How a mosquito bite inspired a campaign to map every school in the world

UNICEF turns to open source to highlight areas with disconnected schools and chronically underdeveloped infrastructure

In early 2015 the Zika virus emerged from the jungles of Brazil and quickly engulfed the vast majority of the South American continent and parts of the US and Mexico.

The disease, which spread primarily through mosquito bites but also transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, sparked international alarm due to the threat of microcephaly and other similar defects in newborn children.

By mid-2016, the World Health Organisation had declared the Zika virus a global public health emergency, with hundreds of thousands of people thought to have been affected across 90 different countries and territories.

The disease proved to be a wakeup call to a chronic lack of even basic medical infrastructure across Latin America. There were no vaccines available, no clinics prepared for the influx of concerned mothers, very few universal family planning services in place, and the high degree of poverty in the regions left many unable to access the most basic of protections, such as mosquito nets.

For organisations like UNICEF, the most immediate challenge was a lack of accurate data on those affected. Without official public records, the organisation was forced to rely on the region's mobile operators that were able to offer data, albeit aggregated and anonymised, on the movements of people. Combined with temperature and poverty data, which showed the most favourable areas for mosquitoes to breed, the information was used to help direct people away from the most dangerous areas.

School Mapping Project

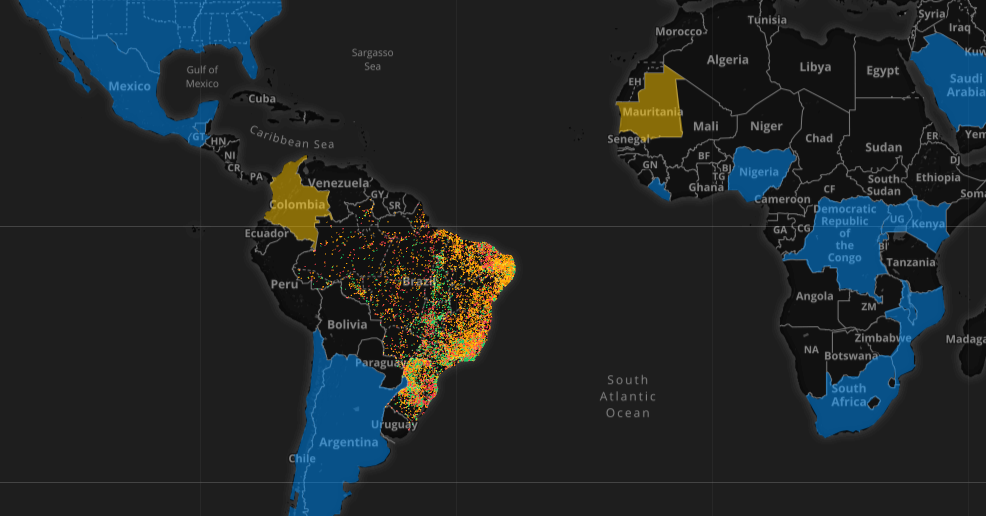

It was this experience of combining multiple data sets that inspired UNICEF to expand its data analysis approach to other areas of humanitarian concern. Chief among these projects was the creation of a tool that would map every school in South America, data for which had, until then, been either missing or alarmingly inaccurate.

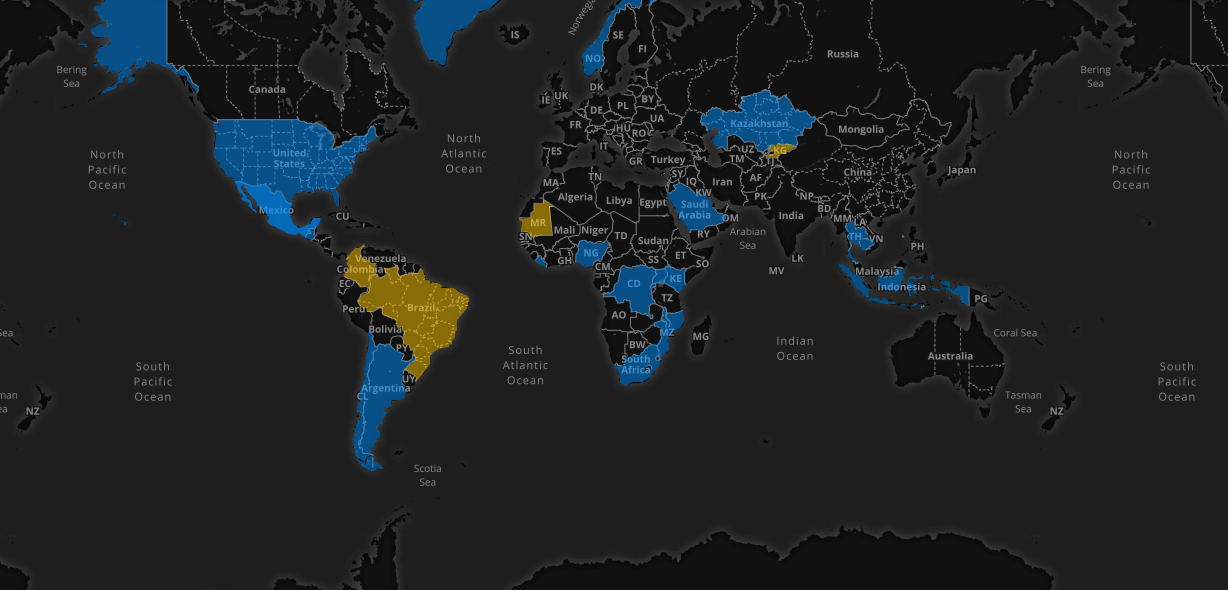

UNICEF's School Mapping Project covers 22 regions, although comprehensive data is only available in three (yellow)

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

"We work in 190 countries and those countries all have challenges that they're trying to address," says Erica Kochi, co-founder of UNICEF's Innovation unit. "In this particular case we were talking to countries in Latin America they're coming out of decades of civil war and they want to know where their schools are so they can connect them all and get them prepared for if a natural disaster happens or some sort of emergency."

"Still to this day in many countries around the world, the way information is gotten is that someone goes around with a piece of paper and they fill out a survey household to household," she explains. This information is often illegible, and hastily transcribed into Excel spreadsheets and passed up the chain to central offices. This faulty, incomplete data typically sits for six months before being analysed.

UNICEF's new School Mapping Project addresses gaps in public data in countries that have little to no information on the schools in their regions, including how connected they are to the outside world.

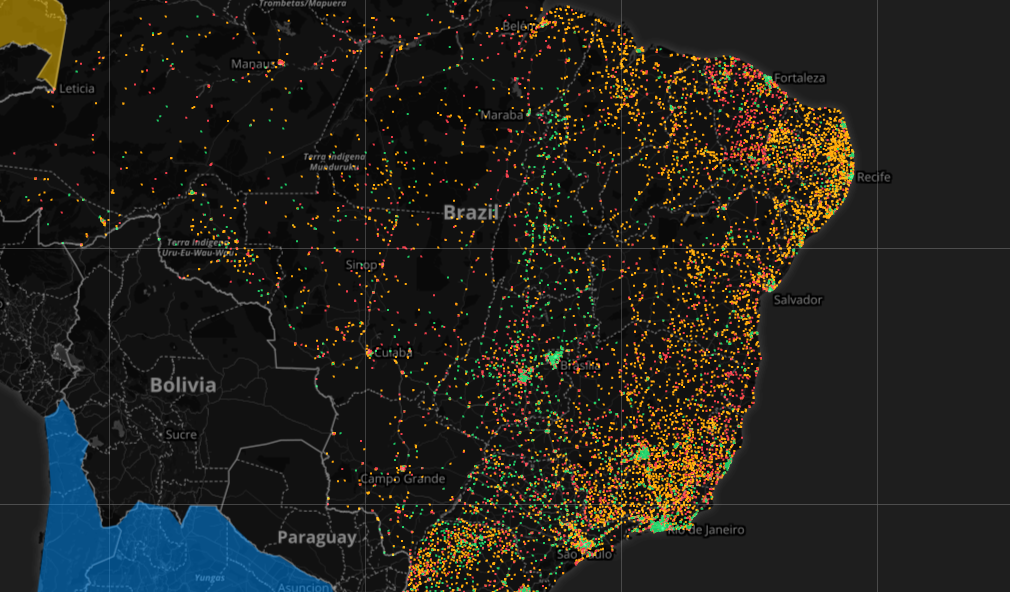

One overlay represents the quality of school internet connections, from fast (green) to no connection (red)

"Without information about how children are impacted by something, or where children are receiving education or not, clean water, and being able to measure those kinds of things, it's really hard to make an argument to a government about why they should be investing in that particular area or community," says Kochi.

"Also without measurement, it's really hard to see progress and to have progress. Because usually the terrible things will be swept under the carpet unless you bring them out into the light."

UNICEF embarked on the mammoth task of sourcing and pooling various datasets together, including those on population figures, poverty, infrastructure, geolocation and satellite imagery.

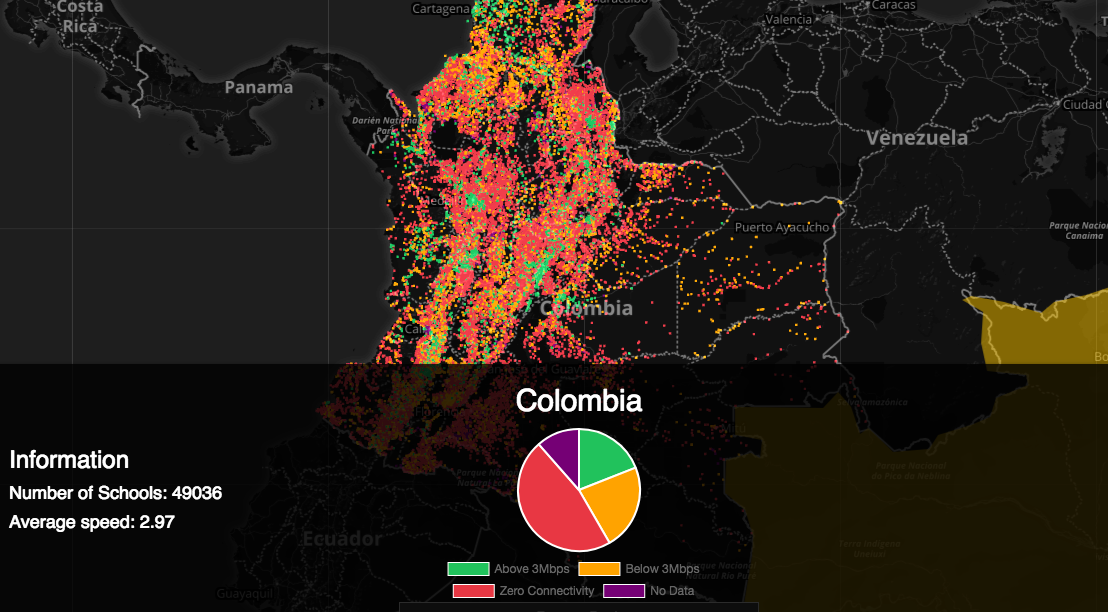

For example, data collected in Colombia has allowed UNICEF to see which of the region's schools have internet access, and the quality of any such connections. This has formed the basis of recommendations to the Colombian government on what areas are likely to be most at risk of being isolated during a national emergency.

The data found that the majority of schools in Colombia have no access to the internet

Supporting those that want to help

A great deal of the work on the School Mapping Project had already been done, however, what UNICEF really wanted was to provide was a means for other organisations, countries, academic groups and volunteers to contribute to the project on a permanent basis. For this, it turned to open source giant Red Hat.

"What we did with Red Hat was really look at different sources of data to get a really good understanding of what was happening on the ground, and where we should be focusing our very limited resources," explains Kochi.

UNICEF typically receives a sudden outpouring of support following a natural disaster or emergency, but has historically been unable to support this technically with a system capable of exploiting the available expertise. It was this that led UNICEF to embark on the creation of an entirely open source platform that could pull together global expertise to help manage and interpret data essentially a collaborative sandbox for those wanting to help.

"When we arrived at UNICEF we met brilliant data scientists that were really passionate about what they were doing," says Mike Walker, global director of Red Hat's Open Innovation Labs.

"This was brilliant, impactful work. But oh my gosh, talk about limited resources... a really small team of folks running the infrastructure, operations, application development, and also its an ecosystem where people come and go. So we were able to work with interns part-time and full-time employees, and contractors. It felt like an open source community to us."

Founded in 2016, Red Hat's Open Innovation Labs offers support to those wanting to fast-track open source projects. For an organisation like UNICEF, which Kochi admits has become far more discerning about what companies it chooses to work with, preferring shorter contract work over long-term partnerships, it offered an ideal way to expand on the project.

The development sprint

The residency programme allows companies to work directly with a dedicated team of Red Hat engineers over a one to three-month programme of intense workshops, culminating in a 'demo day' where a working prototype will be showcased.

"One of the toughest challenges was that data isn't perfect," says Walker. "We might be getting faulty data, and we did have that. So we created a data pipeline so that we could adjust new sources whatever they may be, and then make it easy to clean them. We focused on creating easy ways for partners to provide data securely, and ensure that the data remains in a place that's secure."

"We established a place that formed a residency that wasn't in either one of our offices and very intently focused on the problem we wanted to solve without distraction. It created an intense environment because there was so much focus and you can't get away from each other that was a very good thing," says Walker.

The goal of the eight-week residency was to build new capabilities on top of UNICEF's existing software platform known as Magic Box. Using Magic Box as a base layer to provide data sources, UNICEF essentially rebuilt its platform from the ground up on Red Hat's OpenShift the company's entirely free and open source cloud-based platform.

New systems like more robust delivery pipelines to ensure data is constantly available, the introduction of APIs, and virtualisation means it's now far easier for the platform to be tweaked and developed further by a collection of disparate developers across the world.

The finished product allows UNICEF and those that contribute to glean a complete picture of what's happening on the ground and make recommendations to local authorities on where their attention should be directed.

The project is also able to tap into real-time data and satellite imagery from both public and private bodies, providing information to charity and disaster relief organisations working to mitigate local disasters.

Importantly, this online sandbox supports contributions from those wishing to help, whether that's on a permanent or temporary basis.

Built to last

"Our objective was to improve the ability for community members to participate, whether they be interns or employees or whatever," says Walker. "You can have an impact by picking out a small piece of work, and more immediately see the results of your efforts. After we're gone we want to make sure you're able to build a community that can contribute more easily to a solution, years later."

With the platform now in place, Kochi explains that work is being done to build similar projects across the world where data is otherwise almost impossible to source, as well as expand the reach of the School Mapping Project as wide as possible.

"We're doing a project in Iraq around looking at nutrition and agriculture because if you have crops that fail you often have a nutritional crisis in a country," says Kochi. "Each of these [projects] are building on each other, and each involves many different partners. So it's absolutely critical that they are allowed to participate."

"At UNICEF we are at the beginning of our data science adventure," adds Kochi. "This is an ongoing project within UNICEF - but it's still a new research project, so it's not like every country in the world is using it. Integration into larger organisations takes time."

An alpha version of the School Mapping Project can be accessed here.

Dale Walker is a contributor specializing in cybersecurity, data protection, and IT regulations. He was the former managing editor at ITPro, as well as its sibling sites CloudPro and ChannelPro. He spent a number of years reporting for ITPro from numerous domestic and international events, including IBM, Red Hat, Google, and has been a regular reporter for Microsoft's various yearly showcases, including Ignite.

-

Meta just revived plans to train AI models using European user data

Meta just revived plans to train AI models using European user dataNews Meta has confirmed plans to train AI models using European users’ public content and conversations with its Meta AI chatbot.

By Nicole Kobie

-

AI is helping bad bots take over the internet

AI is helping bad bots take over the internetNews Automated bot traffic has surpassed human activity for the first time in a decade, according to Imperva

By Bobby Hellard