Inside Lumi, one of the world’s greenest supercomputers

Located less than 200 miles from the Arctic Circle, Europe’s fastest supercomputer gives a glimpse of how we can balance high-intensity workloads and AI with sustainability

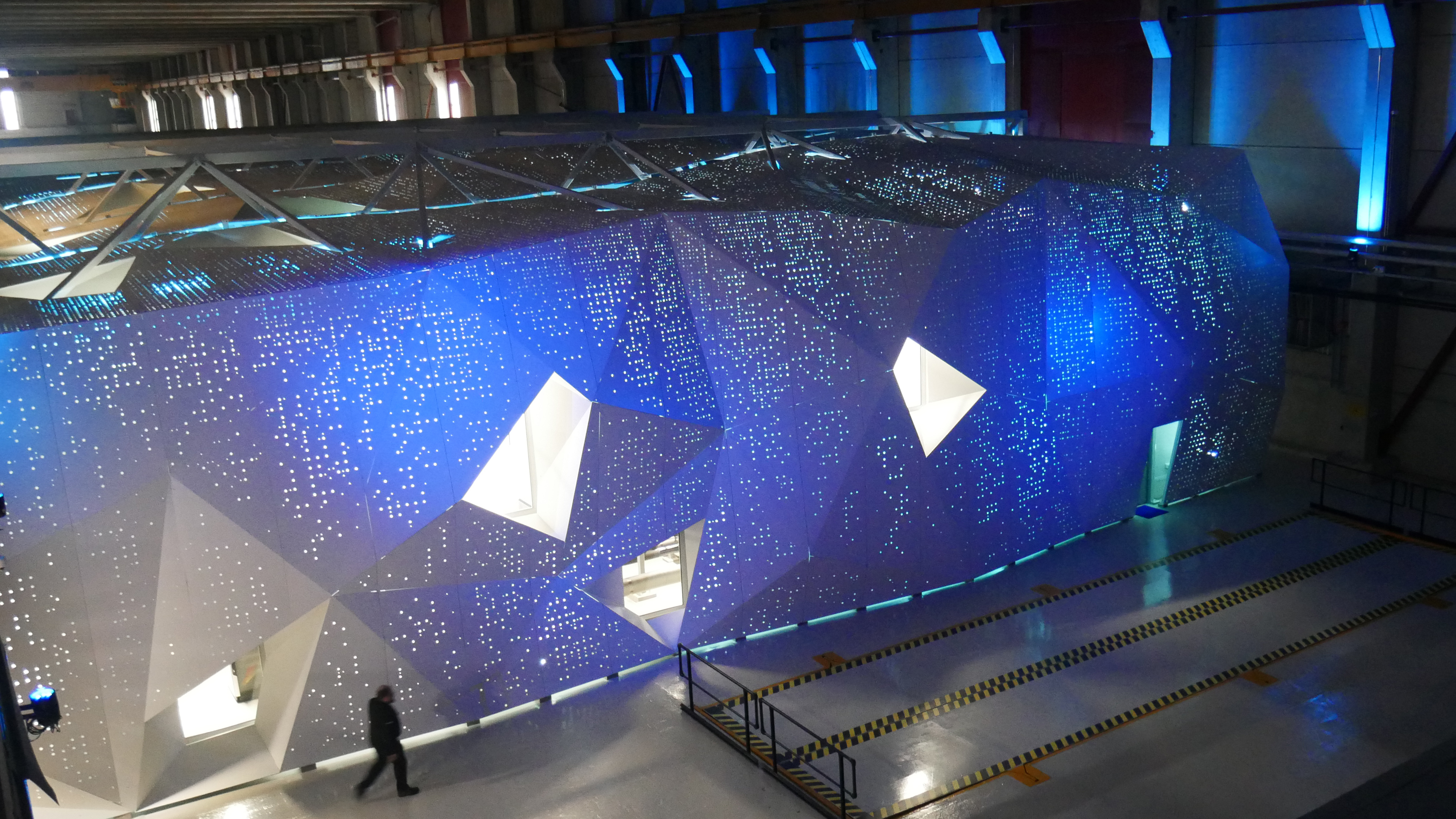

What do you think of when you imagine a supercomputer? Rows and rows of servers, certainly, but what about the facility it’s housed in? Whatever springs to mind, it’s probably not a papermill, yet that’s exactly where I went when I traveled to see Lumi, the fastest supercomputer in Europe.

Affectionately referred to as ‘the Queen of the North’, Lumi – which both stands for Large Unified Modern Infrastructure and is the Finnish word for snow – is tucked away on the outskirts of the city of Kajaani. The area, once known for its forestry and paper manufacturing, is now making a name for itself in IT, according to Pekka Manninen, director of science and technology at CSC, which runs both Lumi and the neighboring Finnish national supercomputers, Mahti and Puhti.

While Lumi is located in Finland and run by a company that’s 70% owned by the Finnish state and 30% by Finnish higher education institutions, it’s very much a European project. It’s part of EuroHPC, which also comprises Leonardo in Italy and Marenostrum 5 in Spain.

EuroHPC, which is a public-private partnership, also provides some of the funding for Lumi, along with the 11 European nations that make up the Lumi Consortium.

How big is big?

Physically, Lumi’s housing is imposing. It occupies most of a former machine hall, which is about two stories high, and roughly 50 meters long. In accordance with its namesake, Lumi was designed to evoke the idea of a snow bank: White, with small cut-outs that let light sparkle through from the data center inside and is lit from the outside in blue.

Inside, according to Top500, is the fifth most powerful supercomputer in the world. It consists of five aisles of HPE Cray Supercomputing EX4000 system cabinets, inside which are eight compute chassis, each with room for eight compute blades, eight HPE Slingshot switch blade slots, and one power/signal midplane.

Processing power for Lumi is provided by AMD and it contains almost 12,000 MI250x GPUs and 262,000 AMD Epyc Milan CPU cores. That doesn’t mean it’s operating as a single machine, though. There are eight partitions, each with a different specialty:

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

- LUMI-G: GPU partition, with 11,900 AMD Instinct MI250X GPUs

- LUMI-D: Data analytics, with graphics GPUs for analytics and data visualization

- LUMI-F: Accelerated storage. Using HPE Cray ClusterStor E1000 storage systems, it’s a 9PB flash-based storage layer with a read bandwidth of 3TB/s and extreme IOPS capability

- LUMI-P: 80PB parallel file system

- LUMI-O: Object storage with 30PB encrypted object storage for storing, sharing, and staging data

- LUMI-Q: Quantum processors

- LUMI-K: Container cloud service

- LUMI-C: A supplementary CPU partition with 262,000 AMD Epyc CPU cores

For customers that want to use more than one of these partitions, there’s also a high-speed interconnect using HPE Slingshot. This allows resources from several of the partitions to be used within a single run.

While Lumi’s outer casing is atmospherically lit, inside the room is bright and echoes with the noise of its servers and the infrastructure that keeps the supercomputer cool. It’s not completely deafening – although I picked up a pair of earplugs, others who were also on the tour chose not to and seemed to bear no ill effects.

Lumi's exterior, which sits within the shell of a former paper mill.

It would probably be a different story if Lumi were air-cooled, but the direct water cooling and what happens to it once it has passed through the system is part of what makes Lumi special.

Running clean

Lumi is one of the greenest supercomputers. When it came online in June 2022, it immediately took the number three spot in the Green500 list of the most energy-efficient supercomputers. It has since dropped down the rankings and in June 2024 – the most recent rankings at the time of publication – was sitting at number 12.

But this doesn’t tell the whole story. While like any supercomputer Lumi requires a huge amount of energy to run, it’s all sourced from a local hydroelectric power plant that predates it. This means that from an energy use point of view at least, Lumi is carbon neutral.

Another growing concern about large data centers and supercomputers is the amount of water they use. Frontier, the world’s fastest supercomputer, requires 6,000 gallons of water to run through its system per minute to keep it cool, according to Bloomberg.

As my co-host and I recently discussed on the ITPro Podcast, this water must be fresh with as few impurities as possible. This is having a major impact on water resources in some towns and cities around the world that are close to large data centers, particularly in more arid regions. Additionally, the water that has passed through the data center – be that a cloud computing facility, supercomputer, or proprietary – is hot. While it varies from facility to facility, the average is approximately 40ºC, which is the case for Lumi.

Once again, Lumi’s unique geographic location means its impact is far lower than that of a system located in many other regions. Finland is known as the “land of a thousand lakes” and that’s not just a boast from the Finnish tourism board – in fact, it’s something of an understatement.

There are actually 187,000 lakes in Finland, which according to World Atlas is enough for one lake per 26 Finns. In short, there’s plenty of fresh water to go around, and having a supercomputer nearby isn’t going to impact the amount of potable water available to the residents of Kajaani.

Lumi even contributes to another part of the city’s infrastructure. The 40ºC water it produces is fed into a local district heating boiler, which is conveniently located on the same industrial site. There it’s heated up further and distributed to domestic buildings in the city for heating during the winter months. While this may be a novel idea for people living outside the Nordics, in Finland it’s the most common form of heating, according to industry body Finnish Energy.

“There are some houses that are still directly electrically heated, like private houses, but virtually all apartments and even most of the houses [in Kajaani] are district heated,” Manninen tells me.

This is certainly beneficial for a city where average temperatures are between 1ºC and -11ºC for six months of the year – even in July the mercury rarely hits 20ºC. Eventually, some of this water once it has cooled on its journey around the city comes back to Lumi and the process starts again.

But wait, there’s more.

Even the building that houses the facility itself is recycled. The last roll of paper to be produced at the paper mill that once called the building home came off the production line in 2008 and the machines themselves were dismantled two years later.

It was another nine years before Lumi was built, but the fact no new concrete was poured to accommodate it lends another stripe to its environmentally friendly credentials, as well as those of Mahti and Phuti.

Putting science at the core

So what kind of workloads is this facility running? In the words of Katja Mankinen, a data scientist at CSC, “tons”.

“In Lumi, you can build everything, from the smallest scales [such as] simulating matter [and] particles, how they interact, what are their properties, to what happens in the universe at the galaxy scale,” Mankinen told the handful of assembled journalists.

“We also have projects that help more societal issues – how to cure cancer, how to create personalized medicine, how to help people who have health problems,” she added.

One of the most high-profile permanent residents is Destination Earth, an ambitious project that seeks to create a digital twin of the planet Earth. Currently, according to scientists at CSC, Destination Earth can model climate and extreme weather events with unprecedented accuracy. The official timeline for Destination Earth also includes unspecified “enhancements” by 2026, with the ultimate aim of a “full digital replica of the Earth” by 2030.

A storage cabinet for Destination Earth.

Outside Destination Earth, Manninen tells me that a little over 50% of CPU cycles are used for training neural networks. This could include large language models (LLMs) for example or, increasingly, generative AI.

One way that this 50% is being used is by researchers from the University of Turku in the southwest of Finland. They have trained LLMs in minority languages, starting with Finnish before moving on to other Nordic languages, as well as now English and code.

Manninen expands on this: “Commercial LLMs are getting better, but they're still not perfect and there’s only a small section of the parameters that are actually dedicated to these kinds of marginal languages, like Finnish.

“These are important initiatives, like national LLM projects that take place as academic initiatives,” he adds, while also pointing out that AMD is involved in another project to create an LLM that knows all the official languages of the European Union.

RELATED WHITEPAPER

The 50% not occupied by LLMs and generative AI is “pure high performance computing (HPC)”, Manninen says – floating point 64-bit workloads for physics, climate science, and so on.

“There’s also a niche – but a growing niche – in converged HPC and AI,” he says. “For example, there was a material science case where simulation data was being produced and then you train the [neural] network on the go as the actual production to replace simulations or speed up science. It’s still small, but it’s a growing percentage.”

Organizations wishing to use Lumi resources can apply through the official website, although there are stipulations around who can use it – it’s an EU initiative after all. However there are some benefits, not least that while organizations can keep the results of their research private if they choose to make them public then it’s “basically free to use”, says Mankinen. There’s also no need to move to Finland, let alone somewhere as distant as Kajaani, as everything can be done remotely.

The future

CSC’s future plans for Lumi are rather poetic, given its history as a factory.

Adjacent to the hall that holds Lumi is another almost identical room that once would have been filled with machinery for the paper mill but currently lies completely empty, save for a few wooden pallets and boxes. It seemed strange initially that we were shown this room on our tour, but as it turns out within the next few years it may be home to a new kind of factory.

Manninen told me that CSC hopes to host one of the EU’s AI Factories in this cavernous hall and that it is “well positioned” to do so. The call for expressions of interest went out on 10 September 2024 and continues until the end of the year.

This large, unused space could house vital AI infrastructure for the EU in the near future.

It should be some time in 2025 that the team looking after Lumi find out whether it’s time to call in the builders. Whether or not she gets a next door neighbor, though, the Queen of the North is still an example of how a technology that could have serious negative environmental impacts can be run in a more environmentally friendly way. While its location is somewhat unique in terms of its geography, infrastructure, and climate, there are surely more universal lessons that can be taken into future supercomputer builds elsewhere in the world.

Jane McCallion is Managing Editor of ITPro and ChannelPro, specializing in data centers, enterprise IT infrastructure, and cybersecurity. Before becoming Managing Editor, she held the role of Deputy Editor and, prior to that, Features Editor, managing a pool of freelance and internal writers, while continuing to specialize in enterprise IT infrastructure, and business strategy.

Prior to joining ITPro, Jane was a freelance business journalist writing as both Jane McCallion and Jane Bordenave for titles such as European CEO, World Finance, and Business Excellence Magazine.

-

Cleo attack victim list grows as Hertz confirms customer data stolen

Cleo attack victim list grows as Hertz confirms customer data stolenNews Hertz has confirmed it suffered a data breach as a result of the Cleo zero-day vulnerability in late 2024, with the car rental giant warning that customer data was stolen.

By Ross Kelly

-

Lateral moves in tech: Why leaders should support employee mobility

Lateral moves in tech: Why leaders should support employee mobilityIn-depth Encouraging staff to switch roles can have long-term benefits for skills in the tech sector

By Keri Allan

-

HPE eyes enterprise data sovereignty gains with Aruba Networking Central expansion

HPE eyes enterprise data sovereignty gains with Aruba Networking Central expansionNews HPE has announced a sweeping expansion of its Aruba Networking Central platform, offering users a raft of new features focused on driving security and data sovereignty.

By Ross Kelly

-

HPE unveils Mod Pod AI ‘data center-in-a-box’ at Nvidia GTC

HPE unveils Mod Pod AI ‘data center-in-a-box’ at Nvidia GTCNews Water-cooled containers will improve access to HPC and AI hardware, the company claimed

By Jane McCallion

-

‘Divorced from reality’: HPE slams DOJ over bid to block Juniper deal, claims move will benefit Cisco

‘Divorced from reality’: HPE slams DOJ over bid to block Juniper deal, claims move will benefit CiscoNews HPE has criticized the US Department of Justice's attempt to block its acquisition of Juniper Networks, claiming it will benefit competitors such as Cisco.

By Nicole Kobie

-

Supercomputing in the real world

Supercomputing in the real worldSupported Content From identifying diseases more accurately to simulating climate change and nuclear arsenals, supercomputers are pushing the boundaries of what we thought possible

By Rory Bathgate

-

HPE plans to "vigorously defend" Juniper Networks deal as DoJ files suit to block acquisition

HPE plans to "vigorously defend" Juniper Networks deal as DoJ files suit to block acquisitionNews The US Department of Justice (DoJ) has filed a suit against HPE over its proposed acquisition of Juniper Networks, citing competition concerns.

By Nicole Kobie

-

Discover the six superpowers of Dell PowerEdge servers

Discover the six superpowers of Dell PowerEdge serverswhitepaper Transforming your data center into a generator for hero-sized innovations and ideas.

By ITPro

-

HPE Discover Barcelona: What’s the business benefit of supercomputers?

HPE Discover Barcelona: What’s the business benefit of supercomputers?ITPro Podcast With potential in fields such as AI to scientific modelling, global interest in supercomputers continues to rise

By Jane McCallion

-

El Capitan powers up, becomes fastest supercomputer in the world

El Capitan powers up, becomes fastest supercomputer in the worldNews Earth’s newest supercomputer is fast, efficient, and its use cases are rather different

By Jane McCallion