New tool masks your search habits from data harvesting ISPs

'Internet Noise' is able to flood your search history with junk terms to throw off snooping advertisers

Although the new US administration seems adamant to repeal a law which prevents ISPs from selling user data, that hasn't stopped said users from creating new ways to frustrate the process.

One person in particular has come up with a way of flooding an internet history with random Google searches, preventing ISPs from accurately profiling customers habits.

The website, which is dubbed "Internet Noise", acts like a signal jammer, throwing ISPs off the trail as they seek to sell user data to advertisers, or draw insights from the things you typically search for.

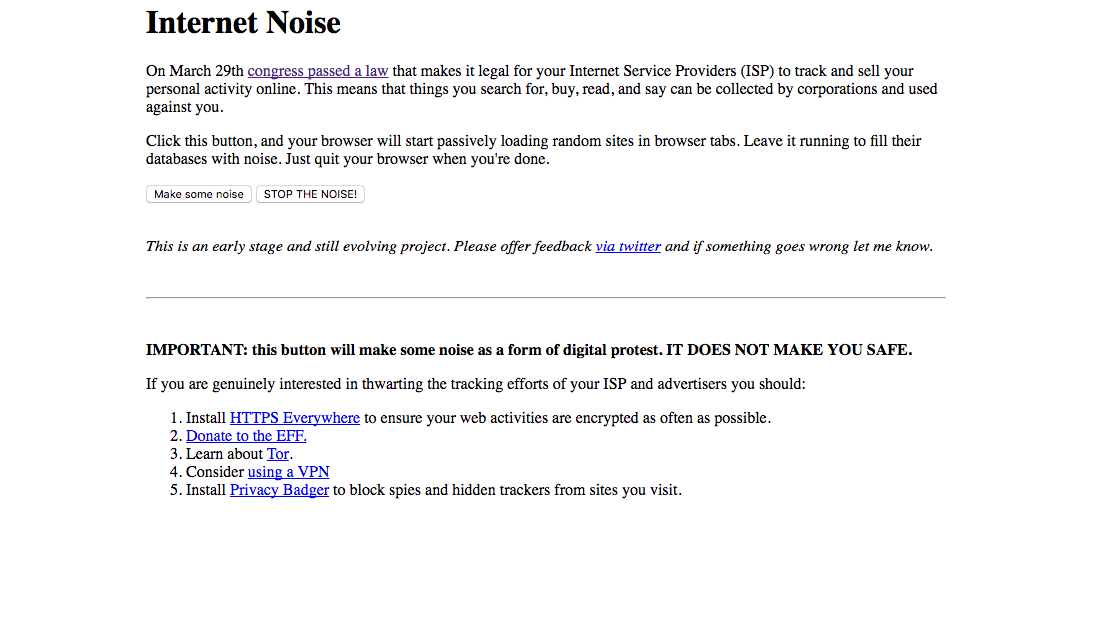

'Internet Noise' is still in development, currently hosted on github

"I cannot function in civil society in 2017 without an internet connection, and I have to go through an ISP to do that," said Dan Schultz, programmer and inventor of Internet Noise, speaking to Wired.

Schultz regards the tool, which is still in its early stages of development, as a "digital protest", but reminds users it does not encrypt their search traffic like a VPN might.

In order to frustrate ISPs, Schultz googled the "Top 4,000 nouns", creating a list of terms that is then used to randomly to open five new browser tabs when a user clicks "Make some noise".

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

The search is repeated every ten seconds, opening new search tabs each time. Within minutes a user's search history is awash with random LinkedIn, Pinterest, and Wikipedia searches about anything and everything. The automated website works in a similar way to the recently banned Google Chrome plugin Adnauseam.io, which randomly clicked on website adverts to disrupts the model of targeted advertising.

These sorts of tools are fairly rudimentary in their design, as any smart algorithm will be able to spot the random search terms as fake based on the short time the system stays on each page. But what they do represent is a growing feeling that if internet users are unable to prevent the harvesting of data for cash, they can at least make it as difficult as possible.

29/03/2017: Congress votes to roll back US internet privacy rules

The USA has come another step closer to removing privacy protections for residents of the country.

Overnight, the House of Representatives voted 215-205 in favour of repealing Federal Communications Commission (FCC) rules that prevent ISPs from selling their customers' data without their consent. Having passed through both houses of Congress, all that is required now is the president's signature.

The current FCC rule, which came into force just days before President Trump was voted into office, requires broadband providers to get their customers' express permission to sell certain types of data, and web records, to advertisers.

According to the Financial Times, the Internet and Television Association, the members of which include the USA's largest cable countries, said removing the regulation would "[restore] consumer privacy protections that apply consistently to all internet companies".

Dan Jaffe, a lobbyist for the Association of National Advertisers, said: "[The FCC regulation] would have created a very uneven playing field."

"Collecting information so you can provide consumers content that is relevant to them is of great value. There will be a great deal more spam if you cannot gather what we think is perfectly reasonable data," he added.

His comments were in line with a statement issued to both houses of Congress by six of the largest advertising and broadband trade groups, which warned the rule "would break well-accepted and functioning industry practices, chilling innovation and hurting the consumers [it] was supposed to protect".

President Trump now has 10 days, excluding Sundays, to sign the reversal into law.

24/03/2017: US Senate votes to allow ISPs to sell people's data without their consent

US internet service providers (ISPs) may soon no longer need people's explicit consent to sell or share their web browsing data or personal information with third parties.

The US Senate voted 50-48 to roll back rules instituted last October by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) that were designed to force ISPs and mobile carriers to gain consumers' opt-in consent to share their data with other companies.

The resolution, first proposed earlier this month by Republican senator Jeff Flake and co-sponsored by fellow Republicans, must now go through the House of Representatives in order to repeal the FCC's privacy legislation.

Republican senator John Thune said yesterday in the Senate: "As chairman of the commerce committee which has jurisdiction over the internet, I've worked hard to promote policies that encourage the private sector to invest in and grow the internet ecosystem as a whole.

"All of that is jeopardised, however, if government bureaucrats have the ability to overregulate the digital world. When it comes to over-regulating the internet, one need look no further than the Democrat-controlled FCC under President Obama."

The vote fell along party lines, with Democrat senator Edward Markey one vociferous opponent of the resolution.

He said: "The Republicans are saying to the American consuming public: 'you have no privacy'. If you're at home and you've got Comcast or Verizon, if you've got AT&T and they're gathering all this information about you as a broadband provider, every site you go to, everything you're doing, everything your children are doing - what they're saying as of tonight: 'no privacy, no privacy for your family'. Everything is out there to be captured by these big broadband barons."

In a joint statement responding to the vote, FCC commissioner Mignon Clyburn and FTC commissioner Terrell McSweeny said: "If signed by the President, this law would repeal the FCC's widely-supported broadband privacy framework, and eliminate the requirement that cable and broadband providers offer customers a choice before selling their sensitive, personal information.

"This legislation will frustrate the FCC's future efforts to protect the privacy of voice and broadband customers. It also creates a massive gap in consumer protection law as broadband and cable companies now have no discernible privacy requirements. This is the antithesis of putting #ConsumersFirst. The House must still consider this legislation. We hope they recognise the importance of consumer privacy and not undermine the ability of Americans to exercise control over their sensitive data."

That reference to "no discernable privacy requirements" is significant ISPs could opt to offer the least privacy protection possible, because that is the easiest way to do it.

However, consumers can keep hold of their data by paying for a VPN through which to access the internet, which hides their web activity even from their ISPs by encrypting users' activity so the ISP can't see it.

Marty P. Kamden, CMO of NordVPN, said: "Internet users should regularly delete cookies, install antivirus and anti-tracking software, and make sure not to enter personal passcodes and credit card information when using open Wi-Fi networks. The best known method to keep your information private and encrypted from ISPs is a VPN."

Renate Samson, CEO of UK-based privacy campaign group Big Brother Watch, told IT Pro that the vote comes at a time when all people must count themselves as "digital citizens".

She said: "We are all digital citizens now. In a world driven by data, where data loss, breach, hack or misuse are commonplace problems, all citizens must understand that protection of their data is as critical as the protection of their physical selves. Weakening people's right to control who can access, share or sell data is a huge step backwards in ensuring the safety, identity security and privacy of US citizens."

Dale Walker is a contributor specializing in cybersecurity, data protection, and IT regulations. He was the former managing editor at ITPro, as well as its sibling sites CloudPro and ChannelPro. He spent a number of years reporting for ITPro from numerous domestic and international events, including IBM, Red Hat, Google, and has been a regular reporter for Microsoft's various yearly showcases, including Ignite.

-

OpenAI's 'Skills in Codex' service aims to supercharge agent efficiency for developers

OpenAI's 'Skills in Codex' service aims to supercharge agent efficiency for developersNews The Skills in Codex service will provide users with a package of handy instructions and scripts to tweak and fine-tune agents for specific tasks.

-

Cloud infrastructure spending hit $102.6 billion in Q3 2025

Cloud infrastructure spending hit $102.6 billion in Q3 2025News Hyperscalers are increasingly offering platform-level capabilities that support multi-model deployment and the reliable operation of AI agents

-

EU lawmakers want to limit the use of ‘algorithmic management’ systems at work

EU lawmakers want to limit the use of ‘algorithmic management’ systems at workNews All workplace decisions should have human oversight and be transparent, fair, and safe, MEPs insist

-

Cyber pros say the buck stops with the board when it comes to security failings

Cyber pros say the buck stops with the board when it comes to security failingsNews Fines, sanctions, and even prosecution are all on the table when it comes to cyber failings, practitioners believe

-

Data (Use and Access) Act comes into force

Data (Use and Access) Act comes into forcenews Organizations will be required to have an effective data protection complaints procedure and fulfil new requirements for online services that children are likely to use

-

UK businesses patchy at complying with data privacy rules

UK businesses patchy at complying with data privacy rulesNews Companies need clear and well-defined data privacy strategies

-

Data privacy professionals are severely underfunded – and it’s only going to get worse

Data privacy professionals are severely underfunded – and it’s only going to get worseNews European data privacy professionals say they're short of cash, short of skilled staff, and stressed

-

Four years on, how's UK GDPR holding up?

Four years on, how's UK GDPR holding up?News While some SMBs are struggling, most have stepped up to the mark in terms of data governance policies

-

Multicloud data protection and recovery

Multicloud data protection and recoverywhitepaper Data is the lifeblood of every modern business, but what happens when your data is gone?

-

Intelligent data security and management

Intelligent data security and managementwhitepaper What will you do when ransomware hits you?