Satellite broadband could turbocharge rural business connectivity

The burgeoning industry is pledging to succeed where fibre has failed, in a much-needed push to connect chronically underserved businesses

Satellite connectivity is undergoing a major expansion, benefiting from major investment from organisations such as SpaceX, OneWeb and DISH. SpaceX’s Starlink, for instance, now has more than 3,000 satellites in its constellation, while OneWeb has recently partnered with French satellite operator Eutelsat to boost its coverage. Public sector organisations, such as the EU and DARPA, are also getting in on the action, with the former set to launch a constellation this decade to serve Europe with 5G. The latter, meanwhile, has launched a competition to develop a satellite network to transmit encrypted communications.

Although the cost of launching a satellite may seem extortionate right now, when seen as part of a larger outlay that provides broad coverage, high investment might make sense. Each satellite can provide coverage for a very wide area, whereas fibre will never be able to reach every single customer; some businesses and households will always be too remote. Additionally, for areas lacking basic infrastructure, satellite deployments might arguably outpace the fastest cable laying operations.

The satellite broadband industry has jumped on this opportunity, and sees a great deal of potential in providing connectivity for difficult-to-reach customers, like people living on mountains or based in far-removed rural areas. Due to practical issues, and market forces, this customer base has traditionally suffered from unreliable coverage and slow speeds, while those based in major towns and cities have been able to get ahead.

Organisations like SpaceX, however, are hoping to be the remedy. Starlink, for instance, says its services provide internet for “remote and rural locations across the globe”, while OneWeb claims it “exists to remove the barriers to connectivity that are holding economies back”. The company highlights the widely publicised “digital divide” experienced by more than three billion people in rural and remote areas worldwide, pledging to bridge it in a way fibre optic cables haven’t yet been able to.

The dismal state of rural connectivity

Although cities seem like a natural home for major businesses, swathes of organisations operate in rural areas, with more employees than ever before also working from home on city outskirts or the countryside. Government figures show 23% of all registered businesses in England are based rurally (549,000), with remote areas host to more businesses per head than urban areas, excluding London.

RELATED RESOURCE

Can't choose between public and private cloud? You don't have to with IaaS

Enjoy a cloud-like experience with on-premises infrastructure

Last year, Three’s head of government affairs, Simon Miller, argued the government was underserving rural organisations, despite continued full-fibre rollout. Even rural areas with a range of connectivity options face reduced speeds, too, with 2020’s average speeds in rural England standing at 51 Mbits/sec versus the urban figure of 84 Mbits/sec. Some businesses even lack services as basic as reliable mobile phone signal, preventing them from engaging in digital transformation or performing tasks like video conferencing.

The status quo is hugely frustrating, Dave Happy, 5G RuralDorset spectrum standards & security lead, tells IT Pro. “I find it chronically depressing that, after the sharp end of 37 years of deregulation, that we're even still having the discussion at all,” he says. “The notion that a rural community should be settling for just coverage and not adequate connectivity speeds is itself a concept founded on shaking and shifting sands.

ChannelPro Newsletter

Stay up to date with the latest Channel industry news and analysis with our twice-weekly newsletter

“When you think about everybody now, using one-time pass codes for purchases online – I can’t, and 15% of the country, after 2025, may [still] have a similar problem. Is that the kind of world we want to live in? It’s a bigger failing and it could be addressed by policy decisions higher up, and I’d like to see a little bit more weight to those policy decisions.”

Could comprehensive satellite coverage alleviate these problems? Happy is quick to contest the claim satellite launches could provide coverage quicker than fibre for rural businesses, although low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites might play a role in future. He cites one provider that was deploying 50km of rural fibre a week, which has risen to nearly 70km. This organisation has four ploughs in operation and is directly burying the fibre.

Despite the ongoing rollout, though, communities not currently served by fibre optic cable can face quotes of tens of thousands of pounds to get lines brought out to them, or must wait until larger network operators see their area as profitable enough to recoup the cost. In comparison, satellite broadband customers can expect smaller setup and monthly fees — organisations in the United States, for instance, can get 350 MBits/sec for $500 per month, with a one-time setup fee of $2,500 through Starlink.

Ofcom’s role in spectrum allocation is key

In 2021, BT and OneWeb signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the intention of exploring LEO satellite communication for rural customers. This partnership will focus on improving capacity, mobile resilience, backhaul and building out coverage in challenging locations. The two firms will also consider ways to develop new services beyond the UK’s shores for BT’s global customers.

As things stand, the company expects high-altitude platform (HAP) systems to combine with LEO satellites, with the firm examining applications for LEO around resilience, such as backhaul backup in remote areas, according to a spokesperson. There are challenges, though, at play. Although LEO, on its own, offers a number of possibilities, there are capacity constraints that means it might not be practical in offering a ‘direct to customer’ option. Capacity constraints, specifically, could translate to spectrum rationing – particularly if Ofcom rules the increasingly crowded satellite market must directly compete with internet service providers (ISPs) for high-frequency millimetre wave (mmWave) bands above 24Ghz.

Little consensus has so far been reached over the rights of satellite operators within Europe. MmWave offers greater bandwidth and lower interference than other bands, which puts it in high demand for both satellite networking operators as well as for 5G usage by traditional network operators. Sharing issues, therefore, may occur above 40.5GHz, according to Aarti Holla-Maini, secretary general of the Global Satellite Operators Association (GSOA), which will mean requiring emission limits on 5G equipment. “We have urged Ofcom to ensure protection of satellite DL (40.5GHz – 42.5GHz) with separation distances, as well as protection of satellite UL (42.5GHz – 43.5GHz) satellite receivers from aggregate interference from 5G base stations.”

GSOA isn’t concerned allocation will necessitate spectrum rationing, with some groundwork having previously been laid. “This part of the band was foreseen for some years as a priority band for 5G by the EU anyway,” adds Holla-Maini. “But it’s potentially a deployment constraint because satellite operators will have to co-exist with 5G in urban areas, which might put constraints on where we can deploy gateway earth stations.”

Gateway earth stations are satellite dish hubs that send data from fibre networks to a constellation and to a user’s own receiver, and vice versa. They require adequate space, free of obstructions such as tall buildings or dramatic geographic features, as well as weather conditions conducive to good radio transmission – the same set of criteria required by telecoms infrastructure. Beyond interference caused by stations packed too closely, competition between operators could rear its head not through allocation, but the mundane problem of real estate on the ground. Urban areas could be particularly difficult to populate with infrastructure, both due to competition from existing 5G masts and reduced space.

Accessing untapped ultra-rural potential

While the debate over spectrum allocation rages on, rural businesses continue to suffer. Scotland, home to some of the leading lights of the UK tech sector, has stark differences in connectivity between cities and rural communities. “Scotland’s got some specific challenges – 98% of the land mass is classified as rural or ultra rural, which means that to start with they haven’t got the decent connectivity,” says Julie Snell, Scotland 5G Centre chair. “Trying to enable that has been a really big challenge, and the pandemic really brought it home.”

The Scottish government officially defines rural areas as “accessible” if they have a population of less than 3,000 within a 30 minute drive of a settlement containing 10,000 or more people, and either “remote” or “very remote” if the drive takes more than 30 mins. Snell notes there’s great potential among business in remote communities that isn’t currently being tapped, with 21% of the Scottish GDP coming from such rural areas, despite the fact they’re often poorly connected. Bridging the digital divide could hugely boost the economy.

RELATED RESOURCE

Can't choose between public and private cloud? You don't have to with IaaS

Enjoy a cloud-like experience with on-premises infrastructure

“Satellites have absolutely got to be part of the solution in Scotland, which has now got a huge space industry,” Snell continues. “We are looking at it, and not just for Scotland, but any other really remote areas. It isn’t always necessarily about 5G – it’s about the best connectivity you can get. In some cases, it’s never going to be reached by wireless, and it’s never going to be reached cost-effectively by a fibre link. There are times when it’s going to be satellite.”

It’s clear satellite broadband offers a compelling story that makes it sound an ideal solution for rural customers’ woes. After all, if one relies on the market, there will likely always be businesses whose premises are too far removed for network infrastructure providers to justify running fibre to, without huge setup costs being passed onto the end-user. For several good reasons, it may be some years before UK businesses can make full use of satellite broadband, but, when deployed and utilised correctly, LEO satellites could prove a powerful and permanent antidote for underserved rural business.

Rory Bathgate is Features and Multimedia Editor at ITPro, overseeing all in-depth content and case studies. He can also be found co-hosting the ITPro Podcast with Jane McCallion, swapping a keyboard for a microphone to discuss the latest learnings with thought leaders from across the tech sector.

In his free time, Rory enjoys photography, video editing, and good science fiction. After graduating from the University of Kent with a BA in English and American Literature, Rory undertook an MA in Eighteenth-Century Studies at King’s College London. He joined ITPro in 2022 as a graduate, following four years in student journalism. You can contact Rory at rory.bathgate@futurenet.com or on LinkedIn.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Why energy efficiency could be key to your business’ success

Why energy efficiency could be key to your business’ successSupported editorial An energy efficient data center setup can help save on bills, but the benefits don’t have to stop there

By ITPro Published

-

Digital Twins - Transforming supply chains and operations

Digital Twins - Transforming supply chains and operationsWhitepaper A virtual view of products, processes, and operations, as well as the impact of various factors on performance

By ITPro Published

-

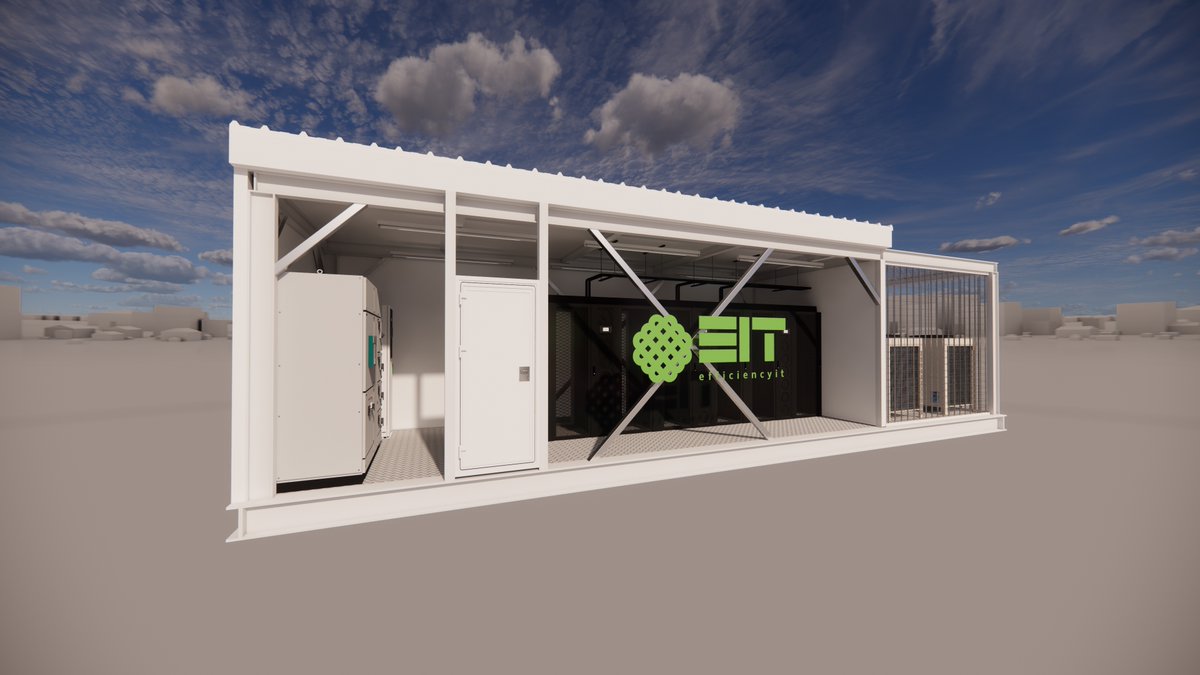

UK's EfficiencyIT launches prefabricated data centre offering

UK's EfficiencyIT launches prefabricated data centre offeringNews The company has previously built modular data centres for government and defence customers in 12-16 weeks

By Zach Marzouk Published

-

Equinix is growing data centre-powered fruit and veg

Equinix is growing data centre-powered fruit and vegNews The data centre company has installed a rooftop farm at one of its sites to make use of excess heat

By Zach Marzouk Published

-

Gov's broadband plans do little to address 'rural brain drain', expert warns

Gov's broadband plans do little to address 'rural brain drain', expert warnsNews Businesses are still unable to compete with urban counterparts, forcing job seekers into the cities and suppressing innovation

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Podcast transcript: The crisis in rural connectivity

Podcast transcript: The crisis in rural connectivityIT Pro Podcast Read the full transcript for this episode of the IT Pro Podcast

By IT Pro Published

-

The IT Pro Podcast: The crisis in rural connectivity

The IT Pro Podcast: The crisis in rural connectivityITPro Podcast Rural businesses are still being left behind and face shutdowns of 3G and copper without anything to fall back on

By IT Pro Published

-

Princeton Digital Group reveals "wise" $1 billion+ Indonesia data centre investment to service Singapore

Princeton Digital Group reveals "wise" $1 billion+ Indonesia data centre investment to service SingaporeNews The new investment will help customers located in Singapore expand their infrastructure

By Zach Marzouk Published