In praise of the early adopters

The IT industry needs early adopters like you – and tech that fell by the wayside should still be celebrated

We’ve all encountered laggards. “One of those fancy new smartphones, is it?” they smirked a decade ago, nodding towards the black slab you just pulled out of your pocket. “My old Nokia 3210 does everything I need. Fancy a game of Snake?”

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this attitude. They swore by their device’s long battery life and robust nature, just as you swore when your phone fell to the floor with a sickening thud. But few companies target the laggard market.

I thought of the laggards when I heard, in mid-July, that Valve had announced a new portable handheld console designed to play PC games. Built on Linux and resembling a Nintendo Switch in many respects, the Steam Deck aims to prise PC gamers away from their computers and into the fresh air – and it sold out in minutes.

The people buying it are on the other side of the spectrum to the laggards. They’re the innovators and early adopters – folk, I suspect, who are just like you – and, as drivers of the tech industry, they are very important indeed.

Taking a risk

Imagine, if you will, that hundreds of thousands of people hadn’t laid out 99 notes on Windows 1.0 in 1985; that instead they’d listened to the critics who, two years after first catching wind of the operating system, had written it off as “vapourware”.

Or, imagine that 200 people hadn’t snapped up an Apple I assembled circuit board at a cost of $666.66 shortly after it went on sale in July 1976. Where would Jobs and Wozniak have gone next? Would they have gone on to develop the Apple II the following year, or would computer enthusiasts have been forced to look elsewhere?

In fact, the early adopters kept Apple ticking along until VisiCalc launched in mid-1979, and helped the computer leap into the professional market – to the next group along, the so-called “early majority”. Similarly, early adopters embraced Motorola’s cellphones in the US in 1983 even though some considered them to be rich people’s toys.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

So we owe a debt of gratitude to these digital drivers, and the vast sums of cash they splash out. The first console to use ROM cartridges and a microprocessor, the Fairchild Channel F, cost $170 on its 1976 debut, which is the equivalent of $772 today. The first commercially successful portable computer, the Osborne 1, cost $1,795 in 1981 – that’s $5,000 adjusted for inflation.

Sometimes it pays off; often it doesn’t. More than 50,000 people bought the first Macintosh within eight weeks of its going on sale in February 1984, perhaps thanks to the lavish $1.5 million television advert directed by Ridley Scott. But by January 1986 the Macintosh Plus had appeared with double the memory and a price tag some $700 cheaper.

Later, in August 1998, Apple released the iMac G3. It had its first revision just a month later, upping the amount of video RAM from 2MB to 6MB. Further tweaks came in January and April of the following year, introducing new colours and faster processors.

It sounds like the early adopters get a raw deal – yet a good number of Apple fans still like to get in first, even today. The secret is the product has to be one that will quickly assimilate into the buyer’s lives. Otherwise, that the prestige of getting in early soon wears off.

Spreading the word

RELATED RESOURCE

Shining light on new 'cool' cloud technologies and their drawbacks

IONOS Cloud Up! Summit, Cloud Technology Session with Russell Barley

There can be a backlash from time to time. Apple caused an outcry when it reduced the price of the original iPhone by $200 two months after it went on sale; Steve Jobs responded by issuing a $100 credit to those who’d paid the higher price. Amazon upset early adopters when it released the Kindle 2 in 2009 without mentioning that the Kindle DX was on its way – and then lopping a good chunk off the former’s price once it arrived. The Nintendo 3DS also had its price slashed from £270 to £170 within five months of launch, though that was to kickstart sluggish sales.

In the main though companies work hard to keep early adopters onside, and not just for goodwill. “Early adopters of a technology are often evangelists and influencers for later adopters,” said JP Eggers, associate professor of management at New York University. “They’re more valuable than a comparable number of later adopters.”

Academic researchers James C Brancheau and James C Wetherbe have long agreed. In their 1990 paper “The Adoption of Spreadsheet Software”, they noted that early adopters were not only highly educated, but “more attuned to mass media, more involved in interpersonal communication and more likely to be opinion leaders”. Without them, the tech landscape would be very different.

Indeed, good early adopters don’t just advertise to others: they play around, tweak settings and push their new devices to the limits, providing feedback that helps new products grow into the mainstream.

“As customers, early adopters are vital, otherwise many products simply wouldn’t get to version 2.0,” said Amstrad’s former group technology consultant Roland Perry. “I’m a strong believer that the best way to create a product with a hope of a future is to employ early adopters, with experience in similar technologies, on the team.”

Perry is well aware of what happens to products that don’t benefit from early adopter investment. In 1990, Amstrad upgraded its personal computer range with new 464 and 6128 Plus computers, focusing on affordability rather than trying to compete with the new generation 16-bit Commodore Amiga and Atari ST systems. “The end user doesn’t know whether it’s 16-bit, 8-bit, or if it’s working with gas or steam or with elastic bands,” declared boss Alan Sugar at the time.

Unfortunately, the end user did know – or at least the early adopters did. There were few early sales and little excited chatter from anyone who did buy. Instead, customers moaned that there were too few games, and that the benefit of the enhanced hardware wasn’t immediately visible. “There’s was nothing ‘early adopter-ish’ about it,” reflected Perry, who also worked on the hugely successful PCW range. “If anything it was at the other end of the spectrum.”

Kickstarting new tech

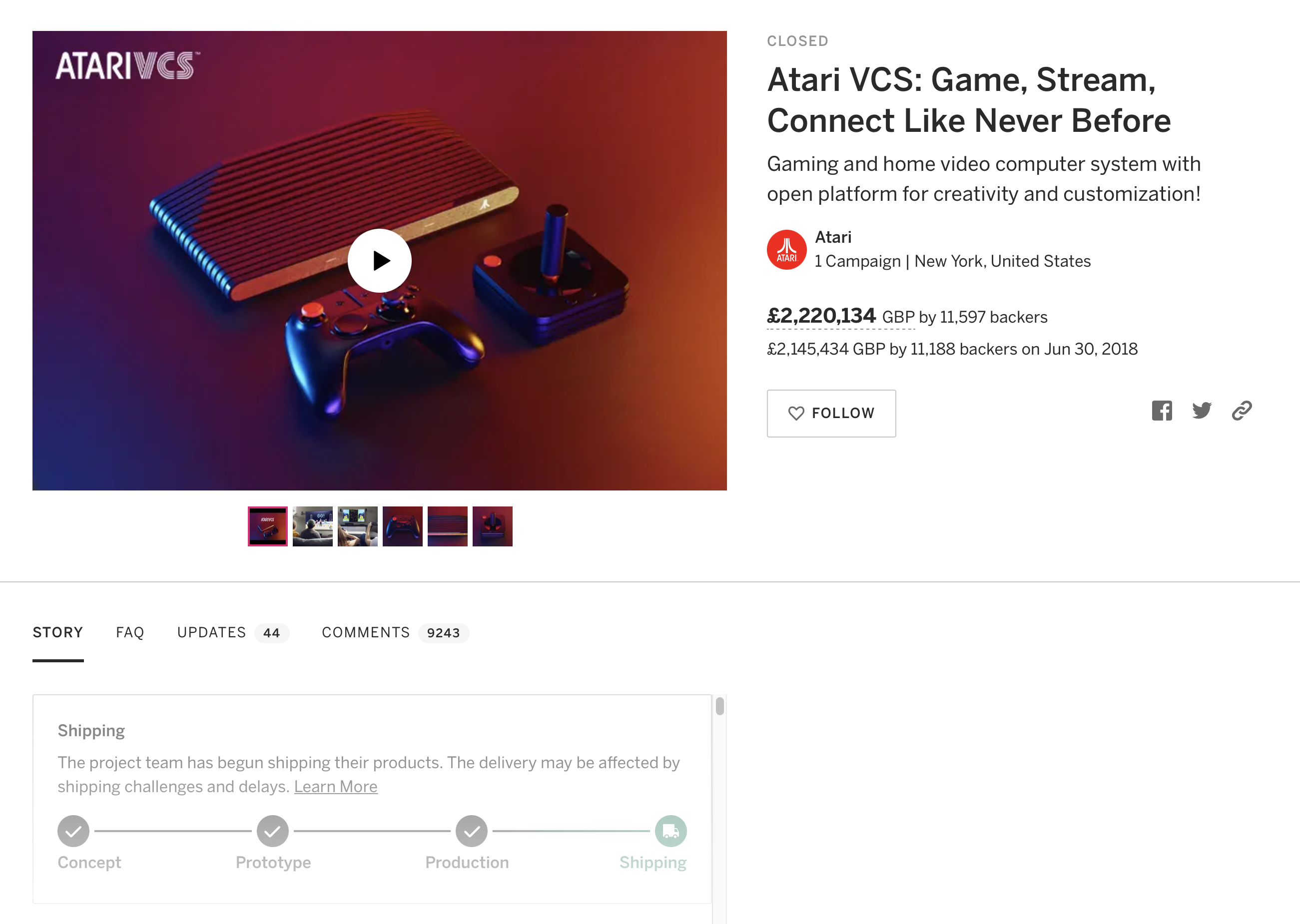

It’s fair to say that a lack of early adoption points towards a flop. But there are also cases of tech failing to catch on despite being snapped up in the initial weeks – or even before it’s been made. The game console Ouya is a prime example: it was financed by 63,416 backers to the tune of £8.6 million on Kickstarter in 2013, yet discontinued two years later.

In this case, the problem was partly due to the console being technically flawed, but also came down to a lack of emotional investment. “Kickstarter is a bit odd, because people make adoption decisions without knowing what the product is,” explained Professor Eggers. “So there often are products that sound really cool, but then when people get them they actually suck. Kickstarter is also rife with the fear of missing out, so adoption decisions aren’t always very rational.”

This makes attracting the “early majority” even harder. “Early adopters are really different from later adopters in terms of demographics and their preferences,” said Eggers. “This is why we get phenomena like the challenge of ‘crossing the chasm’, where early successful firms struggle to gain traction with the mainstream market.”

Pointing the way

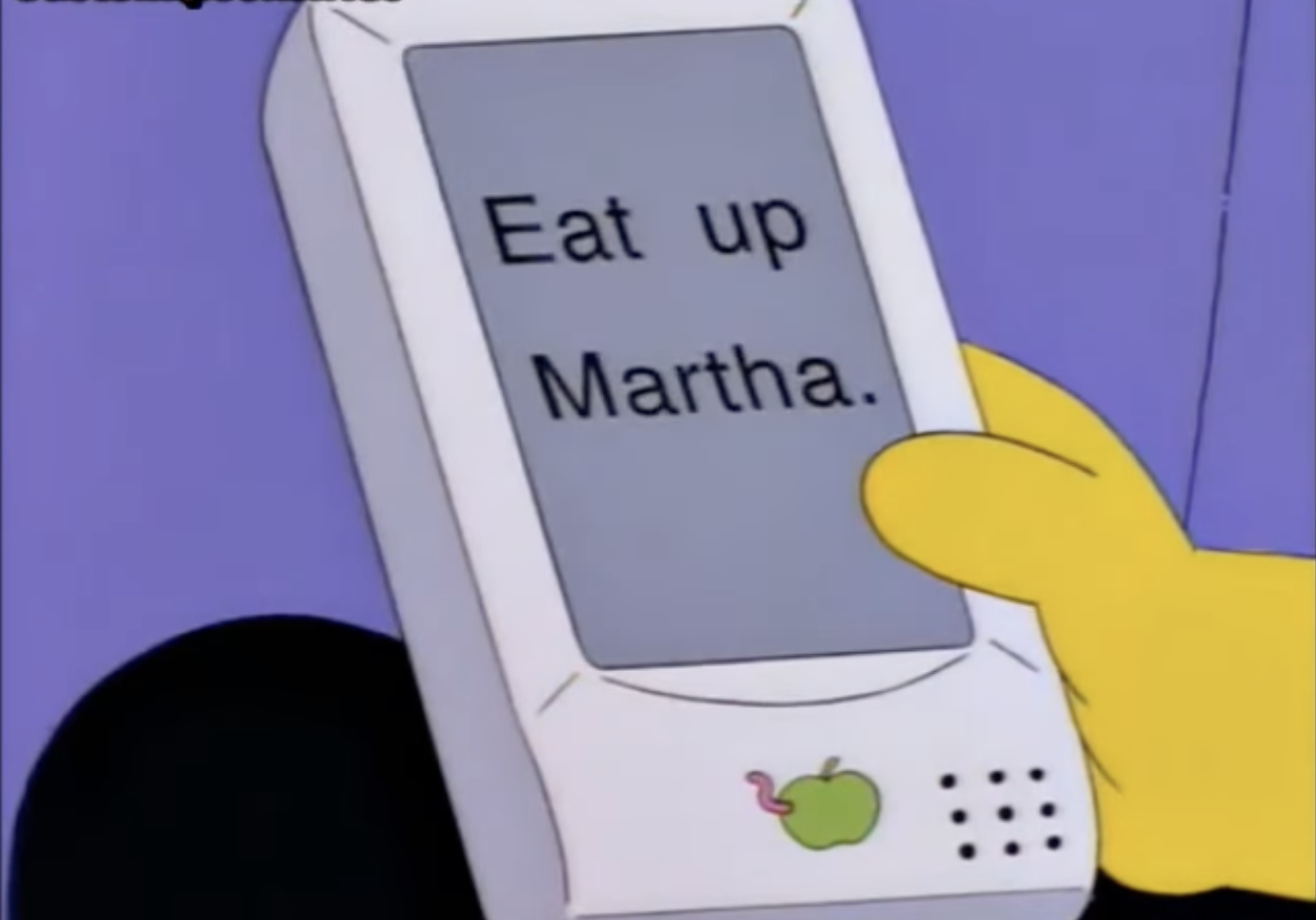

Failure doesn’t have to be a dirty word. While it’s desirable to cross over into the mainstream and make a huge impact, there are still benefits to manufacturers having a bash if things don’t work out. Just look at Apple’s Newton MessagePad – a product that was, with hindsight, years ahead of its time – as proof of that.

Launched in 1993, it sold 50,000 units to early adopters and became one of the firm’s fastest-selling products. Unfortunately, despite its promise to make computing truly portable, its signature handwriting recognition feature was woeful – making it the butt of jokes to such an extent that it was even lampooned in an episode of The Simpsons.

Apple stuck with it through various iterations before giving up on the Newton in 1998. But when the company came back 12 years later with the iPad, it was able to draw on the experience and feedback from early adopters to finally perfect the product.

There are other examples where early adopters have helped manufacturers recognise the potential of an idea. The 68,929 backers who stumped up a total of £10.2 million for the Pebble smartwatch on Kickstarter in 2012 showed the likes of Apple and Samsung that there was an appetite for wearables – particularly given how engaged developers were in creating apps and watch faces.

Similarly, when Sega launched the Dreamcast in 1998, early adopters bought more than 200,000 units in 24 hours and 500,000 within two weeks. Though the console subsequently faltered, its built-in modem ushered the dawn of online console games. Within a month of the launch of SegaNet, 1.55 million Dreamcasts were registered online. Such popularity didn’t go unnoticed.

Being an early adopter comes with hazards. Buying tech within days or weeks of its introduction can feel like a voyage of discovery, particularly if features are poorly documented or not yet entirely stable. You may find that a new device isn’t compatible with the old, forcing you into more tech upgrades, and of course you’ll almost always be buying at the highest price.

But that’s part of the excitement of being ahead of the curve. It’s what allows innovation to continue, monopolies to be broken and tech to move on. That Nokia 3210 was once exciting, and lots of retro tech continues to be. Early adopters have made a big impact in the past, and they’ll no doubt continue to do so for as long as companies keep coming up with new technologies.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Amazon’s Thin Client for business is an IT department’s dream

Amazon’s Thin Client for business is an IT department’s dreamOpinion This upgraded TV Cube is the affordable answer to hybrid work devices we’ve been searching for

By Bobby Hellard Published

-

Apple iPad Air (2020) review: The executive’s choice

Apple iPad Air (2020) review: The executive’s choiceReviews With the iPad Air’s most recent redesign, Apple has delivered the best bang-for-buck tablet money can buy

By Connor Jones Published

-

Apple is experimenting with attention sensors to save battery life

Apple is experimenting with attention sensors to save battery lifeNews Your next Apple device may shut down if you are not paying attention to it

By Justin Cupler Published

-

Panel Profile: RoosterMoney CTO Jon Smart

Panel Profile: RoosterMoney CTO Jon SmartIT Pro Panel We get face-to-face with one of the IT Pro Panellists

By IT Pro Published

-

Amazon unveils new Fire tablets, including new kid-friendly models

Amazon unveils new Fire tablets, including new kid-friendly modelsNews Meet the thinner, lighter, and brighter Fire HD 10

By Mike Brassfield Published

-

Apple unveils M1-powered iPad Pro and iMac at April 2021 event

Apple unveils M1-powered iPad Pro and iMac at April 2021 eventNews The new Apple Silicon hardware will be available to order from April 30

By Justin Cupler Published

-

iPad Air 2020 debuts with A14 Bionic chip and USB-C

iPad Air 2020 debuts with A14 Bionic chip and USB-CNews Apple touts its latest flagship tablet as the “most powerful” iPad Air ever

By Sarah Brennan Published

-

Apple reveals iPadOS at WWDC19

Apple reveals iPadOS at WWDC19News Cupertino's tablet range breaks free of iOS with new dedicated software

By Jane McCallion Published