After decades of data center trauma, tech giants have finally killed the leap second

From 2035, time will begin to fall out of sync with reality but, on the plus side, it’ll be much easier to run data centers

Keumars Afifi-Sabet

We all know the Earth takes 24 hours to complete one rotation. The only problem is that it doesn’t. A host of irregularities, caused by everything from the laws of angular momentum, to the tides, to even natural events such as earthquakes means, in any given year, our clocks could find themselves slipping ever so slightly out of sync with the observed reality.

READ MORE

That’s why, since 1972, scientists have occasionally voted to add a “leap second” to the calendar, either on 30 June or 31 December, to keep clocks reflective of our actual position in space. But all of this could be about to change. To date, they’ve added 27 seconds.

Following a vote at the 27th General Conference on Weights and Measures last November, however, scientists will no longer balance time by adding a leap second by 2035. This follows lobbying from the likes of Meta and Google.

But why are tech giants so desperate to rid the world of the leap second?

Why tech giants hate the leap second

“We’re supporting an industry effort to stop future introductions of leap seconds and stay at a current level of 27,” Meta’s production engineer Oleg Obleukhov and research scientist Ahmad Byagowi said in a blog post last year. “Introducing new leap seconds is a risky practice that does more harm than good, and we believe it is time to introduce new technologies to replace it.

“Because it’s such a rare event, it devastates the community eerie time it happens. With a growing demand for clock precision across all industries, the leap second is now causing more damage than good, resulting in disturbances and outages.”

RELATED RESOURCE

Get an understanding of the real business value of AI-powered automation and the opportunities available.

“After 50 years of doing this, we realise we suck at change management,” says Patrick McFadin, VP of developer relations at DataStax, a platform for real-time application development.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

The problem is that, in the modern world, every second really does count, as data centers rely on split-second accuracy to keep systems up and running. “If you look at all the outages that have happened in every cloud, most times it's because of a human,” says McFadin. “Rarely are they because of something big, like a hurricane or a tornado. We plan for those.

“The data center loses power, we can handle that. But if somebody changes one line on a configuration file and hits enter…”

What will happen after 2035?

What makes leap seconds particularly tricky for systems to deal with is that unlike a 29 February rolling around once every four years, they’re fundamentally unpredictable – and only happen in response to natural events.

Time cannot go backwards, that's not okay

Patrick McFadin

Reddit, for example, sustained an outage in 2012 due to a leap second, with the site inaccessible for 30 to 40 mins. The time change caused the high-resolution timer to be confused, which caused the servers to behave erratically, locking the CPUs. Cloudflare also sustained outages due to the leap second in 2017, with a bug knocking some servers offline.

“Our infrastructure isn't built with the idea that it can deal with leap seconds,” says McFadin. He describes how one difficulty is that leap seconds mean violating some of the core checks normally put in place to, for example, ensure database transactions are authentic.

This runs head first into a potentially dangerous hypothetical: there’s no reason why, under the current system, scientists couldn’t determine that in response to some natural phenomena that a second needs to be not added – but removed.

“Time cannot go backwards, that's not okay,” says McFadin.

READ MORE

“If we manually reduce time by a second, all those checks come into play, and a system will be like, ‘oh, something broke’, and it'll lock up.”

There’s one lingering question, however. What happens after 2035 when the changes come into force? Won’t that cause a big difference between observed time and our own time keeping? The good news is scientists estimate that, by the end of the century, we’ll only have drifted by a minute – and even better, it will be someone else’s problem.

- Keumars Afifi-SabetContributor

-

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?AI PCs are fast becoming a business staple and a surefire way to future-proof your business

By Bobby Hellard

-

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiatives

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiativesNews Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI have announced the launch of two new channel growth initiatives focused on the managed security service provider (MSSP) space and AWS Marketplace.

By Daniel Todd

-

Google shakes off tariff concerns to push on with $75 billion AI spending plans – but analysts warn rising infrastructure costs will send cloud prices sky high

Google shakes off tariff concerns to push on with $75 billion AI spending plans – but analysts warn rising infrastructure costs will send cloud prices sky highNews Google CEO Sundar Pichai has confirmed the company will still spend $75 billion on building out data centers despite economic concerns in the wake of US tariffs.

By Nicole Kobie

-

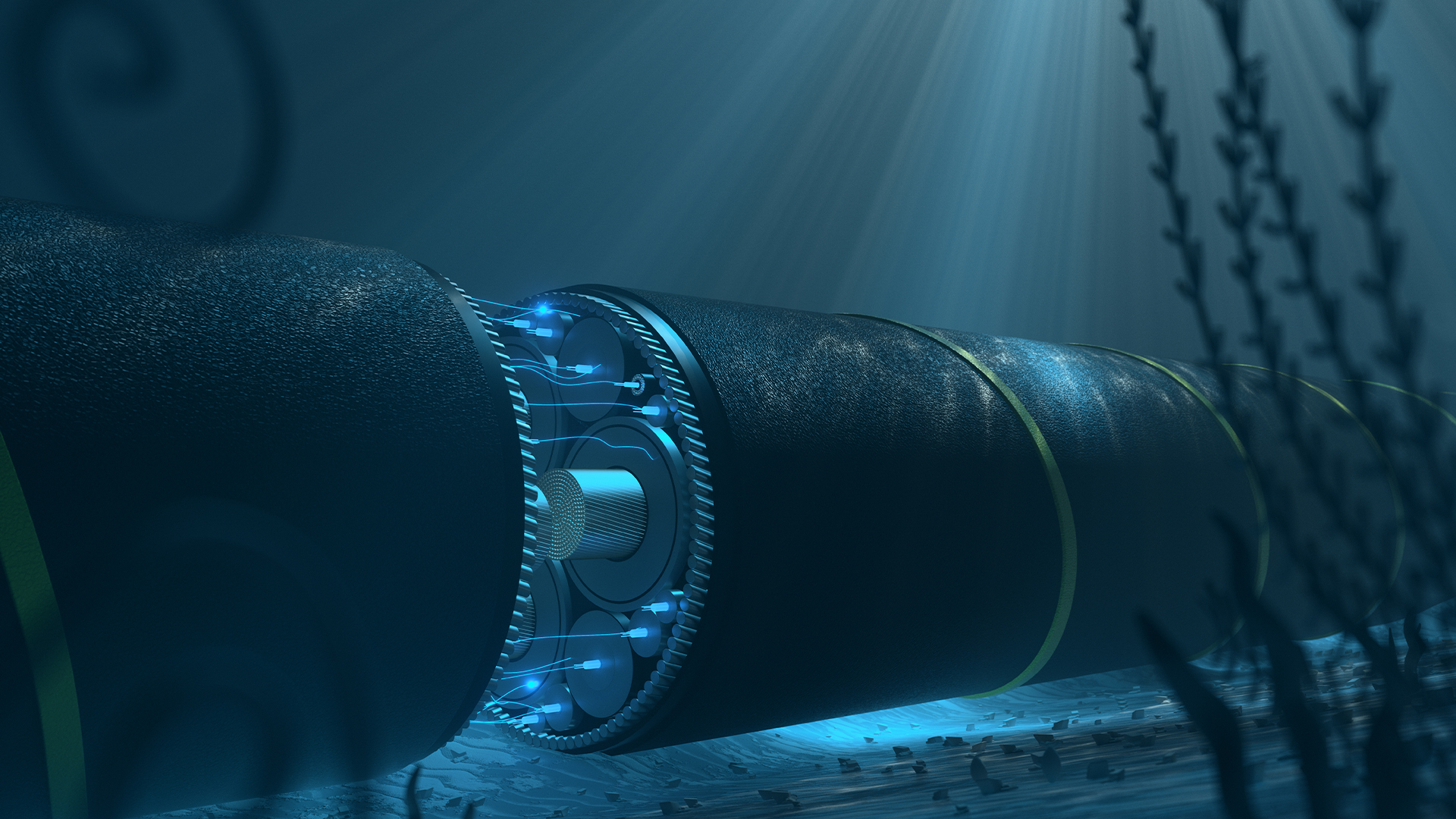

Meta is building the world’s longest subsea cable: Project Waterworth will span 50,000 km and connect five continents – and it aims to boost global connectivity and AI services

Meta is building the world’s longest subsea cable: Project Waterworth will span 50,000 km and connect five continents – and it aims to boost global connectivity and AI servicesNews Meta has announced plans to build the world's longest subsea cable in a bid to supercharge global connectivity and drive AI innovation.

By Emma Woollacott

-

Ireland has become a “data dumping ground” for big tech

Ireland has become a “data dumping ground” for big techThe sharp increase in data center projects may be threatening Ireland's net-zero aspirations

By Nicole Kobie

-

Meta wants to join the big tech nuclear club

Meta wants to join the big tech nuclear clubNews Meta has become the latest big tech company to explore the use of nuclear energy to power data centers.

By Nicole Kobie

-

Meta just unveiled plans to spend $10 billion on its largest-ever data center

Meta just unveiled plans to spend $10 billion on its largest-ever data centerNews The Louisiana facility will be optimized for AI workloads

By Emma Woollacott

-

Data centers will be critical to UK economic growth in the coming decade – but researchers have warned of a ‘data doomsday’ unless energy infrastructure is improved

Data centers will be critical to UK economic growth in the coming decade – but researchers have warned of a ‘data doomsday’ unless energy infrastructure is improvedNews With TechUK calling for improved grid connections and easier access to renewable energy, a new study warns that the world's entire electricity supply may not be enough

By Emma Woollacott

-

Europe needs more energy and better grids to meet data center power demands in the age of AI

Europe needs more energy and better grids to meet data center power demands in the age of AINews Data center energy demands in Europe are set to triple by the end of the decade, and that means countries will need to boost investment in sustainable power sources and upgrade grid infrastructure.

By Nicole Kobie

-

Data center water consumption is spiraling out of control

Data center water consumption is spiraling out of controlNews Energy usage might be front of mind amid the AI era, but surging data center water consumption is raising serious concerns among industry stakeholders

By Solomon Klappholz