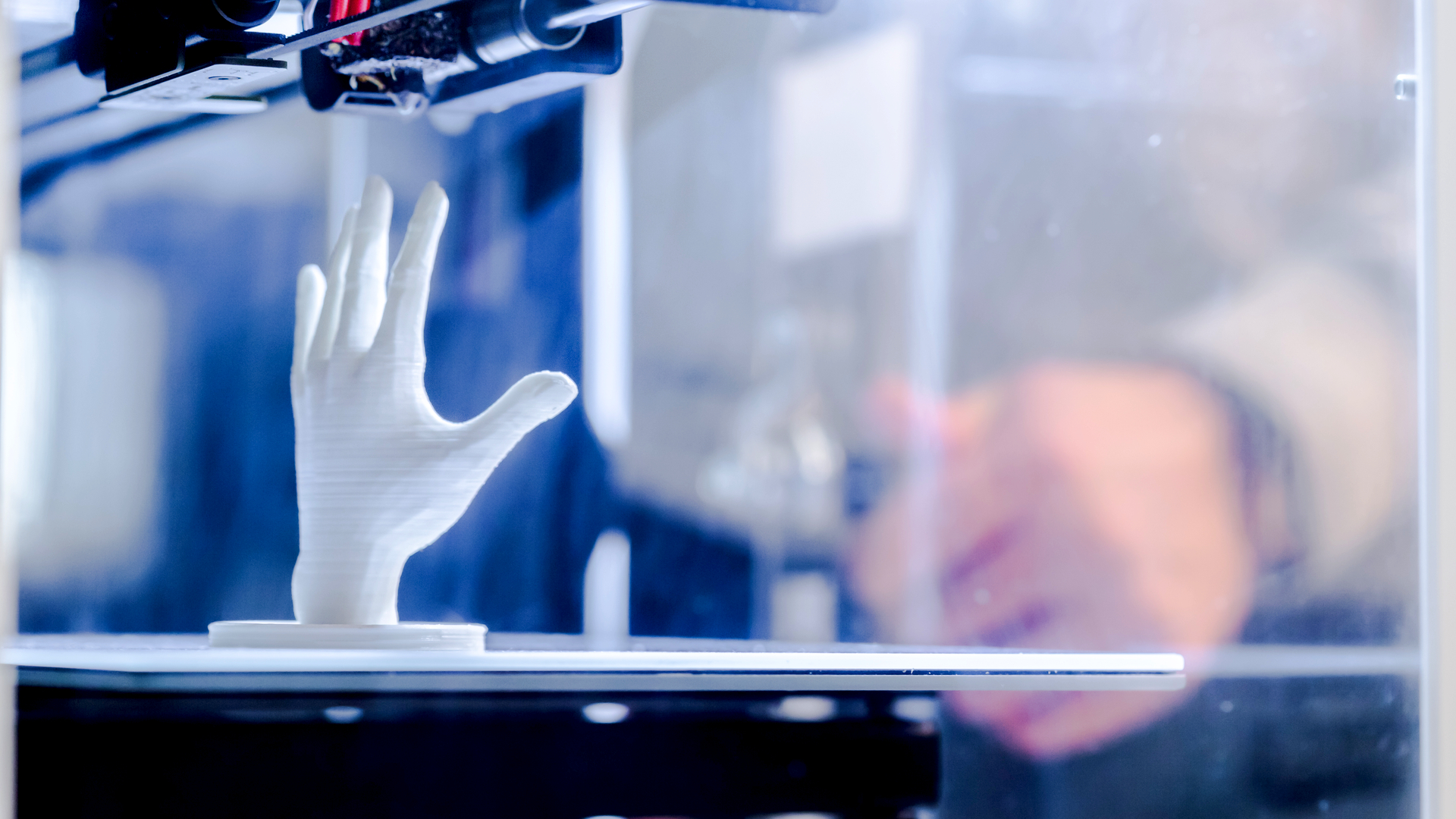

3D printing technique could create artificial blood vessels

Man-made tissue with flexible arteries could help doctor's to fight a range of vascular diseases

A "profound development" in biological fabrication could open the doors to printed arteries.

Engineers at the University of Colorado Boulder have developed a way to mimic the complex geometry of blood vessels using 3D printing.

The technique could help doctors come up up with new ways to fight vascular disease such as hypertension, by creating artificial tissue with soft, pliable arteries and veins. It uses oxygen to set 3D-printed models with different degrees of hardness.

"Oxygen is usually a bad thing in that it causes incomplete curing," said Yonghui Ding, one of the authors of the study. "Here, we utilise a layer that allows a fixed rate of oxygen permeation."

By tightly controlling how oxygen is spread during the printing process, the researchers were able to build objects with the same geometry, but with different levels of rigidity. The results were published in the journal Nature.

As part of their experiment, the engineers created a small Chinese warrior figure, printed so that the outer layers remained hard while the interior remained soft. Tough on the outside, but with a tender heart.

They also printed three versions of a simple structure: a beam supported by two rods. Depending on how hard or soft the different parts were designed to be, the structure would either stand firm or slump.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Instead of building rubbish bridges or metaphors about warriors, the technique is being eyed as a way to create artificial tissue particularly complex vessels or organs which may need to be harder in some places and softer in others.

"This is a profound development and an encouraging first step toward our goal of creating structures that function like a healthy cell should function," said Ding.

The printer can currently work with biomaterials down to a size of 10 microns; about one-tenth the width of a human hair. Future iterations, however, will aim to get this down even further.

"The challenge is to create an even finer scale for the chemical reactions," said Xiaobo Yin, senior author of the study. "But we see tremendous opportunity ahead for this technology and the potential for artificial tissue fabrication."

-

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?AI PCs are fast becoming a business staple and a surefire way to future-proof your business

By Bobby Hellard Published

-

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiatives

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiativesNews Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI have announced the launch of two new channel growth initiatives focused on the managed security service provider (MSSP) space and AWS Marketplace.

By Daniel Todd Published