The Boeing 737 MAX debacle shows you can no longer escape liability due to poorly configured code

Known vulnerabilities in Boeing’s flight software led to two fatal crashes, as well as a landmark decision with major ramifications for software development

In case law, there are a few times when a single landmark decision reshapes or reframes the legal landscape. At the tail end of last year, that’s exactly what happened – and anyone involved in software development should take note.

The event was a memorandum decision from the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware, which framed its response to a matter relating to software vulnerability. This decision, which caused Boeing to settle for an eye-watering $237.5 million (approximately £210 million), will change the commercial landscape for good.

Up to this point, there have been numerous instances where vulnerabilities in IT systems have been left unaddressed, yet directors have managed a lucky escape. Times, however, are changing. There are two key learnings for anyone involved with software development. First, shareholders, investors and lawyers are now equipped with a better understanding of exploits and the steps that should be taken to address known significant threats. Second, they’re no longer prepared to stomach losses when directors and management fail to exercise reasonable care, skill and diligence.

This better understanding coupled with investors no longer prepared to weather poor decision-making means the days of escaping legal liability due to poorly configured code, failing to address reasonably foreseeable flaws or overlooking known threats, are gone. Shareholders are awake and class actions will follow. Management's luck has run out.

Revisiting a lucky escape for Sony

In November 2014, Sony Pictures Entertainment (SPE) fell foul of a destructive cyber attack launched by a nation-state actor. Shortly after the attack began, SPE ground to a standstill. Half of its personnel couldn’t access their PCs, while half of its servers had been wiped.

Sensitive information relating to contracts was soon released into the wild and unflattering comments contained in emails found their way into headlines. Five films that were set to be released were uploaded to the internet. The business disruption, coupled with the financial losses and the reputational damage, were difficult to assess but likely astronomical.

The prevailing theory is that North Korea used a phishing email to gain entry, although some suggest it would have been as easy to have someone to launch the attack in-person. The physical security, according to experts brought in to assist, was woefully inadequate. Once they’d gained access, poor security and the absence of basic cyber security hygiene allowed the bad actors to run amok in Sony’s systems.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

RELATED RESOURCE

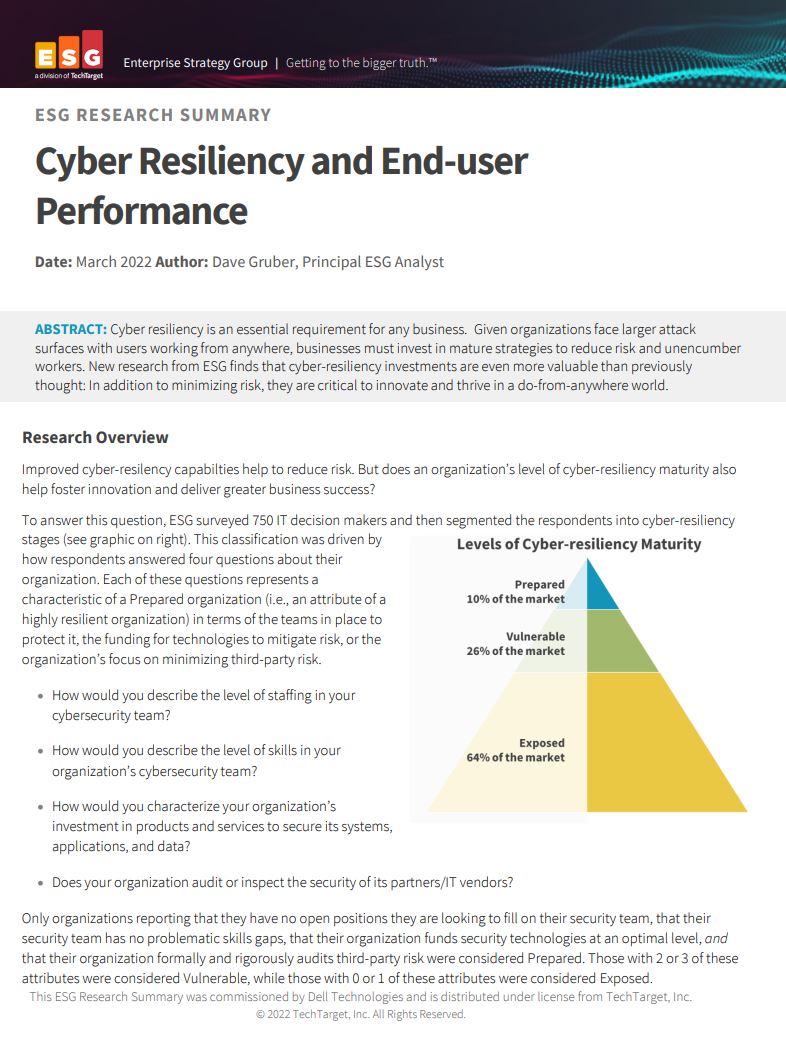

Cyber resiliency and end-user performance

Reduce risk and deliver greater business success with cyber-resilience capabilities

It wasn’t all bad luck, though, as its corporate structure meant investors were a degree of separation away from the targeted entity. SPE is part of Sony Group and it is Sony Group that is listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Whether investors would have been more active if they had felt losses directly is difficult to say. SPE also benefited from the timing. In 2014, investors were easier to hoodwink. Attributing the attack to a nation state gave the whole sorry debacle an air of inevitability.

What could you possibly do? Well for one, you could do the minimum, and start by taking reasonable care, such as implementing a physical security policy and making sure you address threats like phishing, right? This is where the rubber meets the runway.

Boeing shareholder class action

The facts surrounding this matter are desperately sad. For the purposes of corporate law and shareholder class action, nearly 400 people were killed in two separate incidents. Although that fact doesn’t form part of the submission or reasoning, it seems callous to overlook the human cost of this corporate error. The opinion itself runs to over 100 pages. This is intended as a snapshot of what happened, why the claimant shareholders succeeded in their claim and, finally, what directors should do to avoid liability.

So, what happened? Boeing’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was designed as a workaround to solve an engineering problem. The engineering problem had been baked in when Boeing, in its haste to try to keep pace with a competitor, rushed the technical drawing phase. Boeing’s new plane, the 737 Max would have a larger engine. But that shifted the plane’s centre of gravity, causing the plane to send its nose skywards.

Rather than return to the drawing board, MCAS was born. This software would lift the tail and push its nose down. The software was triggered by a single sensor. Boeing knew that this sensor was highly vulnerable to false readings. That sensor was a single point of failure, and it was known to not work properly. On both occasions, minutes after take-off, after experiencing difficulty, the pilots searched the handbook, followed best practice but could not regain control of the plane. Nobody had explained this problem to pilots or regulators.

As a result of these air disasters, Boeing suffered significant disruption. The entire 737 Max fleet was grounded, which resulted in financial losses, a $200 million (roughly £178 million) fine and reputational harm. The court, in reaching its decision, reasoned the directors demonstrated a complete failure by neglecting to establish a reporting system or addressing known significant problems.

The consequences, in turn, can adversely affect a company firm and its share value, which fast-tracks its way to shareholder class actions. With respect to bad coding, unaddressed software vulnerabilities or cyber security threats, this is the matter that lawyers will look to.

What can we learn from the Boeing debacle?

Protecting your business from myriad threats may seem daunting but there are good general rules to follow. To reference a report from the 1989 Marchioness Disaster, risk assessments try to assess relevant risks so appropriate steps can be taken to eliminate or minimise them. Whether it’s a widget, policy, protocols, or even code, it’s elementary risk management to address any and all known threats.

What sources might IT directors, engineers or consultants rely on to provide to assist them in avoiding liability? Building in defensibility is about taking reasonable care. That means any information revealed by a reasonable search ought to be addressed – or there must be extensive contemporaneous notes justifying the decision not to implement, with details provided by the decision maker(s).

For example, IT directors and consultants would do well to implement a well-regarded framework, such as that provided by the National Institute of Standards in Technology (NIST). Moreover, each sector should ensure they read reports directed at their sector. For example, Interpol wrote a report for healthcare agencies across Europe warning about ransomware 12 months before the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) was targeted in the Conti attack. Similarly, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) published a report into threats targeting the legal sector.

Ultimately, it’s not the unknown or unknowable events that could represent an existential threat to your business, but what you do know – but don’t act on – that could be the most painful. This decision will usher in a new sense of urgency for businesses to adopt global industry standards as a minimum, to address the reasonably foreseeable exploits. From now on, you must avoid the avoidable or face the consequences.

Rois Ni Thuama PhD is a doctor of law and an expert in cyber governance and risk mitigation. She is head of cyber governance for Red Sift.

-

Two Fortinet vulnerabilities are being exploited in the wild – patch now

Two Fortinet vulnerabilities are being exploited in the wild – patch nowNews Arctic Wolf and Rapid7 said security teams should act immediately to mitigate the Fortinet vulnerabilities

-

Everything you need to know about Google and Apple’s emergency zero-day patches

Everything you need to know about Google and Apple’s emergency zero-day patchesNews A serious zero-day bug was spotted in Chrome systems that impacts Apple users too, forcing both companies to issue emergency patches

-

Security experts claim the CVE Program isn’t up to scratch anymore — inaccurate scores and lengthy delays mean the system needs updated

Security experts claim the CVE Program isn’t up to scratch anymore — inaccurate scores and lengthy delays mean the system needs updatedNews CVE data is vital in combating emerging threats, yet inaccurate ratings and lengthy wait times are placing enterprises at risk

-

IBM AIX users urged to patch immediately as researchers sound alarm on critical flaws

IBM AIX users urged to patch immediately as researchers sound alarm on critical flawsNews Network administrators should patch the four IBM AIX flaws as soon as possible

-

Critical Dell Storage Manager flaws could let hackers access sensitive data – patch now

Critical Dell Storage Manager flaws could let hackers access sensitive data – patch nowNews A trio of flaws in Dell Storage Manager has prompted a customer alert

-

Flaw in Lenovo’s customer service AI chatbot could let hackers run malicious code, breach networks

Flaw in Lenovo’s customer service AI chatbot could let hackers run malicious code, breach networksNews Hackers abusing the Lenovo flaw could inject malicious code with just a single prompt

-

Industry welcomes the NCSC’s new Vulnerability Research Initiative – but does it go far enough?

Industry welcomes the NCSC’s new Vulnerability Research Initiative – but does it go far enough?News The cybersecurity agency will work with external researchers to uncover potential security holes in hardware and software

-

Hackers are targeting Ivanti VPN users again – here’s what you need to know

Hackers are targeting Ivanti VPN users again – here’s what you need to knowNews Ivanti has re-patched a security flaw in its Connect Secure VPN appliances that's been exploited by a China-linked espionage group since at least the middle of March.