What is ransomware?

This type of malware could hit you hard in the pocket

Ransomware is one of the biggest cyber security threats facing businesses today. It's a type of malware that attackers can use to lock a device or encrypt its contents in order to extort money from the owner or operator.

The most popular ransomware strains targeting UK businesses Best ransomware removal tools How to beat ransomware

Given its potential to deliver a high return on investment, and the relative ease at which it can spread, this type of attack has become extremely popular among cyber criminals. It was recently named the biggest threat facing small-to-medium-sized businesses (SMBs) as attackers take advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic to attack employees outside of the office.

According to figures from cloud cyber security company Datto, 59% of MSPs said a shift to remote working had resulted in increased ransomware attacks, and 60% reported that their SMB clients had been hit by ransomware in the third quarter of last year.

How ransomware works

Ransomware infections typically appear after hackers fool users into downloading malicious applications, or attachments from phishing emails, in accordance with the general distribution of malware. This prompts scripts to run on a victim’s system that begins the process of downloading a payload, eventually leading to the confiscation of victims’ data, and locking them out of their systems.

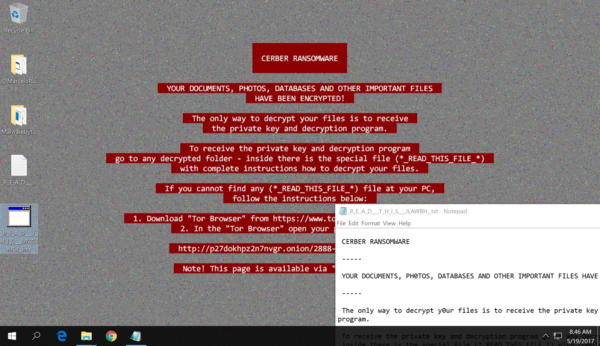

Attackers normally engage in ransomware attacks while trying to remain hidden from any cyber security measures protecting a system, encrypting files at a gradual pace in order to avoid raising any alarms. Unlike other kinds of malware, ransomware then alerts users to the fact that they’ve been attacked, usually with a message demanding a fee, or ransom, in order to grant access to the data they’ve stolen.

The wording of these messages varies from group to group but, generally, victims are first told that their files have been locked, before the hackers issue a threat, as well as a figure they must repay within a certain period of time.

The splash screen associated with the Cerber ransomware

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Many messages tend to be oddly friendly, treating the attack as a sort of conventional business transaction, while others are overly aggressive and threatening in nature. The Jigsaw ransomware strain is an example of one that attempts to push victims into paying the fee as quickly as possible, given it deletes one file for each hour no fee is paid. Then, should the user try to reboot the system, the ransomware strain deletes 1,000 files.

RELATED RESOURCE

The business guide to ransomware

Everything you need to know to keep your company afloat

The first attempt at ransomware emerged in 1989 with the ‘AIDS Trojan’, which encrypted the name of files rather than the content of files. The decryption key was also hidden in the strain’s code, meaning that cyber security professionals were able to remedy the situation without much fuss. Putting aside these errors, it represented the first case of a cyber criminal demanding payment in exchange for data they’d seized.

Attackers still operate under the same core principles, but are usually far more effective, and more often than not demand payment not in physical currency, but in cryptocurrencies. Most attackers favour Bitcoin or Monero, which are inherently difficult to trace.

Ransomware's evolution in 2020

Hundreds of ransomware strains are in deployment across the globe and tend to be specific to geography, so the biggest threat to your business normally depends on where you’re based. Last year, we examined the latest strains attacking UK organisations, finding the situation can differ vastly between regions.

Ryuk, for example, is prevalent in North America, for example, but relatively scarce in Latin America. Nevertheless, it’s one of the most popular strains, and figures show it accounted for a third of all ransomware incidents in 2020, numbering roughly 67 million. This is according to research by SonicWall. There are several high-profile attacks that made headlines, too, including one against French IT services giant Sopra Steria.

Another active strain, known as Maze, has recently been deployed to attack the critical systems of major technology firms including Canon in August 2020 and Xerox in July. The gang behind the strain revealed it was shutting down its operations for good towards the end of the year, however.

RELATED RESOURCE

The truth about ransomware

Data-stealing malware can bring the biggest business to its knees – but what is the real ransomware risk, and how do you safeguard against it?

FREE DOWNLOAD

Beyond particular strains prevalent in the wild, a handful of groups are also offered to cyber criminals for hire through the ransomware as a service business model. This involves criminals hiring hackers to plan and execute ransomware deployment against specific targets - which allows some to attack organisations without easily being traced, or without even needing to have any great depth of technical knowledge. Overall, it lowers the barrier to entry to cyber crime, meaning it’s much easier to launch a sophisticated and crippling attack should you have the cash and the will.

According to the Beazley Breach Response team, there was a 105% year-over-year increase in the number of ransomware attacks against businesses in Q1 of 2019. The same report found that the average ransomware demand has also increased by 93% to $224,871, although this has been skewed somewhat by a small number of large payouts.

However, large payouts are quickly becoming normal, as ransomware has started to shift its focus to larger organisations or critical public services. For example, two towns in Florida agreed to pay collectively $1.1 million to regain access to their systems following a widespread public sector ransomware attack.

Should I pay the ransom?

By design, ransomware is incredibly disruptive for businesses, and it can be tempting to take the quick way out and submit to demands – after all, every minute your business is offline, the greater the financial and reputational damage might be.

However, most experts agree that paying a ransomware demand is the worst thing you can do. Ransomware has become incredibly lucrative, with 121 million attacks recorded in the first half of last year alone, up 20% over the previous year. This is entirely fuelled by the shakedown of its victims, and the more that businesses give in to demands, even if the price is relatively low, the more hackers are going to use this tactic.

Even if you don’t buy into that idea of the greater good, there’s ultimately no guarantee that hackers will uphold their end of the bargain. Of course, it’s in a hacker’s own interests to do so, as victims will be unwilling to hand over their cash if they think their attackers will split and run, but there’s nothing to prevent them from deleting data once they get their money.

Unfortunately, in many cases, data encrypted by ransomware is best thought of as lost. How damaging that will be for your business will depend on how robust your data backups and recovery processes are. With a strong disaster recovery plan in place, it’s possible to take the sting out of a ransomware attack as soon as it starts.

RELATED RESOURCE

6 best practices for escaping ransomware

A complete guide to tackling ransomware attacks

Ransomware glossary

While ransomware itself might be fairly self-explanatory, there are going to be a handful of terms associated with the phenomenon that you'll encounter too.

Payload: The payload is the aspect of a malware strain that is responsible for the main infection of a victim's device. With regards to ransomware, the payload will be the malicious file that triggers the encryption process.

Backdoor: Caused by malware, a backdoor is used to describe a malicious entity that grants hackers remote access to a victim's device. This is usually installed on a machine as a result of a payload being delivered and guarantees access for data exfiltration, or the delivery of other payloads, such as ransomware.

Crypto-ransomware: In ransomware, encryption occurs following a successful infection. There are certain strains, known as crypto-ransomware, that deploy advanced and complex algorithms to encrypt data saved locally on a device. Often, operators will demand a ransom to be paid for decrypting the victim's hard drive.

WannaCry: Considered one of the most devastating cyber attacks of modern history, WannaCry was a form of self-spreading crypto-ransomware that led to an epidemic when it began to propagate between outdated Windows machines. Read more on WannaCry here.

2017 NHS ransomware attack

Perhaps the most famous ransomware attack to hit the UK happened on 11 May 2017, when the NHS and a number of large organisations in England and Scotland were hit by WannaCry. This strain is thought to have quietly spread across Europe, infecting major organisations including Telefonica in Spain, Deutsche Bahn in Germany, Renault and FedEx, before activating. It's believed hundreds of thousands of computer systems across 99 countries were affected.

The infection spread through three vectors. The initial payload (i.e. the ransomware software known as WannaCry or WannaCrypt) was brought into the organisations' network via a phishing email, with a user clicking on a malicious link or downloading a malicious file.

The infection then spread rapidly through the network using two tools thought to have been developed by the NSA the EternalBlue exploit and DoublePulsar backdoor which were released into the wild by the ShadowBrokers hacking group along with a number of other cyber weapons.

All the infected computers on the network consequently had their files encrypted with a ransom message displayed on their screen demanding of around $300 in Bitcoin to be paid within three days or $600 within seven days. It's unclear how many organisations paid, but by Monday 15 May, the cyber criminals had made over $40,000 according to the URLs associated with the ransom demands.

Microsoft had released a patch for the vulnerability, which affected all Windows operating systems from Windows 7 through to 8.1, back in March. However, it hadn't been applied to all elements of the affected organisations' network. There are several reasons this may have occurred, including the need for organisations to carry out a staged roll-out and potential conflicts with other critical systems and software.

Another reason is that many organisations still run Windows XP, once again usually due to compatibility issues. As XP is out of support, no patch for it was released in March, leaving all systems running it vulnerable to this attack. 90% of the NHS' IT estate was known to be running Windows XP at the beginning of 2017, with its custom support contract having been terminated in 2015.

Given the magnitude of the attack, however, Microsoft did create and issue a patch for XP but advised that organisations and individuals should always apply the latest software updates as soon as possible to protect against threats of this kind.

Dale Walker is a contributor specializing in cybersecurity, data protection, and IT regulations. He was the former managing editor at ITPro, as well as its sibling sites CloudPro and ChannelPro. He spent a number of years reporting for ITPro from numerous domestic and international events, including IBM, Red Hat, Google, and has been a regular reporter for Microsoft's various yearly showcases, including Ignite.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

‘Phishing kits are a force multiplier': Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25 – and experts warn it’s lowering the barrier of entry for amateur hackers

‘Phishing kits are a force multiplier': Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25 – and experts warn it’s lowering the barrier of entry for amateur hackersNews Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Healthcare systems are rife with exploits — and ransomware gangs have noticed

Healthcare systems are rife with exploits — and ransomware gangs have noticedNews Nearly nine-in-ten healthcare organizations have medical devices that are vulnerable to exploits, and ransomware groups are taking notice.

By Nicole Kobie Published

-

Alleged LockBit developer extradited to the US

Alleged LockBit developer extradited to the USNews A Russian-Israeli man has been extradited to the US amid accusations of being a key LockBit ransomware developer.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

February was the worst month on record for ransomware attacks – and one threat group had a field day

February was the worst month on record for ransomware attacks – and one threat group had a field dayNews February 2025 was the worst month on record for the number of ransomware attacks, according to new research from Bitdefender.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

CISA issues warning over Medusa ransomware after 300 victims from critical sectors impacted

CISA issues warning over Medusa ransomware after 300 victims from critical sectors impactedNews The Medusa ransomware as a Service operation compromised twice as many organizations at the start of 2025 compared to 2024

By Solomon Klappholz Published

-

300 days under the radar: How Volt Typhoon eluded detection in the US electric grid for nearly a year

300 days under the radar: How Volt Typhoon eluded detection in the US electric grid for nearly a yearAnalysis Lengthy OT lifespans give attackers time to penetrate networks underpinning critical infrastructure and plan future disruption

By Solomon Klappholz Published

-

Warning issued over prolific 'Ghost' ransomware group

Warning issued over prolific 'Ghost' ransomware groupNews The Ghost ransomware group is known to act fast and exploit vulnerabilities in public-facing appliances

By Solomon Klappholz Published

-

The Zservers takedown is another big win for law enforcement

The Zservers takedown is another big win for law enforcementNews LockBit has been dealt another blow by law enforcement after Dutch police took 127 of its servers offline

By Solomon Klappholz Published