A deep-dive into AMD's Zen 2 architecture and next-gen EPYC chips

We dig into the next generation of EPYC data centre processors, dubbed 'Rome'

AMD announced its next-generation data centre processor, dubbed Rome, at a special event last week. We've been digging behind the headlines to see both what it means for the data centre and how it might influence AMD's next-generation Zen-based processors.

What do we know?

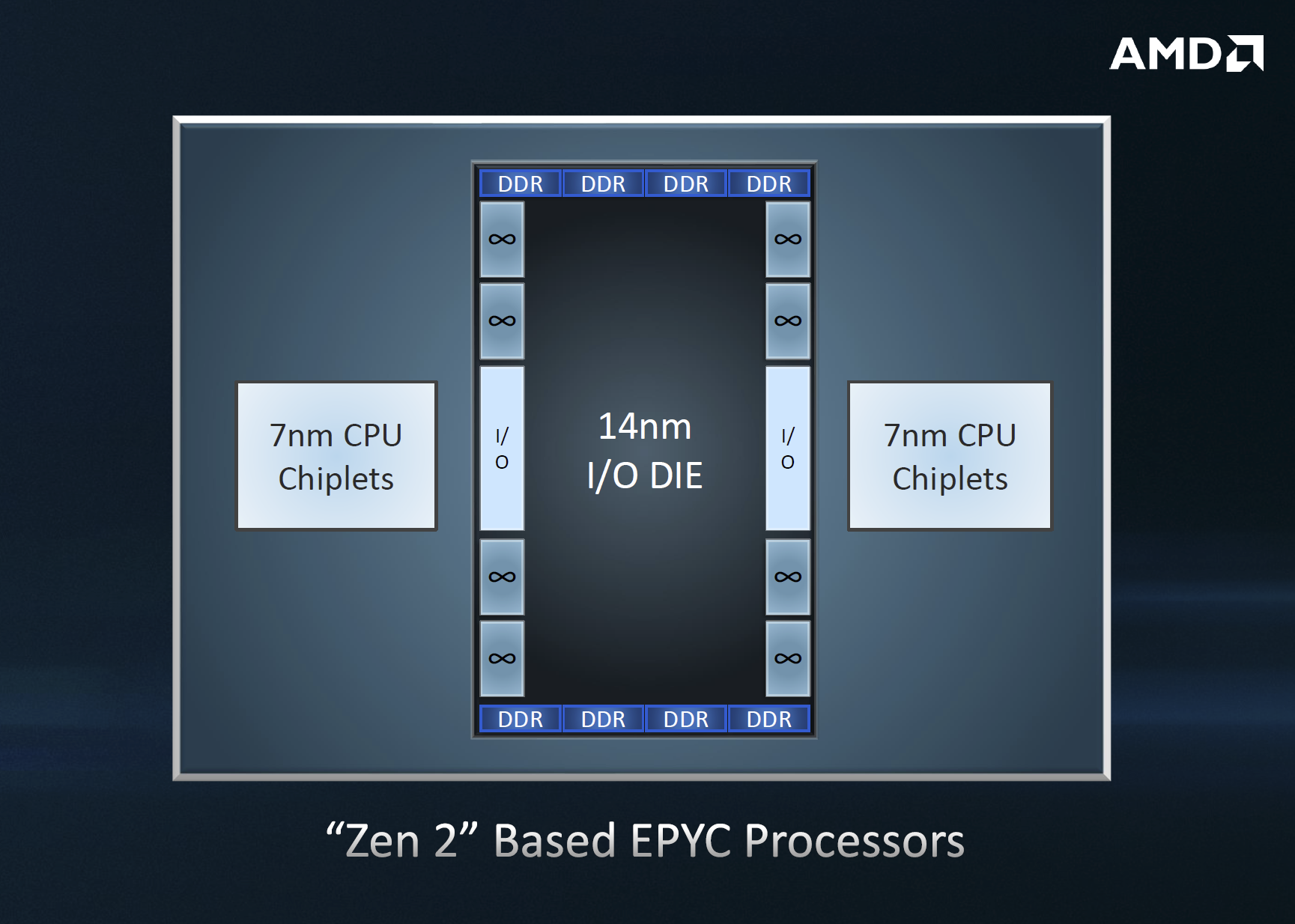

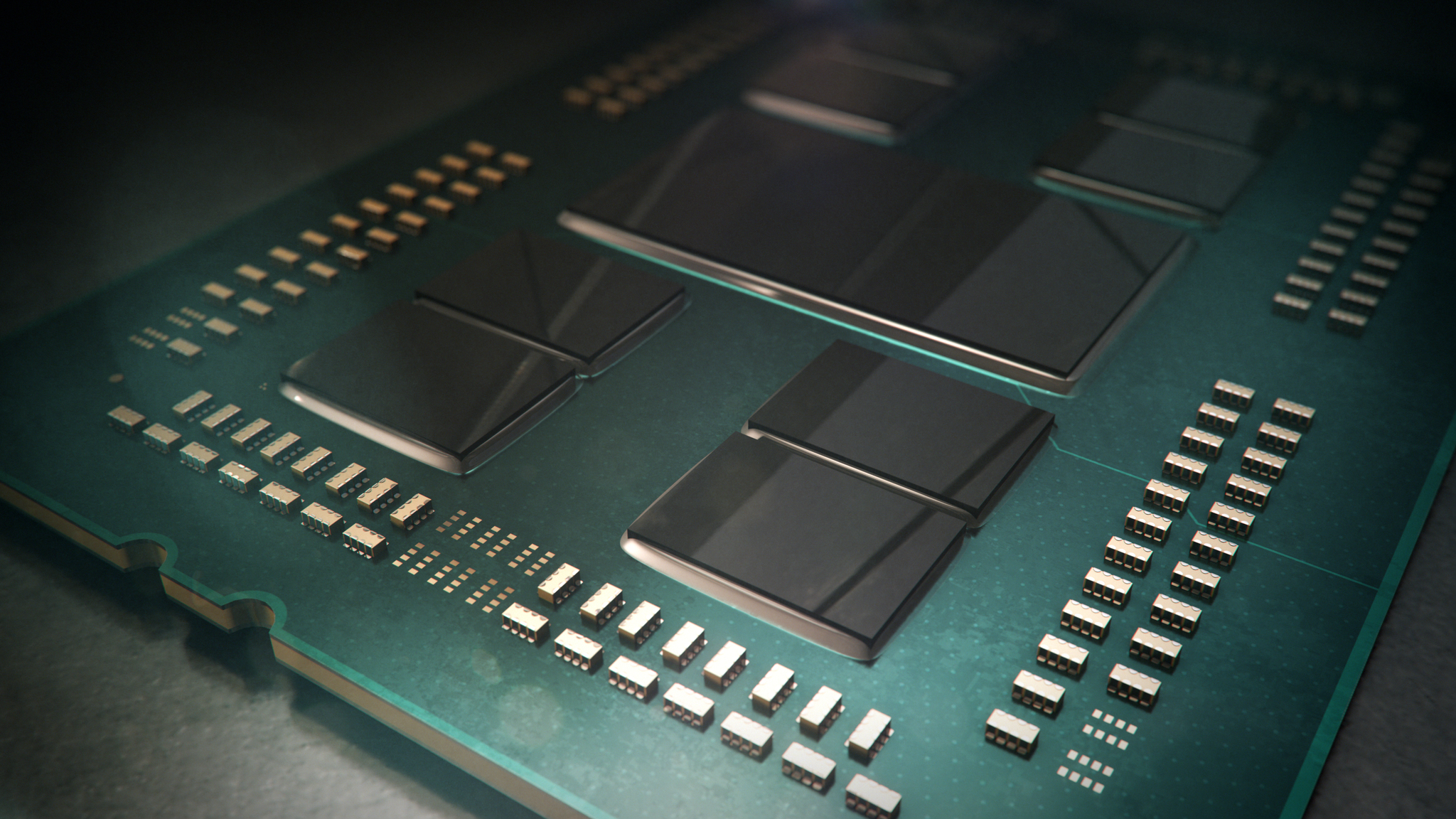

AMD has revealed quite a lot about the new processors. Rome will use AMD's Zen 2 processor architecture, with a maximum number of 64 Zen 2 cores packed onto one board. In total, it will have nine pieces of silicon: eight 7nm "chiplets" and one 14nm I/O die sitting in the middle. Here's a simplified model of how that will look:

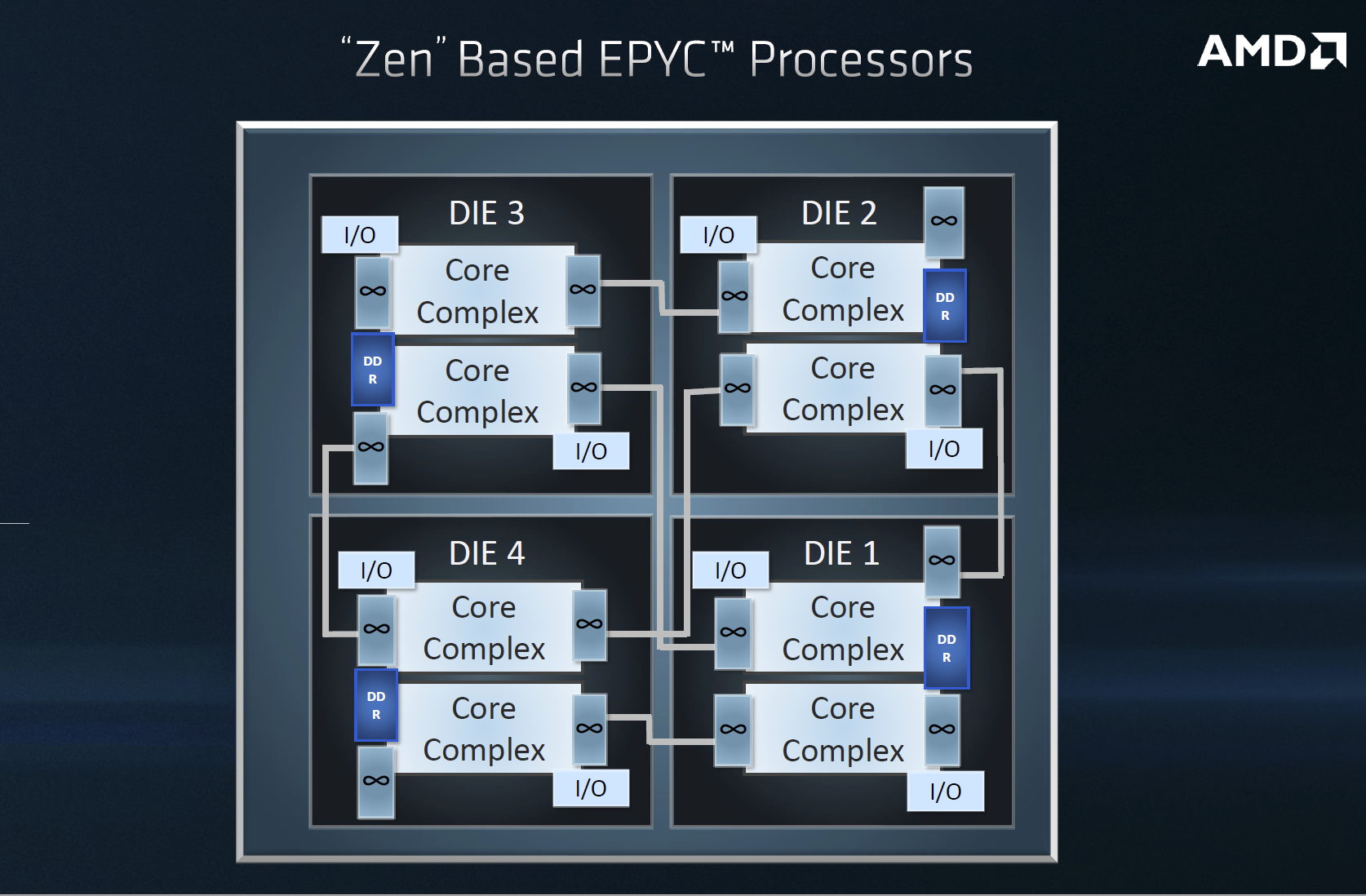

The name "chiplets" is new, but actually AMD performed a similar trick with its first generation of EPYC processors. That time, though, the die that included the Zen core complexes also integrated the I/O and DDR controllers as shown below:

Why has AMD decided to separate out the I/O into a separate die in Rome? Because it believes I/O doesn't "scale" well to 7nm from 14nm - you simply don't get the performance advantages to justify the cost and wastage - and says that with this design that "each IP [is] in its optimal technology".

This makes sense, and perhaps is one reason why Intel is struggling to move from 14nm to 10nm on its own designs.

The change also means that all the chiplets have equal access to the eight DDR memory channels, so you avoid latency generated by the chiplets needing to "hop" over a neighbour to access a module.

AMD doesn't appear to have made major changes to its Infinity Fabric, the key to shuffling data from one core to another (and the outside world), other than to tell us it was "enhanced".

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

What don't we know?

AMD is still holding plenty of information close to its chest. We don't know what frequencies these new processors will run at, with our only clue being that they will use a similar thermal envelope to the current EPYC chips (up to 180W).

It's interesting to speculate what that might mean. Current EPYC processors run with a base clock of between 2GHz and 2.4GHz, with a maximum single-core boost rate of 3.2GHz. While a drop from 14nm to 7nm surely won't double frequencies, we wouldn't be surprised if certain EPYC Zen 2 chips emerged with base rates of 3GHz - but this is pure speculation.

We also don't know pricing or availability, other than "next year". It has already given samples to its key customers, though, so this isn't vapourware.

Zen 2 EPYC speed and performance

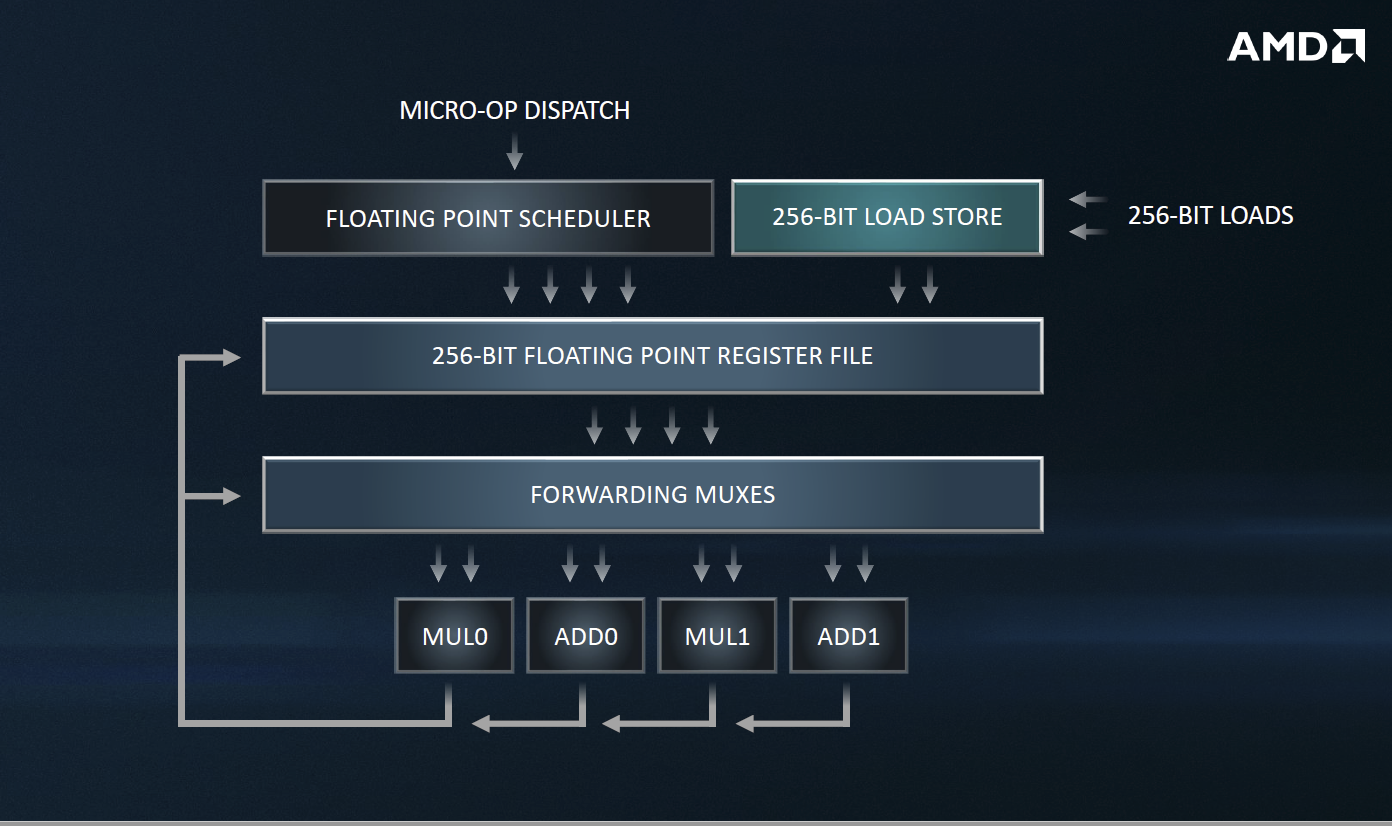

AMD is making some bold claims with regards to its new chips' speed. It has doubled the floating point width to 256-bit, doubled the load/store bandwidth and increased the dispatch/retire bandwidth - all of which translates into much-improved floating point performance. Indeed, AMD promises a 400% improvement.

In addition, it claims that it has improved the branch predictor, has better instruction pre-fetching and has "re-optimized" the instruction cache. Together with a larger operation cache, this should again mean a boost in speed and less latency.

AMD is also keen to talk about throughput. Here, it claims that the doubled floating point register file, doubled core density and improved execution pipeline results in double the throughput compared to the current EPYC products.

One slide from the presentation talks of a 25% performance improvement on the same power, but that's a theoretical 25% based on the move to 7nm. The same slide promised twice the density and half the power to deliver the same level of performance as current chips.

Right now, we have no independent benchmarks to verify AMD's speed claims. At AMD's Next Horizon event, though, we did see three systems go head to head in the C-Ray benchmark.

The single-socket 1P Rome-based system finished the test in 27.7 seconds, beating a dual-socket EPYC system by 0.7 seconds. Intel's rival, dual-socket Xeon machine - which used a top-of-the-range chip - finished in 30.5 seconds.

This puts Rome into high-performance computing territory, with Cray announcing that its Shasta supercomputer (being built for the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory) will use Rome-based CPUs.

We should also note that they'll be used in partnership with AMD Radeon Instinct MI60 GPUs. These were also announced at the event and are again based on 7nm technology, with the promise of excellent scalability.

AMD vs Intel

So what advantages does AMD have over Intel, other than the fact it's actually moving on from 14nm/12nm architecture (which is something that Intel is badly struggling to do right now)? Well, AMD does hold some key leads.

First, I/O density. This was already an advantage for EPYC over Xeon Scalable, with support for up to 2TB of DDR4 memory over eight channels. The Xeon can support 768GB per processor, so 1.54TB over a dual-socket machine. With Rome, AMD is doubling down on this advantage: it can now support 4TB of RAM.

Even without all these enhancements, the current generation of EPYC's I/O advantages mean you don't need to buy a two-socket Xeon server if you're looking for memory bandwidth - and that has the added advantage of reducing licensing costs (especially for VMware customers).

Rome also adds support for PCIe 4.0, which will particularly benefit multi-GPU systems. Will it have more PCIe lanes? We don't know yet, but even if AMD sticks with 128 it holds the numerical advantage over Intel: Xeons support 48 lanes of PCIe per CPU, plus 20 lanes in the chipset. So in a one-socket config, it has 68 lanes; on a two-socket config, it's 116.

Intel does have its own advantages. One is due to Intel's legacy as a server provider: if you want to migrate an Intel-based physical server to a virtual host, you can't use AMD hardware.

Another is, historically at least, that Xeon chips are faster in general use and in database applications. Some of that performance lead was due to the speed of the interconnects, and AMD's architectural changes in Rome appear to have solved that to some extent. We shall see.

EPYC motherboard compatibility

Will you need to replace your existing EPYC motherboards in order to take advantage of these shiny new chips? Allegedly, no. AMD is promising that all existing motherboards will be compatible with Rome chips, although you'll probably need to flash the ROM.

Future mobile and desktop processors

The main thing this news means for the future of mobile and desktop chips is that the next generation of Ryzen processors will use a similar structure: a 7nm die for the chiplets plus a 14nm die for I/O. The whole point of AMD's approach is that it's scalable, from Ryzen mobile processors all the way up to the EPYC chips for data centres.

The shift to 7nm for laptops could be particularly interesting. Intel has had the lead for laptop power efficiency for years, so if AMD can indeed offer the same power efficiency benefits (such as the same performance for half the power consumption) then 2019 and 2020 could see some genuine competition in that market.

We can't see AMD shaking Intel's tree for desktop chips, however. Intel still has a clear lead for per-clock desktop performance here, and the bigger jump appears to be in power efficiency rather than outright performance. However, AMD has surprised us by the strength of its EPYC processors. Perhaps it will surprise us on the desktop as well.

Tim Danton is editor-in-chief of PC Pro, the UK's biggest selling IT monthly magazine. He specialises in reviews of laptops, desktop PCs and monitors, and is also author of a book called The Computers That Made Britain.

You can contact Tim directly at editor@pcpro.co.uk.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Supercomputing in the real world

Supercomputing in the real worldSupported Content From identifying diseases more accurately to simulating climate change and nuclear arsenals, supercomputers are pushing the boundaries of what we thought possible

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Discover the six superpowers of Dell PowerEdge servers

Discover the six superpowers of Dell PowerEdge serverswhitepaper Transforming your data center into a generator for hero-sized innovations and ideas.

By ITPro Published

-

Inside Lumi, one of the world’s greenest supercomputers

Inside Lumi, one of the world’s greenest supercomputersLong read Located less than 200 miles from the Arctic Circle, Europe’s fastest supercomputer gives a glimpse of how we can balance high-intensity workloads and AI with sustainability

By Jane McCallion Published

-

AMD eyes networking efficiency gains in bid to streamline AI data center operations

AMD eyes networking efficiency gains in bid to streamline AI data center operationsNews The chip maker will match surging AI workload demands with sweeping bandwidth and infrastructure improvements

By Ross Kelly Published

-

Enhance end-to-end data security with Microsoft SQL Server, Dell™ PowerEdge™ Servers and Windows Server 2022

Enhance end-to-end data security with Microsoft SQL Server, Dell™ PowerEdge™ Servers and Windows Server 2022whitepaper How High Performance Computing (HPC) is making great ideas greater, bringing out their boundless potential, and driving innovation forward

By ITPro Last updated

-

Dell PowerEdge Servers: Bringing AI to your data

Dell PowerEdge Servers: Bringing AI to your datawhitepaper How High Performance Computing (HPC) is making great ideas greater, bringing out their boundless potential, and driving innovation forward

By ITPro Last updated

-

Dell Technologies AI Fabric with Dell PowerSwitch, Dell PowerEdge XE9680 and Broadcom stack

Dell Technologies AI Fabric with Dell PowerSwitch, Dell PowerEdge XE9680 and Broadcom stackwhitepaper How High Performance Computing (HPC) is making great ideas greater, bringing out their boundless potential, and driving innovation forward

By ITPro Published

-

Drive powerful AI insights with an open ecosystem

Drive powerful AI insights with an open ecosystemwhitepaper Dell PowerEdge XE9680 server with AMD Instinct™ MI300X Accelerator and ROCm™ 6 open software platform

By ITPro Last updated