How businesses can fight the mounting e-waste crisis

It makes business sense, not just environmental sense, for organisations to reduce their technical wastage

As we move into the festive season and temperatures take a tumble, dad jokes querying the existence of climate change will almost certainly emerge around the dinner table. It’s barely a laughing matter, however, and leaders around the world are increasingly grappling with the scale of the climate crisis – as COP26, hosted last month in Glasgow, attempted to demonstrate. Lost among the headlines of China and Russia’s involvement, coal power stations and emission targets, though, was e-waste, a key issue that’s sadly been neglected.

To illustrate the scale of the problem, British artist Joe Rush and technology reseller musicMagpie collaborated on a statue of the world leaders attending this June’s G7 summit in Cornwall. Dubbed 'Mount Recyclemore', the structure was made entirely of 20,000 pieces of discarded tech.

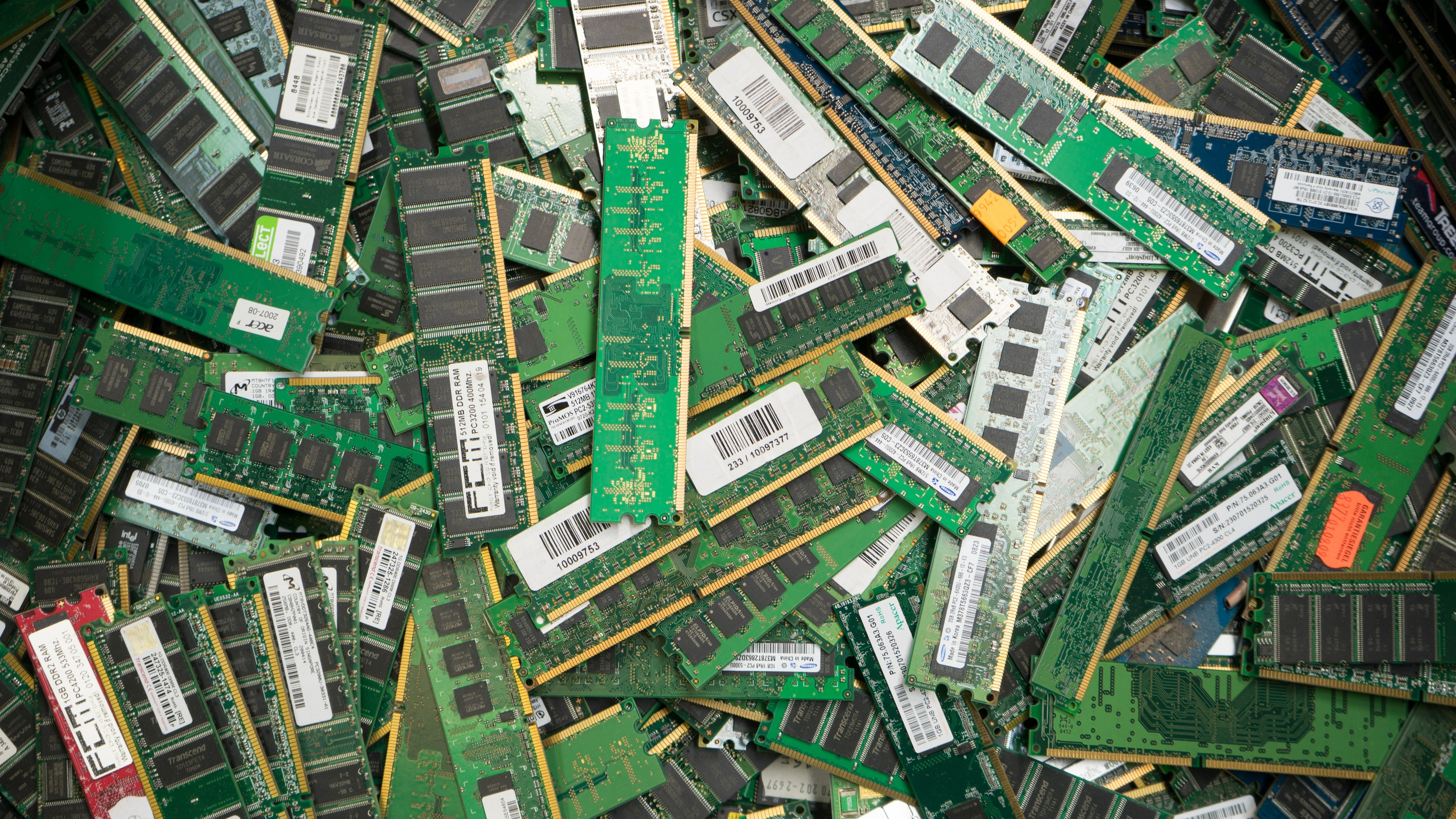

This striking homage highlighted how much technical equipment is thrown away each year. Roughly 53.6 tonnes of e-waste was generated worldwide in 2019, surging 21% in five years, according to the UN’s most recent global e-waste monitor. This volume of e-waste, which is expected to rise to 74 tonnes by 2030, is fuelled by a habit to continuously refresh technology, says Mirjam Werner, associate professor in the business society management department at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

Artist Joe Rush and musicMagpie collaborated on Mount Recyclemore ahead of the 47th G7 Summit this June

“It's not only the products, but it's also the support that goes with them,” Werner tells IT Pro. “Even if you want to use your mobile phone for more than four years, applications are being developed at such a rate that they require processing speeds the mobile phone can't deal with. “The marketing push to need a new phone, need a new tablet, need an in-between tablet that has the same features as your iPad – but your life will be greater for it – is a big issue when we talk about wastage. That’s because consumers get to a point where they have lots of screens in the home without really knowing why, and, after five years, it won't work anymore, so you can't pass it on to someone in need.

Fighting planned obsolescence

Outdated and irreparable equipment is a deliberate manoeuvre, Werner argues, which is where ‘take back’ and ‘right to repair’ laws come in, so people are liberated to reuse or repair devices to give them a longer lifespan. Indeed, the right to repair is becoming more popular, with Apple’s concession that iPhone and Mac users were now allowed to repair their devices, in particular, raising eyebrows. Specific details are yet to be published and Apple has so far only enrolled the latest iPhone 12 and iPhone 13 series models into the scheme.

Nevertheless, it’s a positive move, but independent technology analyst Scott Stonham says big tech may need to be incentivised to do more. “The idea behind the right to repair bill is to try and make sure that when my battery dies I have the right to replace it rather than replace the whole device, which is the behaviour that big tech companies are encouraging,” he says.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

“The incentivisation piece is important too, because so many companies when they do their financial reporting, a big part of what they report is going to be on units sold rather than units fixed. There needs to be a way of reporting that focuses on sustainability and will shine a light on those things to make it easier for businesses to claim credit in that area.”

The iPhone 13 (pictured) is among the first devices included in Apple's right to repair scheme

Werner adds that more help is needed for executives to put together effective plans to reduce their wastage. Financial support, such as tax breaks, or advice identifying where “quick wins” can be made from e-waste reduction, are both possible, for example. “Often, however, one of the problems is that smaller businesses have the willingness but not the capacity to actually take advantage of the help offered,” she warns. “I think that's a pity because once the smaller businesses also start to move with larger companies, there’s an industry change going on – which can influence consumers too.”

Supply chain crackdown

We, as consumers, might be the largest contributors to e-waste, but businesses are also aiming to reduce their footprints. Although carbon offsetting may be seen as one answer, meaningful reductions in waste come when businesses are able to run efficient audits.

Such a process can become a stumbling block for businesses that don’t know where to start, however, according to Stonham. Any amount of progress is positive, though, he says, as it ultimately kick-starts the journey, while establishing the parameters and metrics of success will help organisations consistently reduce their e-waste over time. Businesses must also go further, however, and question their suppliers over where products are sourced, and what they’re doing to reduce their environmental impact, he continues.

“A lot of IT support or IT providers are now being facilitated by the big tech companies to come up with plans for how to transition to a circular business model,” Stonham says. “If your business is using a third party for support, the first thing to do is ask them what they're doing about e-waste, and how to get more information. The more that happens, the quicker the big tech companies trickle down that information and provide the tools that are needed to SMBs.”

Going around in circles

Reducing technical wastage, in absolute terms, isn’t the only way businesses can fight the mounting crisis. Both Werner and Stonham suggest converting to a circular business model, in which materials and products are sourced and disposed of responsibly, is the best way for businesses to address e-waste. The EU, incidentally, is devising policies to enact a circular economy across Europe, with an action plan detailing ambitions to regulate how electronic products are designed and manufactured.

Werner adds that by implementing a circular economy and using more recycled materials, technology companies wouldn’t be as heavily affected by global events like the semiconductor chip crisis. “Of course, we can’t say that for sure, and part of the chip problem was the distribution and supply chain issues,” she cautions. “I do believe, however, that, had companies had a better circular approach to the recovery of used minerals and materials core to chip-making, as well as the ability to reuse them, then those companies wouldn’t have been hit as hard as those still dependent on virgin material.”

The volume of discarded technical equipment is only expected to rise each year, contrary to the ambitions world leaders set out at COP26. Until concrete progress is made on implementing measures to fight the crisis, it’s unlikely the e-waste debate will progress beyond organisations, consumers and policymakers going around in circles.

Elliot Mulley-Goodbarne is a freelance journalist and content writer with six years of experience writing for B2B technology publications, notably Mobile News and Comms Business. He specialises in mobile, business strategy, and cloud technologies, with interests in environmental impacts, innovation, and competition. You can follow Elliot on Twitter and Instagram.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published