Presidential campaign apps serve as data collection tools

Campaign apps give access to users’ contacts, approximate location, Bluetooth and more

The official app for the Trump campaign is doubling-up as a powerful data collection tool, accessing users' users’ contacts, location and Bluetooth connection.

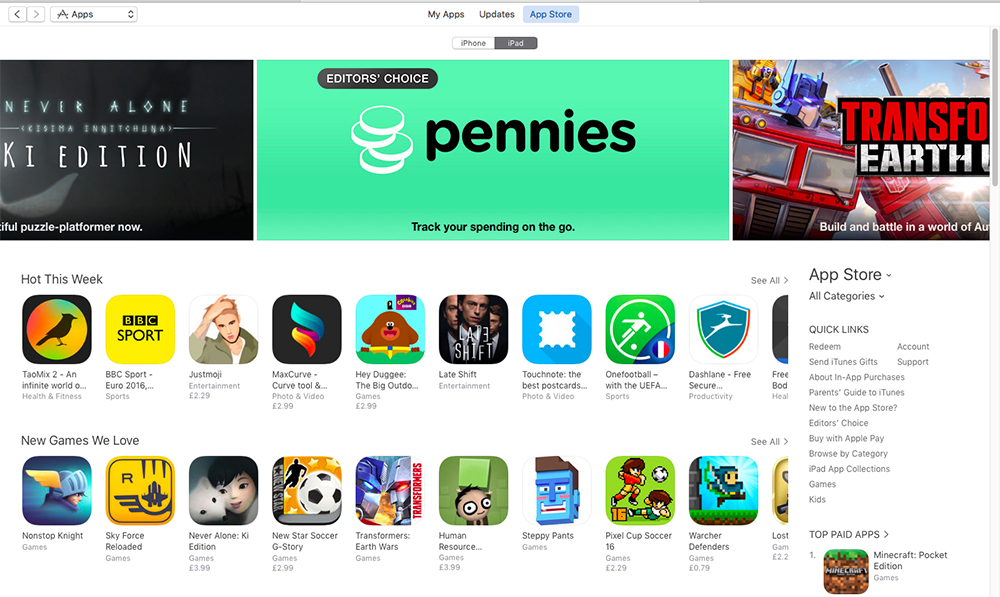

Data collection and targeted online messaging are integral to election cycles. While the 2016 election saw the use of social media platforms to reach voters, the 2020 election cycle has turned to campaign apps promoted by the candidates.

These apps, distributed via the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store, enable the Trump and Biden campaigns to directly to voters and collect huge amounts of user data without relying on social media platforms or exposing themselves to fact-checking.

The Trump campaign launched its official app in April. Since debuting, users have downloaded the app 780,000 times, according to the measurement service Apptopia. While the app features carefully curated feeds meant to reinforce the Trump campaign’s main talking points, it also serves as a powerful data-collection tool.

When signing up for the app, users must provide their full name, phone number, email address and zip code, and they are also encouraged to share the campaign app with their existing contacts. The campaign aims to reach likely Trump voters and collect each of these voters’ mobile numbers.

The strategy also includes requesting access to location data, phone identity and control over the device’s Bluetooth functions.

The Biden campaign launched its own app, though it asks for less information than the Trump campaign’s app. Beyond basic network and notification permissions, the Team Joe Campaign App requests access to users’ contacts.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

According to MIT Technology Review, the Trump campaign app’s use of Bluetooth is especially notable as Bluetooth beacons were recently found in campaign yard signs. As an individual passes a campaign sign with a beacon embedded in it, they’re recorded and identified using Bluetooth.

The campaign uses this data to build a profile, and then uses that profile to target advertising at specific individuals or people like them.

For politicians, individualized campaign apps blur the line between government and private communication. They also allow campaigns and government officials to largely avoid fact-checking. When using such apps, the line between government and campaign isn’t always clear.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Google toughens enforcement of 30% revenue share with developers

Google toughens enforcement of 30% revenue share with developersNews Reports indicate the updates could come as soon as next week

By Justin Cupler Published

-

Best iPhone apps for 2019

Best iPhone apps for 2019Best Get the most out of the new range of iPhones with the top business, productivity and collaboration apps

By Clare Hopping Published

-

Apple outlines plan to take smaller revenue cut from ‘reliable’ apps

Apple outlines plan to take smaller revenue cut from ‘reliable’ appsNews Apps of any kind will also be eligible to offer subscriptions soon

By Aaron Lee Published

-

Apple appoints Jeff Williams as COO

Apple appoints Jeff Williams as COONews Phil Schiller’s responsibilities expand to include management of App Store across platforms

By Clare Hopping Published

-

Apple App Store: Top 10 reasons why apps are rejected

Apple App Store: Top 10 reasons why apps are rejectedNews Developers get guidance on how the approval process works

By Khidr Suleman Published

-

Five years of app stores, and software has changed forever

Five years of app stores, and software has changed foreverIn-depth Apple's pioneering App Store has changed the way consumers buy software. And businesses are following.

By Stephen Pritchard Published

-

Apple beefs up iCloud security

Apple beefs up iCloud securityNews Two-step verification for Apple ID users on iCloud, App Store and iTunes.

By Rene Millman Published

-

Google Maps app set to return to Apple iOS devices?

Google Maps app set to return to Apple iOS devices?News Report in the Wall Street Journal suggests search giant's navigation app could soon be made available again to iOS users.

By Caroline Donnelly Published