Why the UK is dragging its feet on regulating big tech

Britain’s delay to empowering the Digital Markets Unit (DMU) with the powers it craves could see the once-frontrunner fall behind the rest of the world

The UK government’s regulatory pursuit of big tech companies has stalled once again, and the country is now at risk of lagging behind the rest of the world when it comes to setting the agenda, critics are warning.

Britain has contemplated imposing stronger regulations on the digital sector for years, especially in order to promote greater competition and innovation. After years of rhetoric, the government finally proposed the Digital Markets Unit (DMU) – a new arm of the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) – in November 2020.

Nearly two years on and several re-announcements later, most recently in May, we’re no closer to seeing the unit get the statutory powers it needs to be an effective force. This is despite the fact it was established last year. The omission of any relevant legislation from the Queen’s Speech means these powers now won’t be granted for at least another year. Without it, the regulator won’t be able to set any statutory rules for the biggest tech firms, nor impose fines if they violate those rules.

UK plan to abandon big tech regulator powers “makes no sense”

Many have been quick to warn this delay will result in significant consequences for UK businesses and consumers. Others, meanwhile, warn it can make it difficult to unleash the full potential of the UK’s most exciting startups if tech giants’ swelling market power continues to create barriers to entry for entrepreneurs.

"The news that the government isn't intending to strengthen the work of the CMA makes no sense,” Heather Burns, head of policy and governance at the privacy-focused network Maidsafe, tells IT Pro. “In failing to strengthen the CMA's work while simultaneously pressing forward with the Online Safety Bill, the government is doing nothing to address the biggest problems at the point of their biggest impact, on one hand, while creating a hell of a lot of new problems for everyone else on the other hand.”

While the DMU currently exists with around 60 members of staff, it has no powers beyond the CMA's existing capabilities. Yet, big tech’s dominance is ever-growing; the COVID-19 pandemic has brought a significant increase in both profits and power, which has led to calls for the stronger policing of these entities.

While authorities on a global scale are reacting to these calls – Europe has reached an agreement on landmark digital rules to rein in online “gatekeepers”, and the US has a package of tech-focused antitrust bills – why is the UK dragging its feet?

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Why is Britain so slow to act?

There are likely to be a number of factors behind the government’s change of pace over big tech regulation, including the impact of COVID-19 while there’s no doubt Brexit is squeezing parliamentary bandwidth. That these proposals have effectively been put on the back burner also reflects the fact the government doesn’t see them to be as urgent as the CMA does, according to Peter Broadhurst, a partner at law firm Crowell & Moring.

“It may be that the government is actively slowing the process down in order to leave more time to reflect, consider and consult on what is the right balance between the need – and the cries – to control big tech companies, and a desire to signal that the UK is still a tech and innovation-friendly country,” he tells IT Pro. “The government wants to get that balance right because it wants the UK to be a winner in the competition for attracting tech investment.

“Indeed, the government may think that tech companies will view the delay in launching any specific new laws as a window of opportunity to establish or grow their business in post-Brexit Britain.”

This latter point is one shared by Colin Hayhurst, CEO of Mojeek, a UK-based search engine with a no tracking privacy policy, who believes the government’s stalling could be part of a ploy to attract big tech companies to the country.

"Currently, US big tech EMEA HQs are in Ireland and Luxembourg,” he tells IT Pro. “A big prize for the UK would be attracting Google, Meta, Amazon, Apple, or Microsoft to move their EMEA headquarters to London, where they all have a substantial presence. With Brexit freedoms to reduce regulatory and tax burdens for these companies, perhaps delaying big tech regulation helps to further that aim.

“Meanwhile, the EU will be increasingly seen as hostile to big tech, as they get ahead of the UK with their Digital Markets Act (DMA) and Digital Services Act (DSA).

Another reason for the delay could be that the UK government is biding its time to observe how the EU’s regulations play out. Jean-Philippe Vergne, associate professor of Strategy at the UCL School of Management, tells IT Pro: “One might assume that a Conservative government naturally shies away from regulating the economy further, but a ‘wait and see’ approach has two upsides. First, to distinguish the UK from the rest of the EU, which some might see as a plus. Second, to learn from potential shortcomings of the new EU regulations.”

Does the UK risk falling behind the rest of the world?

The UK was once considered a leader in the growing movement to crack down on big tech dominance. The CMA, for example, was one of the pioneers of regulation, and one of the first competition authorities around the world to start scrutinising the activities of tech companies more closely.

That increase in scrutiny by the CMA, which adopted the view that technology was no longer invariably good for competition and consumers, had a wide-reaching knock-on effect. It arguably brought us to the situation we have today, in which most major antitrust jurisdictions are reviewing their rules and concluding not enough has been done to regulate the business practices of massive tech companies.

While once at the forefront, however, the delay in empowering the DMU means the UK will inevitably be left in the background, according to Broadhurst. “Despite the comments from the CMA that they understand the reasons for the delay, and that this isn’t a big blow, it will obviously be frustrating for them,” he says.

Will Richmond-Coggan, a tech and privacy specialist at Freeths LLP, agrees the UK’s current position could see it become vulnerable. He adds that despite the country’s wishes to set its own post-Brexit agenda, including the new data protection framework in the form of the Data Reform Bill, this situation could force it to rely more heavily on EU legislation.

“The UK can ill-afford for another jurisdiction’s legislation to set the gold standard for big tech regulation in the way that the EU has done with GDPR in relation to personal data,” he tells IT Pro. “In those circumstances, we would be likely to be increasingly reliant on mirroring those rules or finding ourselves entirely out of step with the global tech regulatory landscape.”

What’s next for the DMU?

It remains unclear when powers for the DMU will be legislated, and a spokesperson for the Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) tells IT Pro it “cannot comment on timelines”. They insist the pro-competition regime will change the conduct of the most powerful tech firms, and that the department will respond to its consultation “shortly”.

This means, for the foreseeable future, at least, big tech firms could be in for a bumpy ride, particularly when it comes to regulatory hurdles surrounding mergers and acquisitions, through to delays or price impacts when looking to sell to buyers from other territories.

Broadhurst, however, believes the CMA is well within its rights to flex its muscles within the framework of the existing rules. “I see no reason why, in a situation where the CMA is being denied the more far-reaching powers that it feels it needs in order to curb what it sees as the anti-competitive power of big tech firms, it would rein in its current interventionist approach where it has such broad discretion."

Carly Page is a freelance technology journalist, editor and copywriter specialising in cyber security, B2B, and consumer technology. She has more than a decade of experience in the industry and has written for a range of publications including Forbes, IT Pro, the Metro, TechRadar, TechCrunch, TES, and WIRED, as well as offering copywriting and consultancy services.

Prior to entering the weird and wonderful world of freelance journalism, Carly served as editor of tech tabloid The INQUIRER from 2012 and 2019. She is also a graduate of the University of Lincoln, where she earned a degree in journalism.

You can check out Carly's ramblings (and her dog) on Twitter, or email her at hello@carlypagewrites.co.uk.

-

Healthcare organizations are turning a blind eye to phishing attacks

Healthcare organizations are turning a blind eye to phishing attacksNews A survey reveals that most attacks go unreported, putting patient data at risk

By Emma Woollacott

-

Datatonic expands global services with Syntio acquisition

Datatonic expands global services with Syntio acquisitionNews The move marks a “key step” in Datatonic’s efforts to expand its global reach and service capabilities

By Daniel Todd

-

UK financial services firms are scrambling to comply with DORA regulations

UK financial services firms are scrambling to comply with DORA regulationsNews Lack of prioritization and tight implementation schedules mean many aren’t compliant

By Emma Woollacott

-

What the US-China chip war means for the tech industry

What the US-China chip war means for the tech industryIn-depth With China and the West at loggerheads over semiconductors, how will this conflict reshape the tech supply chain?

By James O'Malley

-

Former TSB CIO fined £81,000 for botched IT migration

Former TSB CIO fined £81,000 for botched IT migrationNews It’s the first penalty imposed on an individual involved in the infamous migration project

By Ross Kelly

-

Microsoft, AWS face CMA probe amid competition concerns

Microsoft, AWS face CMA probe amid competition concernsNews UK businesses could face higher fees and limited options due to hyperscaler dominance of the cloud market

By Ross Kelly

-

Online Safety Bill: Why is Ofcom being thrown under the bus?

Online Safety Bill: Why is Ofcom being thrown under the bus?Opinion The UK government has handed Ofcom an impossible mission, with the thinly spread regulator being set up to fail

By Barry Collins

-

Can regulation shape cryptocurrencies into useful business assets?

Can regulation shape cryptocurrencies into useful business assets?In-depth Although the likes of Bitcoin may never stabilise, legitimising the crypto market could, in turn, pave the way for more widespread blockchain adoption

By Elliot Mulley-Goodbarne

-

UK gov urged to ease "tremendous" and 'unfair' costs placed on mobile network operators

UK gov urged to ease "tremendous" and 'unfair' costs placed on mobile network operatorsNews Annual licence fees, Huawei removal costs, and social media network usage were all highlighted as detrimental to telco success

By Rory Bathgate

-

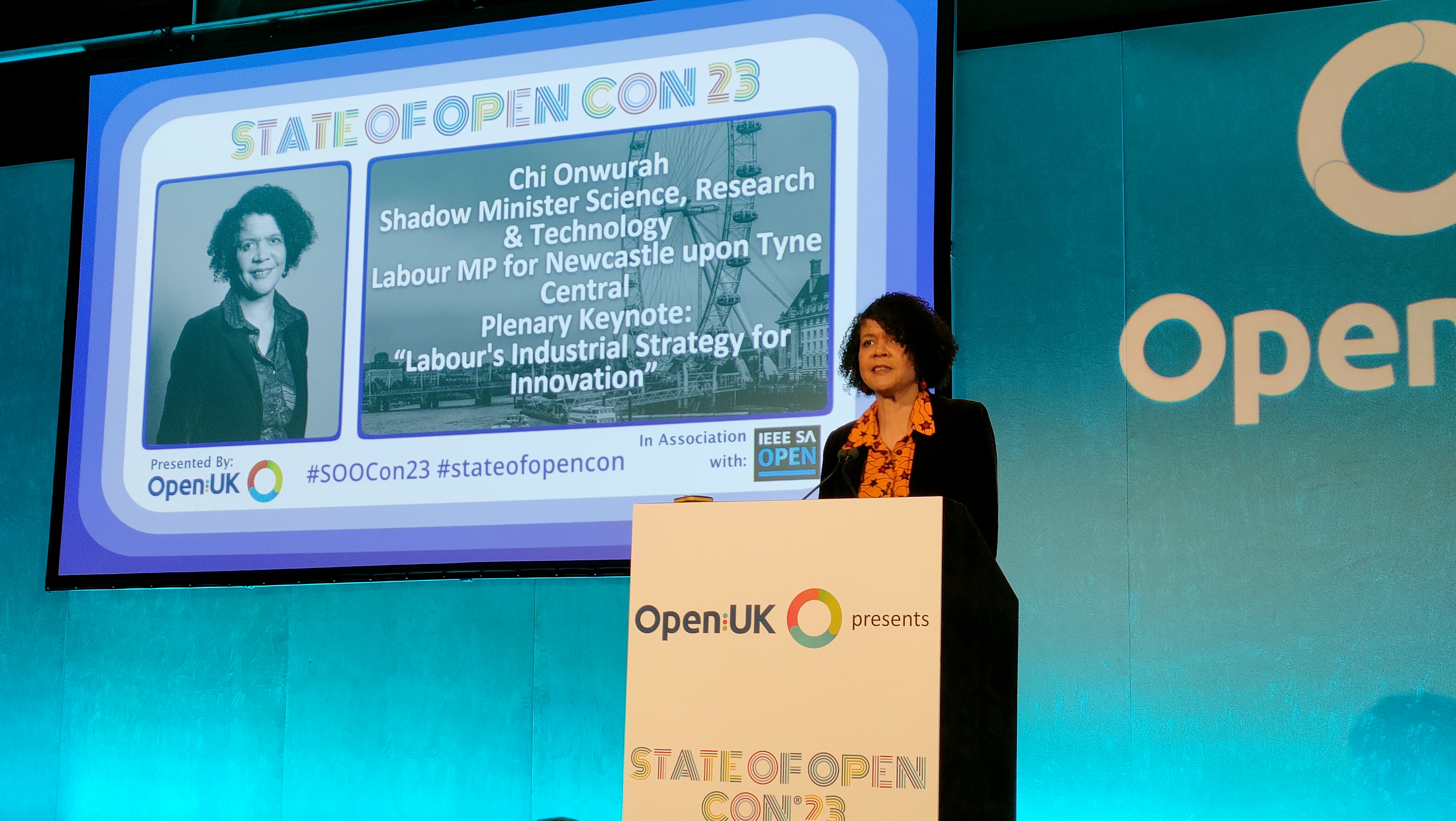

Labour plans overhaul of government's 'anti-innovation' approach to tech regulation

Labour plans overhaul of government's 'anti-innovation' approach to tech regulationNews Labour's shadow innovation minister blasts successive governments' "wholly inadequate" and "wrong-headed" approach to regulation

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet