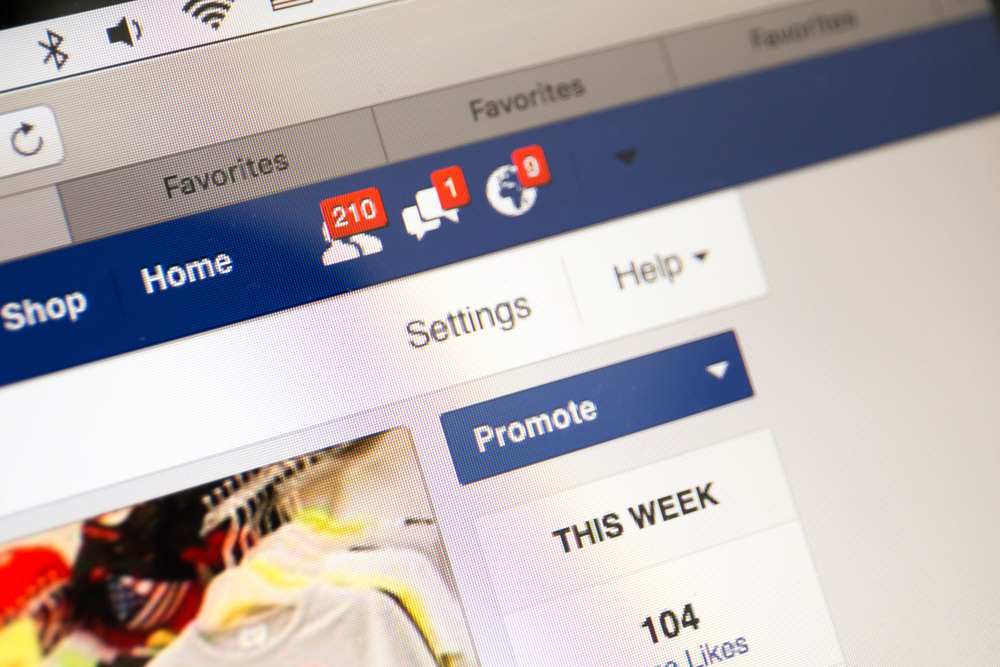

Cambridge Analytica and Facebook: What happened and has it impacted any votes?

Whistleblower Christopher Wylie has some alarming accusations about how a political influencing company acquired its data

What does Facebook say about this?

Firstly, Facebook claims that Cambridge Analytica "certified" three years ago that it had deleted information stored on the request of Facebook. The report in the New York Times suggests that at least some of it remains, which is why the company has been banned from the service.

"We are moving aggressively to determine the accuracy of these claims," the company wrote. "If true, this is another unacceptable violation of trust and the commitments they made. We are suspending SCL/Cambridge Analytica, Wylie and Kogan from Facebook, pending further information.

"We are committed to vigorously enforcing our policies to protect people's information. We will take whatever steps are required to see that this happens. We will take legal action if necessary to hold them responsible and accountable for any unlawful behaviour."

What about Cambridge Analytica?

Cambridge Analytica, for its part, denies any wrongdoing. Firstly it points to GSR being the company that broke Facebook's terms and condition and claims it deleted the data as soon as it learned it wasn't allowed access. Secondly, it denies using Facebook data in the Trump election campaign. Thirdly, it's quite insistent that the whistleblower Christopher Wylie was a contractor and not the founder of the business as some reports suggested.

This Twitter thread from the company expands on this point:

And Christopher Wylie himself?

Despite SCL CEO Alexander Nix telling MPs last month that Global Science Research company had not paid for any data for Cambridge Analytica, Wylie claims he has a contract and receipts of around $1 million showing the opposite.

His decision to go public, according to a friend, comes down to wanting to undo the damage he believes his work has done. "He created it. It's his data Frankenmonster. And now he's trying to put it right," said friend told The Guardian.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

In the same article, Wylie explains why this is important to him: "I think it's worse than bullying, because people don't necessarily know it's being done to them. At least bullying respects the agency of people because they know. So it's worse, because if you do not respect the agency of people, anything that you're doing after that point is not conducive to a democracy. And fundamentally, information warfare is not conducive to democracy."

Did this help elect Trump and get the UK to vote for Brexit?

Cambridge Analytica denies it used Facebook data in the Trump presidential campaign, though it reportedly had some involvement. It's also worth noting that the president's former chief of staff and one of many campaign managers, Steve Bannon, was a stakeholder in the company, and previously a vice president on the company board.

Reports claimed that Cambridge Analytica was also used by the Leave campaign in the EU referendum, but testimony from Arron Banks claims the company only tendered a proposal and ultimately wasn't hired.

Conflicting reports, then, but looking at the question more generally, can social profiling help sway elections? The disappointing answer to that question is twofold: 1) It depends who you ask, and 2) Nobody really knows.

To the first point, the answer varies even within Facebook. The company, until recently, had a whole page devoted to how an ad campaign helped the SNP win big at the 2015 general election. As former Facebook advertising executive Antonio Garcia Martinez said in 2016, "It's crazy that Zuckerberg says there's no way Facebook can influence the election when there's a whole sales force in Washington DC that does nothing but convince advertisers that they can."

But then it's in the interests of Facebook's ad department to say that, isn't it? But real-world evidence is pretty hard to come by. Yes, Facebook's own peer-reviewed research has proven that a simple "I voted" badge can boost voter turnout by pushing friends to do the same, which could theoretically be used by the company to tactically boost turnout in some regions, while suppressing it in others, but these options are (understandably) not open to advertisers. More importantly, you can't run two identical elections with a third control election to test the theory.

That said, this stuff is important, and goes beyond the basic numbers, which is why we wrote that 73p of Russian ad spending on the EU referendum is hardly a smoking gun for either side of the debate.

Governments likely won't like this. What's going to happen to Facebook?

The Washington Post suggests that Facebook is likely going to be investigated by the FTC to see whether it adequately protected its data or not. The likely outcome of that is "massive fines."

But more generally, this is likely a bit of a wakeup call to legislators about the power of internet giants and the importance of robust data protection laws and it's entirely possible that more regulation is on the way. Just today The Telegraph led with the news that digital minister Matt Hancock has declared that greater regulation of Facebook is required.

Downing Street has also gotten involved: "The allegations are clearly very concerning, it's essential people can have confidence that their personal data can be protected and used in an appropriate way," Theresa May's spokesman said. "So it is absolutely right the information commissioner is investigating this matter and we expect Facebook, Cambridge Analytica and all the organisations involved to cooperate fully."

Is that just hot air? Very possibly. Trying to regulate internet giants after years of letting them do their thing was never going to be easy (just look at the hard time TfL had with its Uber ban), and to be completely blunt, the UK government's position has rarely looked weaker.

But with the scandal likely to have irked multiple governments around the world, the opportunity for collaborative action makes a shift in the balance of power more likely than its been for years.

After a false career start producing flash games, Alan Martin has been writing about phones, wearables and internet culture for over a decade with bylines all over the web and print.

Previously Deputy Editor of Alphr, he turned freelance in 2018 and his words can now be found all over the web, on the likes of Tom's Guide, The i, TechRadar, NME, Gizmodo, Coach, T3, The New Statesman and ShortList, as well as in the odd magazine and newspaper.

He's rarely seen not wearing at least one smartwatch, can talk your ear off about political biographies, and is a long-suffering fan of Derby County FC (which, on balance, he'd rather not talk about). He lives in London, right at the bottom of the Northern Line, long after you think it ends.

You can find Alan tweeting at @alan_p_martin, or email him at mralanpmartin@gmail.com.