University College London's VR Lab pushes the future of virtual reality tech

Since 2000 UCL has used its VR cage to explore new ways to make virtual environments feel real

Some five years since the Kickstarter debut of the Oculus Rift, we now have access to all manner of VR headsets, ranging from the smartphone-powered basic Google Cardboard goggles to fully immersive headsets.

But whereas VR has been catapulted into the public eye of late, the technology in various guises has been around for some time, though not exactly in the form we would recognise today.

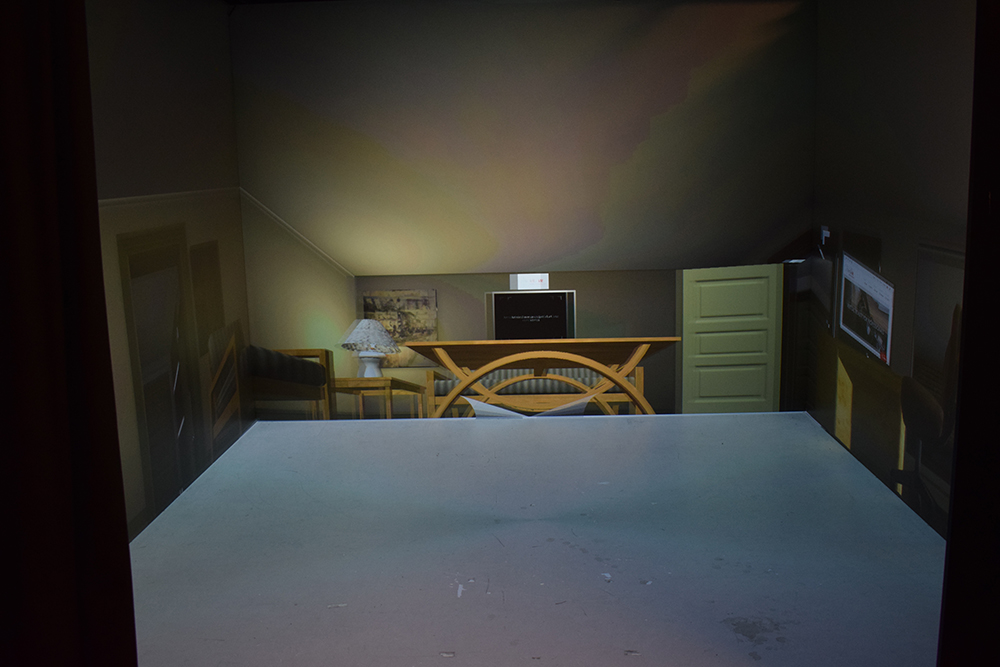

University College London has had a VR cave facility since 2000, offering a way for one or more people to immerse themselves in virtual environments without wearing heavy headsets.

And as one of the UK's top universities it has arguably been spearheading VR research for the some time.

Virtual exploration

"For a long time this was the only show in town if you wanted to do good VR simulation, albeit with fairly limited computer graphics," Dr David Swapp, research fellow and Immersive VR Lab manager at UCL's Department of Computer Science, tells IT Pro.

While technology consultancies and enterprises are actively exploring the business uses for VR, they are mostly working with headsets that are commercially available to anyone with deep enough pockets or a decent smartphone.

But Swapp and the lab are exploring VR for a more classic research point of view, looking at how it can be made more effective.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

"It's about understanding what makes it work. Virtual reality is all about sensory illusions, tricking people into thinking something that's not there is there," says Swapp.

"On a very mundane level it's projecting an image of something [for] you to interact with it, not necessarily believe it's real but act and behave as if it's real; that's a crucial element of [VR]."

This may seem simple, but the lab is doing a lot of interesting work that is not simply reliant on extracting more convincing visuals out of VR hardware but making virtual environments more believable and thus more effective in their use.

Immersive research

Swapp details an early experiment with the VR cage aimed at helping people with fears of public speaking. The simulation replicated a small crowd of people who could be programmed to be attentive or disruptive as needed.

Despite the lack of high fidelity graphics, Swapp explained the people attempting to deliver a talk found the experience to be very convincing.

Through learning how such VR experiences can be used and improved, that knowledge will filter down to the development of VR hardware and applications which will inevitably lead to improved technology for businesses to put to use.

The potential for VR to be used in all manner of businesses and industries is significant as well, if the other work the lab carries out is anything to go by.

"The way we've worked tends to have been through collaborations. The idea would be we'd work with scientists who are trying to solve some kind of problem using VR and we would use this study to advance our own knowledge of how well VR works," said Swapp, detailing an experiment designed to test the bystander effect.

Working with psychologists the lab was used to test how people react to an aggressive situation unfolding in front of them; do they get involved or stay out of it?

Swapp said testing had previously been limited to questionnaires but in the VR cage the bystander effect could be safely simulated, resulting in more realistic results for the psychology researchers and feeding the lab's knowledge of how effective its simulations are.

In the early days of the lab, there was a lot of focus on creating effective visual illusions and establishing tolerances, such as finding out how accurate movement tracking needs to be.

Swapp notes these issues still exist but as the technology has advanced, they become less of a critical issue. The goal now is on making simulations feel real and induce a feeling of presence to track "the degree to which you feel that you are inhabiting the virtual world as opposed to standing in a lab looking at projections".

"Ideally we want people to be unencumbered, not have to wear lots of equipment, and if they don't notice the technology supporting the illusion, that's great," highlights Swapp.

"My informal measure of that in here is how often people walk into the screens; if people walk into the screens we think 'fantastic it's working really well, hope they didn't hurt themselves!'."

Beyond visual illusions

The lab's current studies are looking at tackling how other senses work in VR, such as hearing audio in virtual environments, something which can be neglected in large projects. Audio is an important factor if people are to respond to something as if it's real even though their eyes are taking in less than photo-realistic graphics.

"At the end of the day it all comes down to sensory tricks. Some of the best discoveries in VR have been ways to fool our senses or see what you can get away with," says Swapp.

"One of the big projects we are involved in now is taking a look at multi-sensory and collaborative VR over very low-latency networks.

"One of the big foci of this project is haptic interaction, touch interaction, and this is a bigger element in a number of spheres industrially, whether it's teleoperation or just telepresence.

"Haptics are not very tolerant to delay for a number of reasons; you need to have very, very high update rates, otherwise our solid virtual surfaces feel spongy. If you're trying to interact remotely with somebody - the classic example is the virtual handshake - you can't do it with delay because you're just not quite in the right place at the right time.

"So we've been given access to some of the experimental network infrastructure that's all optical, very, very low latency where we can experiment with [haptics and latency], and we're doing this with the University of Liverpool; that's where our testbed is going to extend to."

Again, the work here will lead to the evolution of VR technology and its effectiveness as a whole, given UK university grants are now only awarded if they can prove a societal or industrial impact.

So while the VR Lab isn't working in any projects that will directly yield a Google-branded VR platform, for example, a lot of the work will filter into the VR sector as it matures.

Swapp notes those companies that are truly interested in VR saw the potential of it relatively early, leading to the likes of Jaguar Land Rover to hurry off and build their own VR cages to aid product and project design.

"When we first looked for industrial collaborators because we just built a cave and it was very exciting, the people who were really serious about [VR tech] went off and built their own ones," he explains.

However, Swapp said there is a 2020 grant that will look to open up the cave for European SMBs and universities to carry out work and experiments without incurring the hefty expense of making their own VR caves for potentially one-off projects.

This could sow the seeds for follow-up VR research and see the technology and its adoption spread.

With a lab festooned with VR headsets, a VR cave, haptic arms, and telepresence robots, UCL's VR Lab is clearly not being browbeaten by the idea that VR is and always will be a niche area.

Rather the lasting impression is one that there is a lot more to be seen from the immersive technology in terms of hardware, software and techniques to make virtual simulations feel less like thin illusions and more like real environments.

While limits still exist, Swapp is quietly confident there is a lot more potential to VR than ever before, and research and innovation will pave the way.

"I've lived through a number of cycles of hype and disappointment in VR and there was always a sense with this last wave, which started two or three years ago now, that this might actually get some traction this time," he concludes. "And it seems to be panning out that way."

Main image credit: Shutterstock. All other images: Roland Moore-Colyer

Roland is a passionate newshound whose journalism training initially involved a broadcast specialism, but he’s since found his home in breaking news stories online and in print.

He held a freelance news editor position at ITPro for a number of years after his lengthy stint writing news, analysis, features, and columns for The Inquirer, V3, and Computing. He was also the news editor at Silicon UK before joining Tom’s Guide in April 2020 where he started as the UK Editor and now assumes the role of Managing Editor of News.

Roland’s career has seen him develop expertise in both consumer and business technology, and during his freelance days, he dabbled in the world of automotive and gaming journalism, too.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Has Lenovo found the ultimate business use case for smart glasses?

Has Lenovo found the ultimate business use case for smart glasses?Opinion Lenovo’s T1 smart glasses offer a virtual desktop that only you can see

By Bobby Hellard Published

-

Virtual striker: Using VR to train Premier League stars

Virtual striker: Using VR to train Premier League starsCase Studies How one company is taking VR out of the boardroom and into the locker room

By Adam Shepherd Published

-

NeuPath and Cynergi will bring VR therapy to chronic pain management

NeuPath and Cynergi will bring VR therapy to chronic pain managementNews NeuPath will integrate Cynergi’s VR program with its remote pain management platform

By Praharsha Anand Published

-

HTC Vive Focus 3 review: The future of VR is here

HTC Vive Focus 3 review: The future of VR is hereReviews This smart and stylish headset is a leap forward for the technology

By Adam Shepherd Published

-

The IT Pro Podcast: Can VR unite the hybrid workplace?

The IT Pro Podcast: Can VR unite the hybrid workplace?IT Pro Podcast How one company is using virtual reality to bring its staff together

By IT Pro Published

-

HTC launches new business-focused VR headsets

HTC launches new business-focused VR headsetsNews Vive Pro 2 and Vive Focus 3 include 5K resolution, larger field of view, and business management tools

By Adam Shepherd Published

-

The IT Pro Podcast: Will VR ever be mainstream?

The IT Pro Podcast: Will VR ever be mainstream?IT Pro Podcast Despite years of development, VR is still a niche technology

By IT Pro Published

-

IT Pro Live: How virtual reality will power Workplace 2.0

IT Pro Live: How virtual reality will power Workplace 2.0Video The office of the future might not be a physical office at all

By IT Pro Published