Who needs Twitter?

Marginalised groups in particular find a lot to love about Twitter's raw nature

The current debate over Twitter's trajectory is largely focused on the service's need to get more users, in order to serve more advertisements and please its shareholders. Such is the life of a publicly traded company in today's social media market.

It remains to be seen whether Twitter will pull off this feat. Its active userbase has flatlined at around 320 million people, meaning the company is trying new things, including algorithmic filteringthat prioritises what Twitter thinks its users will want to see. For many long-time users who are accustomed to a raw feed of tweets and retweets, this could be deeply problematic.

There are many reasons for the outrage that has met Twitter's tweaks, which doesn't simply stem from a resistance to change, nor a desire to keep out the riff-raff.

That's particularly true for marginalised groups. Twitter has become very useful for giving people a voice they may have previously lacked and providing fresher angles on current events than you might find in traditional media. And much of this is down to Twitter's unfiltered, egalitarian nature.

The best-known example is so-called "Black Twitter", a primarily US scene that has seen communities gain a more prominent voice, most famously in response to incidents of police brutality. The term is understandably contentious due to its reductiveness, but it's become the subject of academic study and is now an exemplar of the way in which people can use Twitter to celebrate non-mainstream, shared identities, and to collectively put across alternative points of view.

In the case of "Black Twitter", the killings of young black men such as Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown sparked high-profile hashtags virtual rallying points such as #BlackLivesMatter and #IfTheyGunnedMeDown(a media-satirising device in which young black men would post pictures of themselves looking respectable and less respectable, and ask which one the public would see if the police shot them).

While the use of these hashtags was not exclusively limited to black people, they came from the offline frustration and outrage of black communities, and they certainly attracted a great deal of media and political attention to non-white perspectives.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

In South Africa, people's use of Twitter has also started to challenge the relatively conservative viewpoints and narratives of print and broadcast media.

Twitter had around 7.5 million users in South Africa (about 14% of the country's total population) at the end of 2015, according to World Wide Worx, a South African market research outfit. That figure was up 20% on the year before. "In emerging markets, you find that Twitter is growing steadily," said World Wide Worx chief Arthur Goldstuck. "The main reason is it gives people a voice that they never had before."

"Initially, it was a space for journalists, which made it quite intimidating, but you're increasingly finding more normal people using it in quite the same way as the journalists, politicians and celebrities did," said Gugulethu Mhlungu, a South African journalist and broadcaster. "For a long time, whoever had the most followers was the most legitimate or authoritative and respected. That's changed as well you could have a million followers but someone who has 2,000 followers, their opinion could be seen as more legitimate and authoritative."

According to Mhlungu, social media has changed the dynamics of how many South Africans find information. "Facebook did it for a bit, but Twitter has the huge advantage of being instantaneous," she said. "You can follow a thing right now, live, as it happens, and it needn't be from a reputable media outlet. As a result that's made the media a lot more responsive."

#FeesMustFall directed the national conversation in South Africa for a good portion of last year. The hashtag referred to a campaign to stop increases in university fees, which were seen as disproportionately affecting poorer black students. It provided first-hand coverage of protests that spilled over from campuses to the streets to Parliament, eliciting a violent police response but eventually a victory the government froze fee increases for the next academic year.

However, #FeesMustFall sprang from a pre-existing "Rhodes Must Fall" campaign, organised in the student residences of the University of Cape Town and others, to remove symbols of colonial oppression and make higher education more accessible to the black majority. As with the #BlackLivesMatter movement, this was something that came from offline communities.

"By the time it went onto Twitter, it was a real thing it wasn't organising itself on Twitter," said Mhlungu. "What it was doing was organising further support from other parts of the country to support what already existed outside of Twitter."

A more recent #ZumaMustFall campaign, targeting South African president Jacob Zuma over corruption, coalesced on social media. It was more heavily (although by no means exclusively) supported by whites and some accused it of racism. Twitter's South African userbase is disproportionately middle class and educated in isolation, it does not necessarily convey the grassroots voice of everyday South Africans.

In short, #ZumaMustFall suffered from being an online-first phenomenon. As Mhlungu put it: "You can't expect people to support you when you haven't spoken to them."

Of course, Twitter hashtags aren't all about mobilising people. Sometimes they're just about venting and making people reconsider their assumptions.

For many disabled people, Twitter provides a welcome opportunity to interact without having to engage with people face-to-face or leave the house things that can be serious problems not only for those with physical disabilities, but also those with anxiety or depression.

"Many marginalised groups have found Twitter to be a very useful and sometimes healing platform to share experiences, to commiserate, to realise 'wow, I've had that experience too', but also as a means of protest and consciousness-raising for people outside that community," said Lydia Brown, a disability rights advocate and writer in the US.

-

Women show more team spirit when it comes to cybersecurity, yet they're still missing out on opportunities

Women show more team spirit when it comes to cybersecurity, yet they're still missing out on opportunitiesNews While they're more likely to believe that responsibility should be shared, women are less likely to get the necessary training

By Emma Woollacott

-

OpenAI's new GPT-4.1 models miss the mark on coding tasks

OpenAI's new GPT-4.1 models miss the mark on coding tasksNews OpenAI says its GPT-4.1 model family offers sizable improvements for coding, but tests show competitors still outperform it in key areas.

By Ross Kelly

-

Who owns the data used to train AI?

Who owns the data used to train AI?Analysis Elon Musk says he owns it – but Twitter’s terms and conditions suggest otherwise

By James O'Malley

-

Big Tech AI alliance has ‘almost zero’ chance of achieving goals, expert says

Big Tech AI alliance has ‘almost zero’ chance of achieving goals, expert saysNews Companies like Microsoft, Google, and OpenAI all have competing objectives and approaches to openness, making true private-sector collaboration a serious challenge

By Rory Bathgate

-

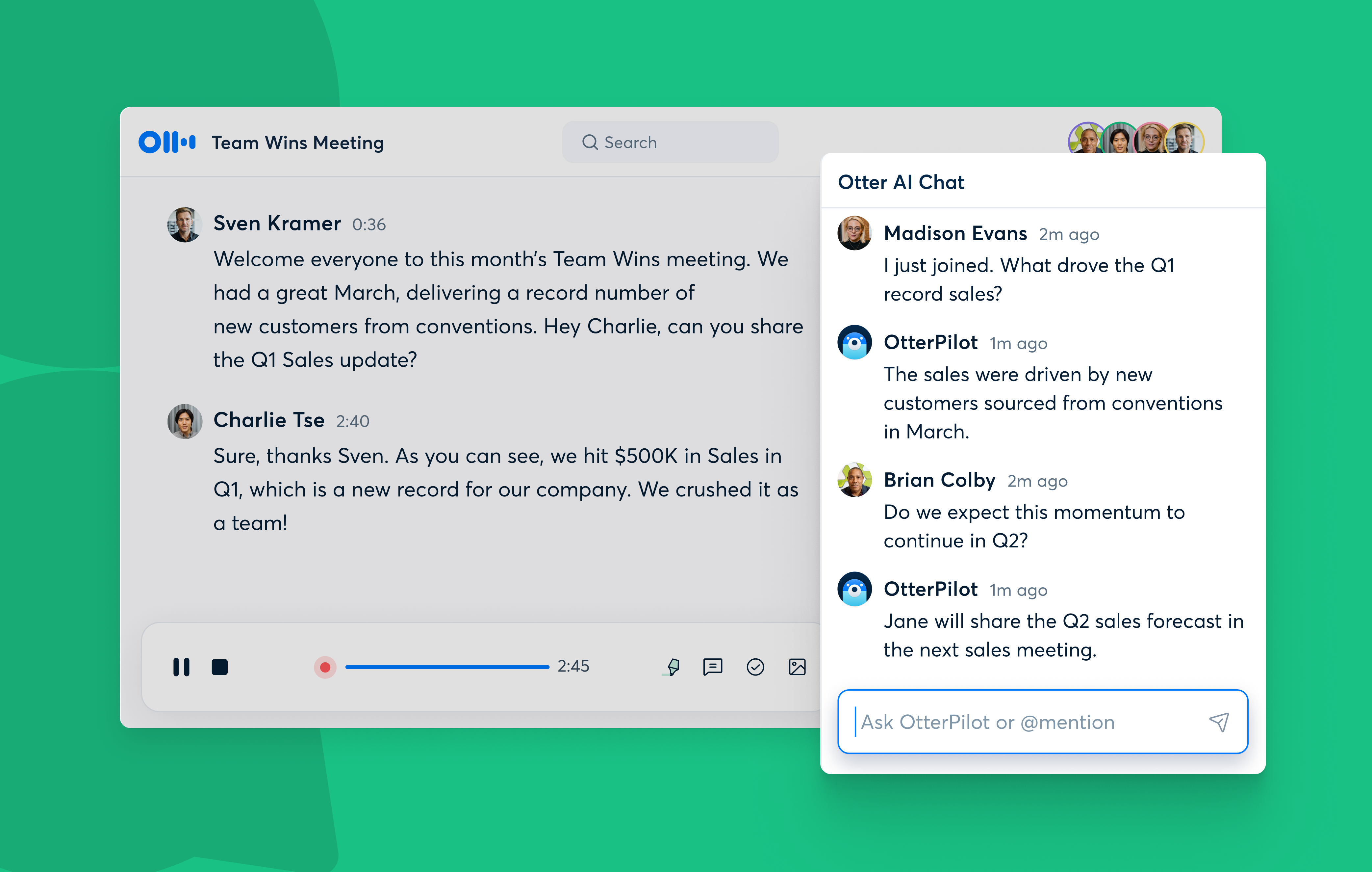

Otter.ai brings collaborative AI to meetings with Otter AI Chat

Otter.ai brings collaborative AI to meetings with Otter AI ChatNews The speech-to-text giant has set its sights on contextual AI

By Rory Bathgate

-

Slack says automation can save every employee a month of work per year

Slack says automation can save every employee a month of work per yearNews Research from Slack found that workers believe generative AI tools will revolutionize productivity

By Ross Kelly

-

Generative AI has left the metaverse in the dust

Generative AI has left the metaverse in the dustOpinion Generative AI demonstrating tonnes of business use cases only serves to highlight the hopelessness of the metaverse

By Rory Bathgate

-

Elon Musk confirms Twitter CEO resignation, allegations of investor influence raised

Elon Musk confirms Twitter CEO resignation, allegations of investor influence raisedNews Questions have surfaced over whether Musk hid the true reason why he was being ousted as Twitter CEO behind a poll in which the majority of users voted for his resignation

By Ross Kelly

-

Businesses to receive unique Twitter verification badge in platform overhaul

Businesses to receive unique Twitter verification badge in platform overhaulNews There will be new verification systems for businesses, governments, and individuals - each receiving differently coloured checkmarks

By Connor Jones

-

Ex-Twitter tech lead says platform's infrastructure can sustain engineering layoffs

Ex-Twitter tech lead says platform's infrastructure can sustain engineering layoffsNews Barring major changes the platform contains the automated systems to keep it afloat, but cuts could weaken failsafes further

By Rory Bathgate