Immunity passports: What do we really know about the ‘risk-free certificate’?

Proponents say they’re a gateway to reopening the country post-lockdown, but could they be a Pandora’s box of sensitive data?

You are standing in a queue for passport control. One by one, the people in front of you pass through the gates. You shift your weight from one foot to the other, pause the podcast you’re listening to on your headphones every few seconds in case anyone calls you over. It’s a long wait but finally - you’re up next. You walk up to the cubicle, place your passport on the desk separating you from the border control officer who looks you up and down, then asks:

“When did you last display symptoms of COVID-19? You never had it? Mhm… okay…. No, sorry, we can’t admit you today.”

Sound like a bad sci-fi dystopian movie? It could be reality sooner than you think. ‘Immunity passports’ are being very seriously considered as a way of monitoring and containing the coronavirus pandemic as countries exit lockdown and try to return to some semblance of ‘normal’. Used as proof of immunity from past infection until we have a working vaccine, these documents started being trialled in Estonia in May. Around the same time, developers of the NHS app said its facial recognition technology could also be used for the UK’s very own COVID-19 ‘immunity passports’. But all’s not as straightforward as it may appear.

A viable certificate?

“Immunity passports create far more problems than they solve at this stage,” says Zulfikar Ramzan, data security and privacy expert, and CTO of RSA. “As they stand today, immunity passports [have] numerous problems. These challenges range from the accuracy of the underlying data and the difficulty of protecting that data, to concerns about its subsequent fair and ethical use. It’s unclear how such a wide range of issues can be effectively addressed.”

Ramzan’s mention of the underlying data’s accuracy is not accidental, and could be used as the main argument against the existence of ‘immunity passports’. In late April, the World Health Organisation (WHO) published a scientific brief in which it warned that there is not enough research to conclude that a person who has had the coronavirus will not contract it again.

“Some governments have suggested that the detection of antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, could serve as the basis for an ‘immunity passport’ or ‘risk-free certificate’ that would enable individuals to travel or to return to work assuming that they are protected against re-infection. There is currently no evidence that people who have recovered from COVID-19 and have antibodies are protected from a second infection,” the WHO stated.

Although the brief was published on 24 April, the WHO’s warning not only failed to steer governments away from considering the idea, but also failed to stop countries such as Estonia from trialling ‘immunity passports’.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Taavet Hinrikus, founder of online money transfer service Transferwise and a member of Back to Work, the non-governmental organisation developing Estonia’s ‘immunity passports’, told Reuters that the tech could prove helpful once the immunity to coronavirus is better understood.

“Digital immunity passport aims to diminish fears and stimulate societies all over the globe to move on with their lives amidst the pandemic,” he said.

However, a Transferwise spokesperson told IT Pro that “it's still quite early days for us to say how the trials are going”.

Data dilemma

Just like the NHS contact-tracing system and app, the ‘immunity passports’ have digital rights campaigners and privacy experts alike worried about how the data will be stored.

Ramzan believes the implementation of immunity passports “will result in a massive data lake of medical information” that, due to its sensitive nature of this data, “will be highly sought after by threat actors”. What’s more, the rapid pace at which the UK government is seeking to reopen the country means that time is not on anyone’s side.

“Anyone attempting to build a data lake for immunity passports will assuredly have a giant target on their back. More so, given the tremendous pressure to put a solution in place swiftly, it is almost certain that the designers and implementers of an immunity passport solution will make significant errors,” he says.

“Another core issue is data governance. In that vein, one must consider who will have access to the data, how mechanisms for controlling access will be enforced, and how to mitigate the risk of this data being abused. An immunity passport system involves the creation of a larger-scale surveillance infrastructure that will collect data beyond the purposes of determining people who are potentially immune to COVID-19. Some people may be willing to contribute their personal data into the system to help address the current pandemic situation. However, they may not wish to have their data used for other purposes.”

Ramzan also warns that immunity passports could lead to widespread discrimination.

“The same data collected for an immunity passport system could be used in making employment decisions or in gleaning people’s lifestyle patterns. Once a large-scale surveillance infrastructure is created and widely deployed, it may be too late to undo its future effects,” he says.

A passport to discrimination?

Jim Killock, executive director of digital rights organisation Open Rights Group, holds a similar opinion, comparing the ‘immunity passport’ to the contact-tracing app, the launch of which has been now delayed to the fourth quarter of the year.

“They might be signed voluntarily but they might, in effect, become quite compulsory. They might also lead to people suffering discrimination or being denied services and certain circumstances,” he warns.

“For instance, an employer might say: ‘I'm only going to put people who've got the immunity certificate into these jobs’, or ‘I'm only going to hire people with immunity certificates’, or give preferential treatment to those with immunity certificates.”

Although ‘immunity passports’ are mostly associated with being carried by employees returning to the workplace post-lockdown, Killock warns that, due to the current lack of guidelines, the certification might be rolled out in other public places such as bars and restaurants.

“Somebody might say: ‘I won't serve people in this bar unless they show me that they've got the [contact-tracing] app or immunity certificates,’ or something like that. If an immunity certificate is to be used for something, then perhaps the purposes for which it’s used need to be pretty tightly defined and the government perhaps should think through why it does want it to be used, rather than creating a free-for-all where it just gets used as people see fit.”

Killock warns that the current lack of legislation has the capability to “easily lead to problems”, adding that the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), which is responsible for promoting good practice in handling personal data as well as providing guidance on data protection, “seems to be very quiet” on the issue of the passports.

Nevertheless, Killock says that ‘immunity passports’ “can be done in a way that's very simple and does not threaten people's privacy”.

“Or it can be attached to somebody's identity, part of a huge database, perhaps combined with other data, and have the possibility of something very intrusive,” he adds.

Ramzan believes that, currently, “there are far too many unknowns when it comes to immunity passports”.

“At the most basic level, we do not even know how to reliably determine whether a person is immune to COVID-19,” he says.

“Even though COVID-19 has accelerated the use of digital throughout the world, we are not always better off using technology to solve every problem related to the pandemic. Just because you can potentially use it to solve a problem does not mean you should.”

Having only graduated from City University in 2019, Sabina has already demonstrated her abilities as a keen writer and effective journalist. Currently a content writer for Drapers, Sabina spent a number of years writing for ITPro, specialising in networking and telecommunications, as well as charting the efforts of technology companies to improve their inclusion and diversity strategies, a topic close to her heart.

Sabina has also held a number of editorial roles at Harper's Bazaar, Cube Collective, and HighClouds.

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Redis unveils new tools for developers working on AI applications

Redis unveils new tools for developers working on AI applicationsNews Redis has announced new tools aimed at making it easier for AI developers to build applications and optimize large language model (LLM) outputs.

By Ross Kelly Published

-

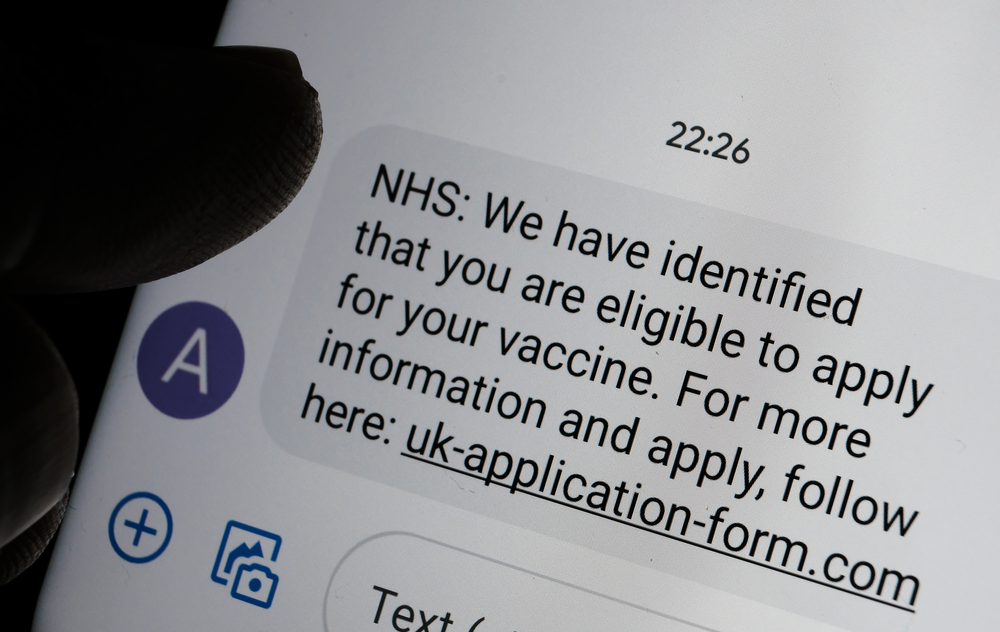

Phishing emails target victims with fake vaccine passport offer

Phishing emails target victims with fake vaccine passport offerNews Scammers could steal victims’ personal information and never deliver the illegal goods, Fortinet warns

By Rene Millman Published

-

COVID-related phishing fuels a 15-fold increase in NCSC takedowns

COVID-related phishing fuels a 15-fold increase in NCSC takedownsNews The NCSC recorded a significant jump in the number of attacks using NHS branding to lure victims

By Bobby Hellard Published

-

COVID vaccine passports will fail unless government wins public trust, ICO warns

COVID vaccine passports will fail unless government wins public trust, ICO warnsNews Data watchdog's chief Elizabeth Denham warns that it’s not good enough to claim ‘this is important, so trust us’

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet Published

-

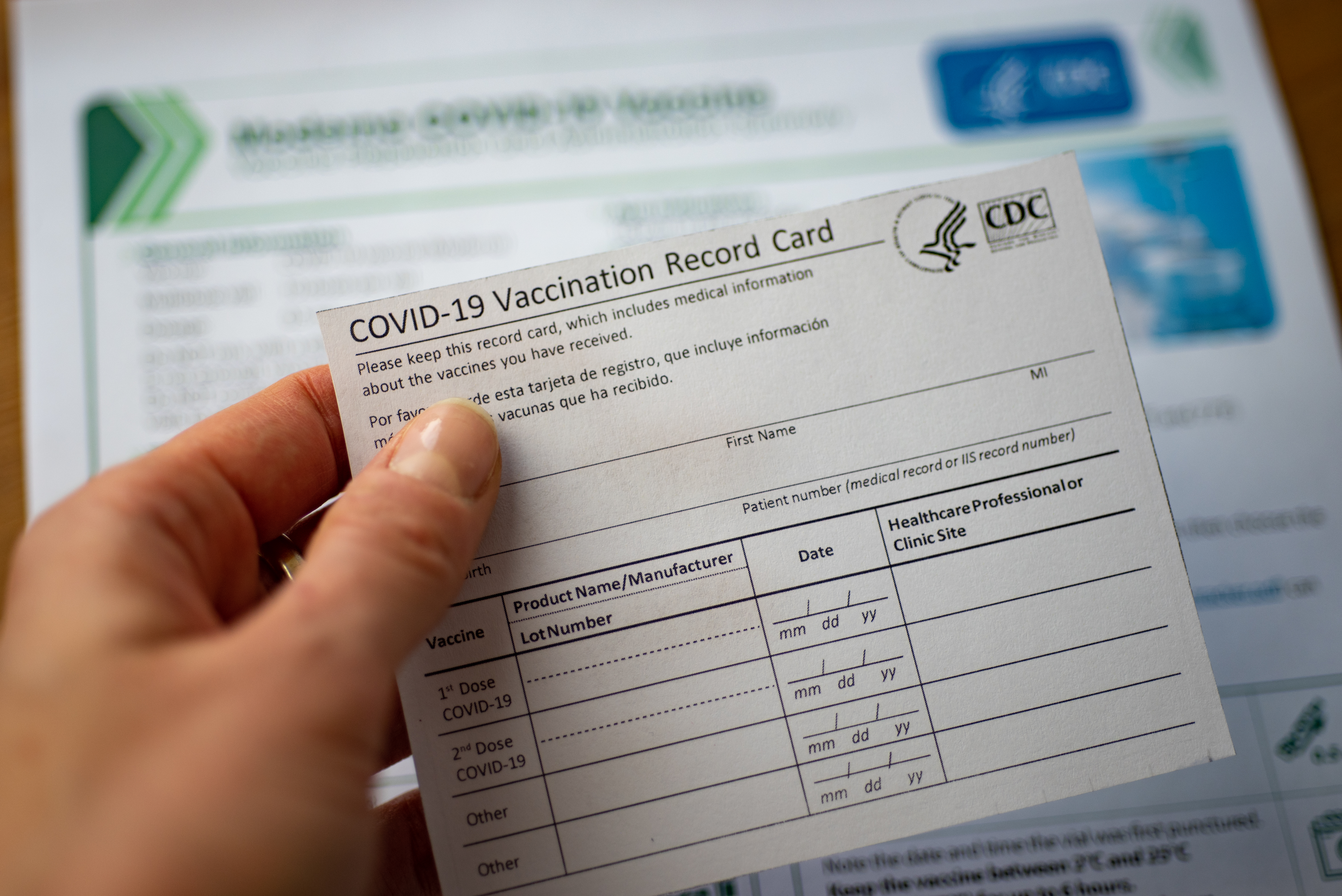

Fake COVID vaccination certificates available on the dark web

Fake COVID vaccination certificates available on the dark webNews Fast-growing market emerges for people wanting quick vaccine proof to travel abroad

By Rene Millman Published

-

Cyber security firm saw attacks rise by 20% during 2020

Cyber security firm saw attacks rise by 20% during 2020News Trend Micro found attackers also heavily targeted VPNs

By Danny Bradbury Published

-

Hackers using COVID vaccine as a lure to spread malware

Hackers using COVID vaccine as a lure to spread malwareNews Cyber criminals are impersonating WHO, DHL, and vaccine manufacturers in phishing campaigns

By Rene Millman Published

-

Website problems slow coronavirus vaccine rollout

Website problems slow coronavirus vaccine rolloutNews Florida is the epicenter of website issues, as patients struggle with malfunctioning sites and hackers

By Danny Bradbury Published

-

NHS COVID-19 app failed to ask users to self-isolate due to 'software glitch'

NHS COVID-19 app failed to ask users to self-isolate due to 'software glitch'News The bug is the latest in a long line of errors and glitches to plague the government's contact-tracing app

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet Published