Microsoft allegedly fired whistleblower for exposing company corruption

The whistleblower estimates that a minimum of $200 million each year goes to Microsoft employees, partners, and government employees

A whistleblower has claimed that he was fired by Microsoft after bringing attention to bribes that were being conducted at the company.

Yasser Elabd, the whistleblower, was recruited at Microsoft in 1998 and helped distribute the company’s products through the Middle East and Africa, he said in an essay posted on Lioness on Friday.

In the region, Microsoft utilised a network of partners called Licensing Solution Partners, who are authorised to engage with large public customers as they possess technical and business competencies, said Elabd. Through these partners, Microsoft brings e-health solutions to hospitals and digitised services to government agencies. The partner then takes a share of Microsoft’s licensing sales revenue, usually around 10-15%.

Elabd said that one way Microsoft closes deals using these partners is to create a business investment fund to pay for training or pilot projects that could cement longer-term deals. As the director of public sector and emerging markets for the Middle East and Africa, Elabd said he had oversight of the requests for these funds.

What is the whistleblower alleging?

The whistleblower recounted how in 2016, a $40,000 request came through to accelerate the closing of a deal in one African country. However, he felt something was wrong as the customer didn’t appear in Microsoft’s internal database of potential clients, and the partner involved was under-qualified for the project. Additionally, the partner wasn’t meant to be doing business with Microsoft as he had been terminated four months earlier for poor performance on the sales team, and corporate policy doesn’t allow former employees to work as partners for six months from their departure.

Elabd brought these issues up and escalated them to his manager, HR, and legal departments. The legal and HR teams put a stop to the $40,000 spend but, to Elabd’s surprise, didn’t look deeper into the Microsoft employees who were orchestrating the fake deal.

However, the manager of the employee who had submitted the request sought Elabd out, angry at what he had done. Soon after, Elabd said that this manager was promoted and scheduled a one-on-one meeting, where he said their job was to bring as much revenue as they could to Microsoft.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

“He added, ‘I don’t want you to be a blocker. If any of the subsidiaries in the Middle East or Africa are doing something, you have to turn your head and leave it as is. If anything happens, they will pay the price, not you,’” stated Elabd, responding that he wouldn’t block anything unless it violated company policy, which angered the manager.

Elabd decided to request a meeting with his boss, a VP, who, after meeting him, suggested the three of them should meet, which never occurred. Deciding to escalate this again, Elabd emailed Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella and a HR executive to explain he felt mistreated by the manager. The VP got in touch again and said he had essentially booked a one-way ticket out of Microsoft for escalating the matter to Nadella.

Microsoft put Elabd on a performance improvement plan which, when he refused to acknowledge the plan, culminated in the company ending his employment in June 2018.

What were the examples the whistleblower mentioned?

Elabd said that in 2020, a clearer picture emerged of why executives had wanted to shut down his line of questioning.

“A former colleague based in Saudi Arabia who had become upset by what he saw taking place at Microsoft began forwarding me emails and documentation—and I learned that the corruption went much deeper than I had suspected,” he stated.

While examining a PwC audit, Elabd discovered that when agreeing to terms of sale for a product or contract, a Microsoft executive or salesperson would propose a side agreement with the partner and the decision maker at the entity making the purchase. The decision maker on the customer side would ask Microsoft for a discount, which would be granted, but the end customer would pay the full fee anyway. The amount of the discount would then be distributed among the Microsoft employee, or employees, involved in the scheme, the partner, and the decision maker at the purchasing entity, often a government official, he alleges.

In three of seven sampled transactions, discounts worth over $5.5 million weren’t passed through to end customers, in this case, two government-controlled entities, said Elabd. Another audit report showed a deal with the Saudi Ministry of the Interior in which a $13.6 million discount didn’t pass through. Other audits of deals in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia found a total of $20 million accounted for.

“Were an audit conducted for all of the partners using these practices, I believe the sums of money found to be stolen would be enormous. Where did these millions of dollars go?” wrote Elabd.

Auditors also discovered that Qatar’s Ministry of Education was paying $9.5 million annually over seven years for Microsoft Office and Windows licences it wasn’t using, as it didn’t have any PCs or laptop computers. Elabd added there was a similar scheme in Cameroon, where neither the government nor Microsoft could confirm whether 500,000 Microsoft Office Academy 354 licences were actually in use.

RELATED RESOURCE

The new normal: The future role of finance

The changing role of the finance function during business disruption

In Saudi Arabia, when the Ministry of Health uncovered a $1.5 million payment for Skype licences that were never provided, it demanded that 10,000 licences be delivered within 72 hours or he would conduct an audit. Elabd underlined that the money would have already been distributed among those involved in the scam. Microsoft immediately provided new licences before the side agreements could be exposed.

Elabd said another common practice revolved around creating fake purchase orders. In 2017, it was suspected that one sales manager forged the signature of the Saudi National Guard’s deputy minister on a fake Microsoft order.

“I have evidence that people on Microsoft’s legal, HR, and finance teams—as well as officials from the region’s public sector—knew about this forgery,” said Elabd. “When the matter was investigated, the sales manager threatened to speak out about the widespread corruption he had seen at the company. I heard that Microsoft paid him to leave quickly and quietly, took no legal action against him, and did not report the forgery.”

Were there other whistleblowers?

Elabd said he isn’t the only person at Microsoft who has alleged corrupt practices. He knows of five others from various departments who were terminated or pushed to resign for raising flags about inconsistencies in finances.

One whistleblower filed an anonymous complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) alleging the South African Department of Defense overpaid Microsoft partner EOH Mthombo for software licences. The complaint states that the deal, in which EOH received $8.4 million, was flagged to a Microsoft compliance officer but no action was taken by the company. The whistleblower contends this was because EOH was helping the tech giant with a $50 million contract with the South African Police Service.

In Elabd’s estimation, a minimum of $200 million each year goes to Microsoft employees, partners, and government employees. He believes around 60-70% of the company’s salespeople and managers in the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Europe are receiving these payments. Among the customers who he believes have received the money are government officials in Ghana, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia.

Elabd pointed to Microsoft paying a penalty to the US government of $25.3 million in 2019 for allowing bribery and kickbacks in Hungary, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and Turkey. One term in the settlement with the DOJ was to terminate a contract with a specific partner. Elabd said that although Microsoft formally terminated the contract, it’s still working with the partner through a third-party company.

Elabd underlined he submitted his evidence to the SEC and Department of Justice three times but they didn’t take up the case, claiming that the pandemic has prevented them from gathering more evidence from abroad. He added that he provided documentation to the agencies that he believes show Microsoft is in breach of a 2019 agreement and is still participating in corrupt business practices in direct violation of US law.

“Microsoft is allowing employees to steal from its own pockets and from the governments of the countries it operates in to help cement its monopoly on the continent,” said Elabd. “As the manager told me all those years ago, all that matters is that Microsoft earns as much money as possible. Employees who break the law in service of this goal are living lavish lifestyles, while those who speak up are ostracised and pushed out.”

Elabd added that by declining to investigate these allegations, the SEC and DOJ have given Microsoft the green light.

What is Microsoft’s response?

“We are committed to doing business in a responsible way and always encourage anyone to report anything they see that may violate the law, our policies, or our ethical standards,” Becky Lenaburg, vice president and deputy general counsel of Compliance & Ethics at Microsoft told IT Pro. “We believe we’ve previously investigated these allegations, which are many years old, and addressed them. We cooperated with government agencies to resolve any concerns.”

Microsoft said it has taken action to terminate employees and partnerships as part of its investigations. It added that it has a mandatory standards of business conduct course that every employee is required to take, which covers issues like these and coaches employees on ways to report concerns.

"The SEC does not comment on the existence or nonexistence of a possible investigation," an SEC spokesperson told IT Pro.

Zach Marzouk is a former ITPro, CloudPro, and ChannelPro staff writer, covering topics like security, privacy, worker rights, and startups, primarily in the Asia Pacific and the US regions. Zach joined ITPro in 2017 where he was introduced to the world of B2B technology as a junior staff writer, before he returned to Argentina in 2018, working in communications and as a copywriter. In 2021, he made his way back to ITPro as a staff writer during the pandemic, before joining the world of freelance in 2022.

-

Why keeping track of AI assistants can be a tricky business

Why keeping track of AI assistants can be a tricky businessColumn Making the most of AI assistants means understanding what they can do – and what the workforce wants from them

By Stephen Pritchard

-

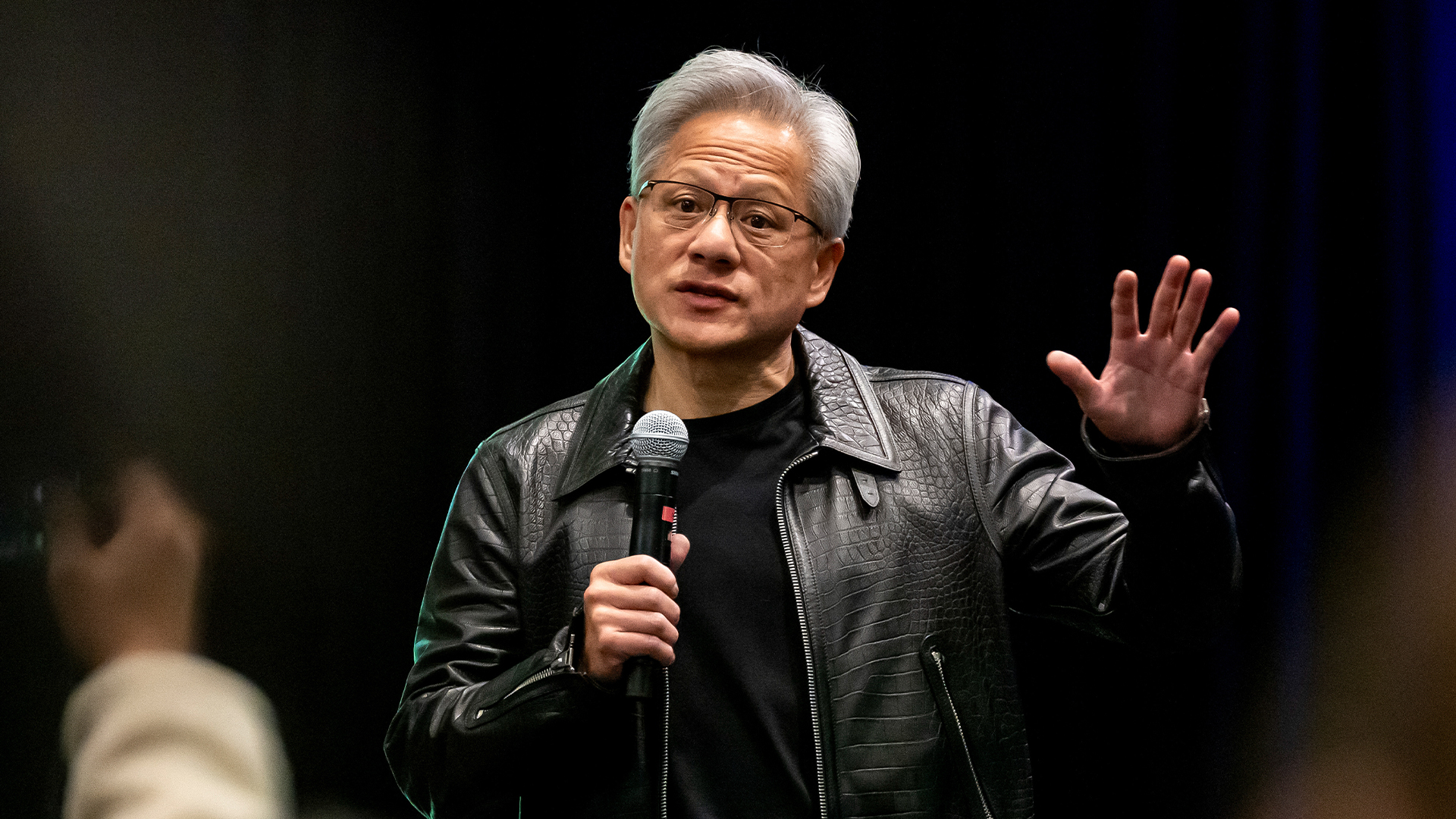

Nvidia braces for a $5.5 billion hit as tariffs reach the semiconductor industry

Nvidia braces for a $5.5 billion hit as tariffs reach the semiconductor industryNews The chipmaker says its H20 chips need a special license as its share price plummets

By Bobby Hellard