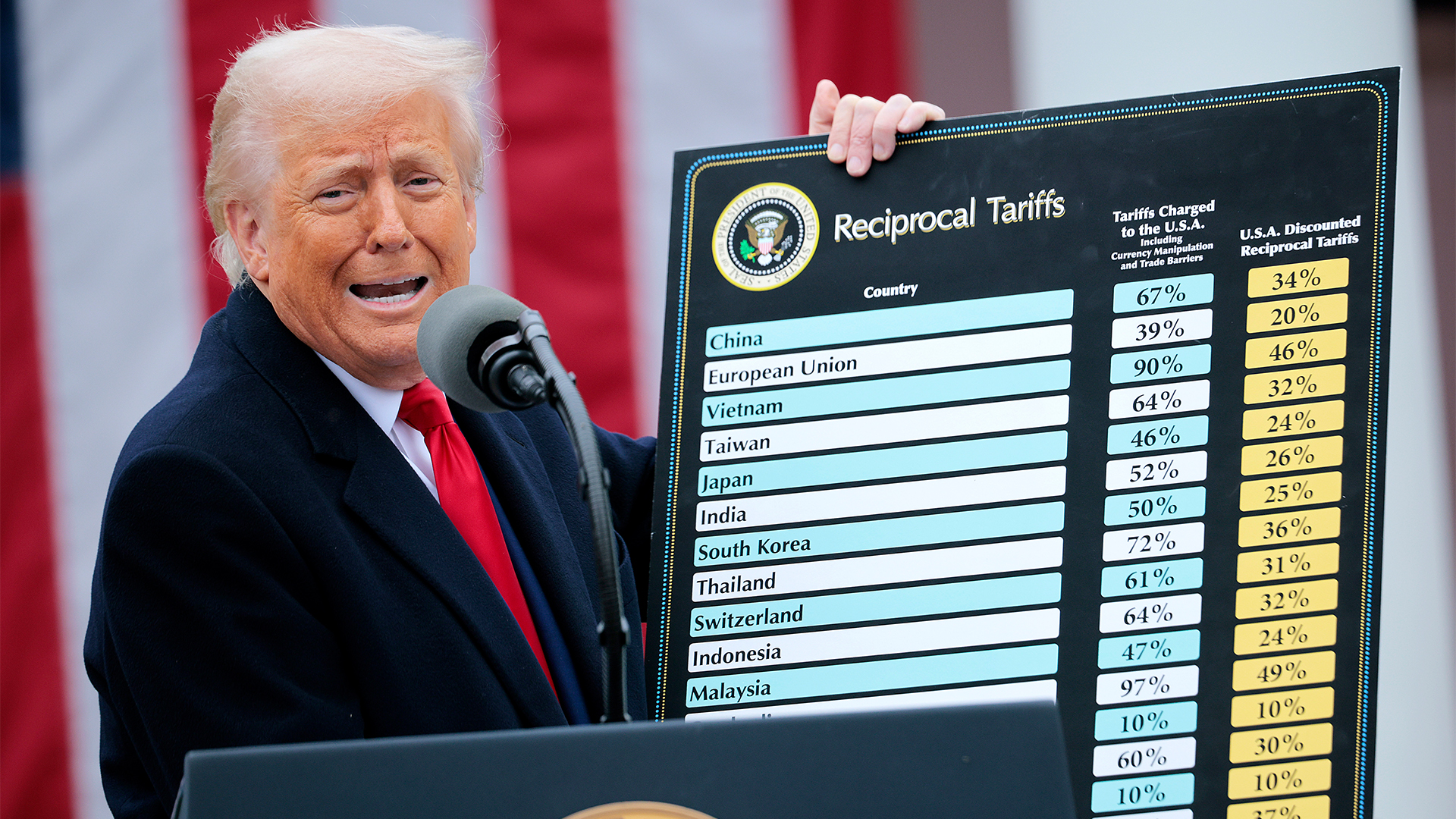

IDC warns US tariffs will impact tech sector spending

IDC warns US tariffs will impact tech sector spendingNews IDC has warned that the US government's sweeping tariffs could cut global IT spending in half over the next six months.

By Bobby Hellard Published

-

US government urged to overhaul outdated technology

US government urged to overhaul outdated technologyNews A review from the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) has found legacy technology and outdated IT systems are negatively impacting efficiency.

By George Fitzmaurice Published

-

US proposes new ‘know-your-customer’ restrictions on cloud providers

US proposes new ‘know-your-customer’ restrictions on cloud providersNews The US aims to stifle Chinese AI competition with new restrictions on cloud providers to verify foreign data center users

By Solomon Klappholz Published

-

SEC passes rules compelling US public companies to report data breaches within four days

SEC passes rules compelling US public companies to report data breaches within four daysNews Foreign entities trading publicly in the US will also be held to comparative standards

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

US says National Cybersecurity Strategy will focus on market resilience and private partnerships

US says National Cybersecurity Strategy will focus on market resilience and private partnershipsNews The recently announced implementation plans alow for more aggressive action against ransomware gangs

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

US ‘Tech Hubs’ drive aims to boost innovation in American heartlands

US ‘Tech Hubs’ drive aims to boost innovation in American heartlandsNews The development of the hubs will could help drive regional innovation and support for tech companies

By Ross Kelly Published

-

Biden sets June deadline for $42 billion broadband funding outline

Biden sets June deadline for $42 billion broadband funding outlineNews The announced deadline come prior to a much-awaited update to the FCC's US broadband map, giving a clearer image of the internet challenges facing the nation

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

FCC eyes formal ban of all Huawei, ZTE equipment sales

FCC eyes formal ban of all Huawei, ZTE equipment salesNews Approaching the deadline to pass such a ruling, companies such as Kaspersky face similar restrictions

By Rory Bathgate Published