Scientists train an AI to spot Alzheimer’s disease six years before human diagnosis

Californian-based researchers hope the deep learning model can serve as a support tool for clinicians

Researchers have trained a deep learning algorithm to detect signs of Alzheimer's Disease in patients on average six years before the condition is diagnosed by a human physician.

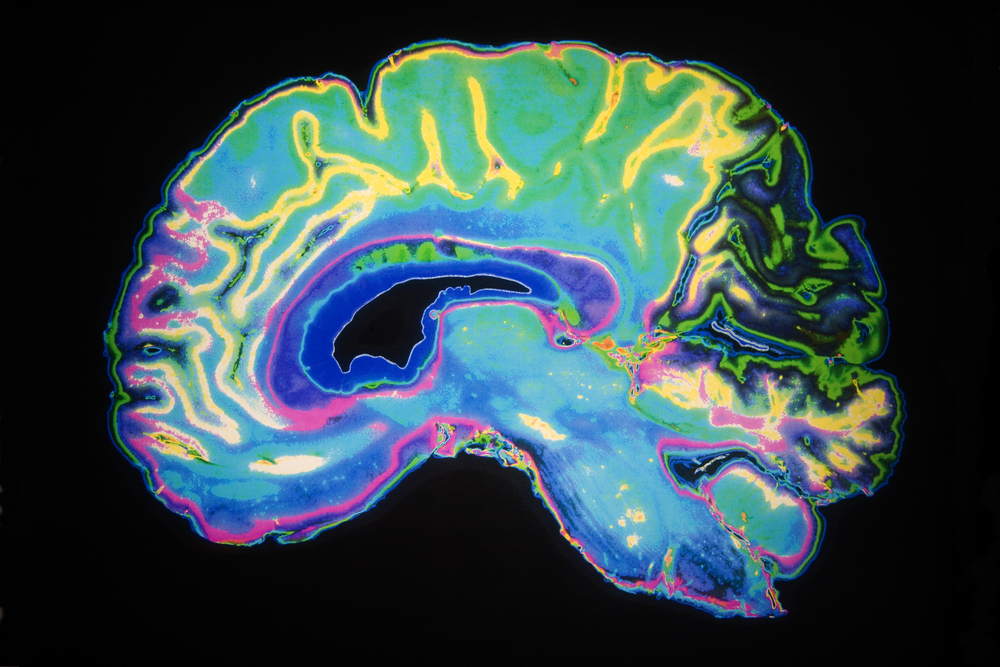

Californian-based scientists demonstrated that a neural network, once trained, was able to scan images of patients' brains and detect the presence of Alzheimer's on average 75.8 months prior to actual diagnosis.

The 20-strong team based their research on a modern diagnosis method, dubbed F-FDG PET (or fluorine 18 (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography), in which a radioactive glucose dye is passed through the brain, and photographed.

Specialists then examine and interpret these images using the naked eye for signs of Alzheimer's, a precursor known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or other related conditions across the spectrum.

Despite seeming time-consuming, this method has led to quicker and earlier diagnoses, and more effective treatments.

But given this method is reliant on pattern recognition, researchers saw it as an opportunity to vastly improve its performance by deploying a self-training AI algorithm, publishing their findings in Radiology.

"There is wide recognition that deep learning may assist in addressing the increasing complexity and volume of imaging data, as well as the varying expertise of trained imaging physicians," the team wrote.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

"The application of machine learning technology to complex patterns of findings, such as those found at functional PET imaging of the brain, is only beginning to be explored.

"We hypothesized that the deep learning algorithm could detect features or patterns that are not evident on standard clinical review of images and thereby improve the final diagnostic classification of individuals."

They set out to evaluate whether a deep learning algorithm could be trained to predict the final clinical diagnosis in patients who had undergone F-FDG PET, and how its success compared with current clinical standards.

From their study of 2,109 images from 1,002 patients who had already been diagnosed, they found their algorithm was able to detect Alzheimer's in images taken on average more than six years before diagnosis.

The algorithm performed better at recognising patients who would go on to have Alzheimer's than clinicians, as well as patients who would go on to develop neither Alzheimer's or its precursor MCI.

These findings are the latest in a series of studies and trials which show the potential power for AI to transform preventative healthcare and diagnosis.

In September the Francis Crick Institute revealed an AI learnt how to model and predict heart disease mortality rates in patients with a greater level of accuracy than trained doctors, or models created by experts.

Google's DeepMind AI project, meanwhile, reached an important milestone in the summer as its AI system was able to examine 3D images of the eye and diagnose sight-threatening conditions, as well as offer treatment advice, within seconds.

The algorithm, tested in conjunction with London-based Moorfields Eye Hospital, was able to recommend the best path of treatment for more than 50 eye diseases with 94% accuracy.

Despite bemoaning a handful of limiting factors, including a small sample size, the Californian researchers concluded that had developed a deep learning algorithm that can predict Alzheimer's "with high accuracy and robustness".

They added that with access to a much larger volume of data and opportunities to calibrate the model, the algorithm they developed could be integrated directly into the workflow of clinicians and serve as an essential support tool.

Keumars Afifi-Sabet is a writer and editor that specialises in public sector, cyber security, and cloud computing. He first joined ITPro as a staff writer in April 2018 and eventually became its Features Editor. Although a regular contributor to other tech sites in the past, these days you will find Keumars on LiveScience, where he runs its Technology section.

-

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?

Should AI PCs be part of your next hardware refresh?AI PCs are fast becoming a business staple and a surefire way to future-proof your business

By Bobby Hellard Published

-

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiatives

Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI launch brace of new channel initiativesNews Westcon-Comstor and Vectra AI have announced the launch of two new channel growth initiatives focused on the managed security service provider (MSSP) space and AWS Marketplace.

By Daniel Todd Published

-

Intel targets AI hardware dominance by 2025

Intel targets AI hardware dominance by 2025News The chip giant's diverse range of CPUs, GPUs, and AI accelerators complement its commitment to an open AI ecosystem

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Calls for AI models to be stored on Bitcoin gain traction

Calls for AI models to be stored on Bitcoin gain tractionNews AI model leakers are making moves to keep Meta's powerful large language model free, forever

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Why is big tech racing to partner with Nvidia for AI?

Why is big tech racing to partner with Nvidia for AI?Analysis The firm has cemented a place for itself in the AI economy with a wide range of partner announcements including Adobe and AWS

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Baidu unveils 'Ernie' AI, but can it compete with Western AI rivals?

Baidu unveils 'Ernie' AI, but can it compete with Western AI rivals?News Technical shortcomings failed to persuade investors, but the company's local dominance could carry it through the AI race

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

OpenAI announces multimodal GPT-4 promising “human-level performance”

OpenAI announces multimodal GPT-4 promising “human-level performance”News GPT-4 can process 24 languages better than competing LLMs can English, including GPT-3.5

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

ChatGPT vs chatbots: What’s the difference?

ChatGPT vs chatbots: What’s the difference?In-depth With ChatGPT making waves, businesses might question whether the technology is more sophisticated than existing chatbots and what difference it'll make to customer experience

By John Loeppky Published

-

Bing exceeds 100m daily users in AI-driven surge

Bing exceeds 100m daily users in AI-driven surgeNews A third of daily users are new to the past month, with Bing Chat interactions driving large chunks of traffic for Microsoft's long-overlooked search engine

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

OpenAI launches ChatGPT API for businesses at competitive price

OpenAI launches ChatGPT API for businesses at competitive priceNews Developers can now implement the popular AI model within their apps using a few lines of code

By Rory Bathgate Published