Switch from Zoom: How to run your own videoconferencing platform

Online meetings are here to stay, but the easiest solution isn’t necessarily the best

For most businesses, the pandemic has been a huge disruption – but some have benefited. Delivery services, online supermarkets and streaming sites have all boomed. Perhaps none has seen such a meteoric rise as Zoom.

Zoom’s growth isn’t simply a case of offering the right service at the right time. There were plenty of online meeting platforms to choose from, including 8x8, Cisco Webex and Microsoft Teams, but Zoom was the one that broke out of the business realm to facilitate remote pub quizzes, online fitness classes and virtual family get-togethers.

RELATED RESOURCE

Three tips for leading hybrid teams effectively

A guide to employee motivation and engagement for business leaders

A key reason is ease of use. Zoom made it supremely easy to invite non-subscribers into your meetings, and for those people to join. In the first half of 2020, as its name became synonymous with videoconferencing, it became an obvious default option for businesses seeking a reliable, familiar way for employees to communicate during lockdown.

Now, although pandemic restrictions are finally easing, many organisations intend to allow employees to keep working from home, at least part of the time. And for businesses that settled on Zoom – or some other service – at the start of the pandemic, that raises an important question. Is the service still the right solution for an era where video calls are not a stopgap solution but an integral, ongoing part of your working practices?

As Stefan Walther, CEO of communications solution provider 3CX points out, the downsides of Zoom are starting to become apparent. “A lot of people don’t need the extent of the feature set,” Walther told PC Pro. “It’s a great platform; it works very well, but it comes with a hefty price tag, per-user licences with a lot of add-ons, and a quite expensive dial-in feature.”

It’s time to explore your alternatives – and one you might not have considered is hosting your own videoconferencing service.

Free and easy

You don’t necessarily need to pay for fully functional conferencing software. Jitsi is a complete free-to-use open-source option that includes end-to-end encryption and integration with Google, Microsoft products and Slack. First appearing under the name SIP communicator in the early 2000s, it’s now run by communications specialist 8x8, which supports the ongoing development of Jitsi alongside its commercial hosted videoconferencing solution.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

To get started with Jitsi, you just need something to run the back-end on. Server code for Debian/Ubuntu and Docker can be downloaded for free, along with a range of support packages on GitHub, plus Chrome extensions, iOS and Android apps. Jitsi rooms can be embedded in your own website, and there’s a hosted web front-end at meet.jit.si for anyone who doesn’t want to host it themselves.

If you’re wondering whether Jitsi is good enough for your company, be reassured that some big names rely on it – including Wikimedia, which hosts its own public portal. In choosing a video platform, the organisation said it found that, for meetings of 10-15 participants, Jitsi’s performance was “subjectively on par with Google Meet and Zoom”.

Indeed, the developer says the platform is suitable for hosting unlimited free meetings with up to 100 simultaneous participants – although if you need a bigger capacity, or advanced features such as closed captioning, moderation and analytics, it recommends you step up to the paid-for 8x8 Meet service.

While Jitsi can be appealing for certain scenarios, it’s not your only free option. Google Hangouts, Cisco Webex and others allow free meetings for limited numbers of participants or limited times; 3CX only starts charging for its hosted conferencing solution after the first year’s use.

Web conferencing for education

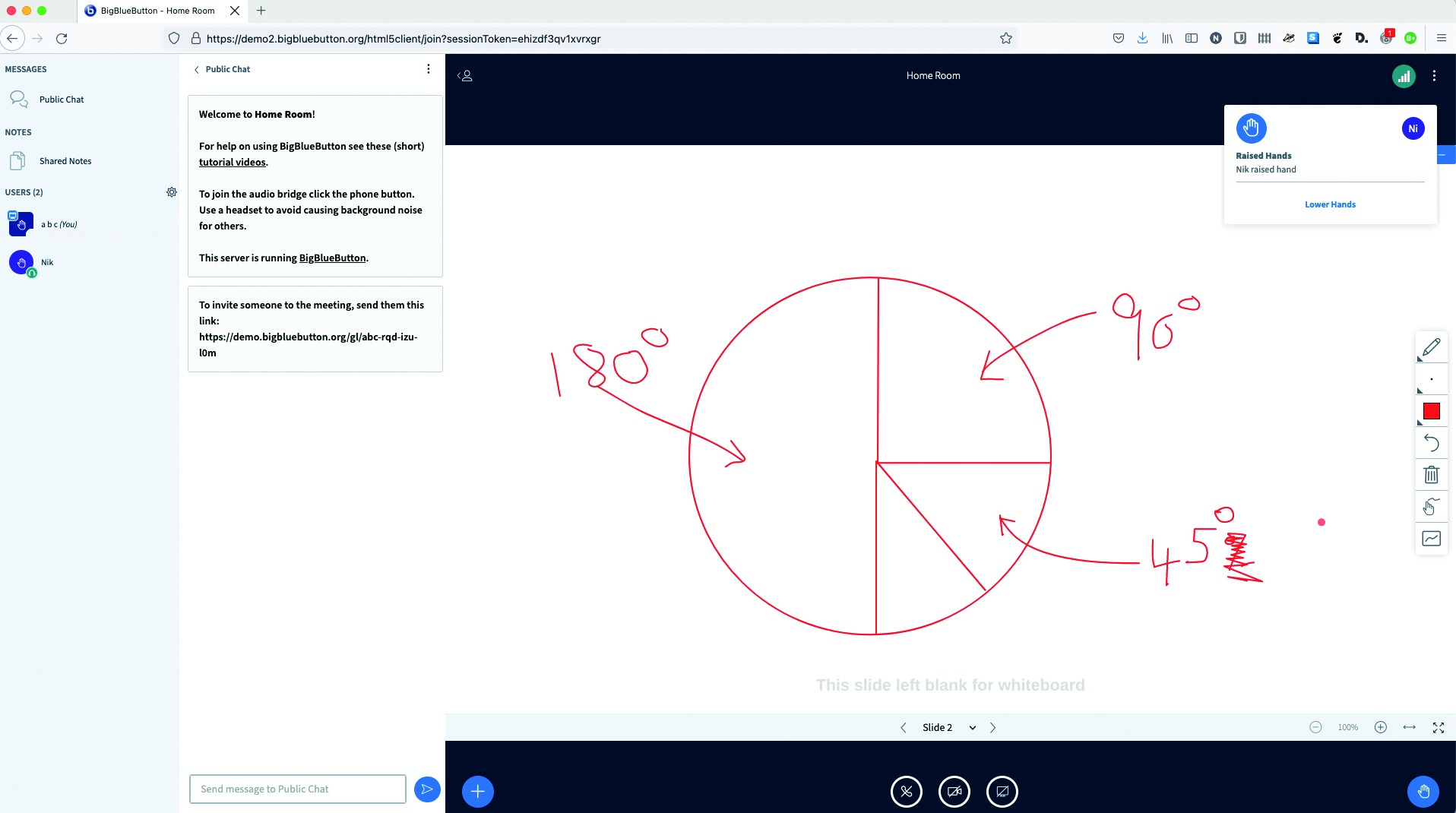

Another free, open-source option is BigBlueButton. It’s a popular choice in education settings: having emerged from the Technology Innovation Management program at Canada’s Carleton University, it’s now supported by more than three quarters of the worldwide market for learning management systems (LMSes).

BigBlueButton is straightforward to deploy. The server runs happily on 64-bit Ubuntu 18.04 inside a Docker container, and it uses no client software at all, relying instead on native browser features. This makes it ideal for home-teaching environments, but also for businesses seeking an easy way to ensure that employees can stay in touch, regardless of what device they’re using or where.

As you’d expect, some of BigBlueButton’s features have a distinctly educational flavour. It supports online whiteboards and allows hosts to pick a random user to answer questions. Like many videoconferencing platforms, it allows the participants to raise a digital hand to ask a question or offer a response, and the host can click to lower all raised hands at once.

However, BigBlueButton sports a range of business staples, such as document sharing and breakout rooms, along with screen sharing and integration with CMS software as well as LMS tools.

Reasons to run your own server

Installing and managing your own videoconferencing solution is more complex than opting for a ready-made alternative, but it has benefits. Businesses and educational establishments can more finely tune their spending and back-end management, as well as gain greater control over add-ons and the location of data.

With third-party services, this type of control varies considerably between the different providers. Zoom account owners and administrators can customise which data centre regions they use for hosting real-time meetings and webinar data, although the default is locked to the region in which your account was originally provisioned.

With 3CX there’s more flexibility. CEO Stefan Walther told us that, on his company’s platform, “you’re always 100% in charge of your location, your data and the people you invite”. There’s no need to install a dedicated app if you’re happy to host meetings in the browser, and British users’ data will stay within the UK while European user data resides within the EU.

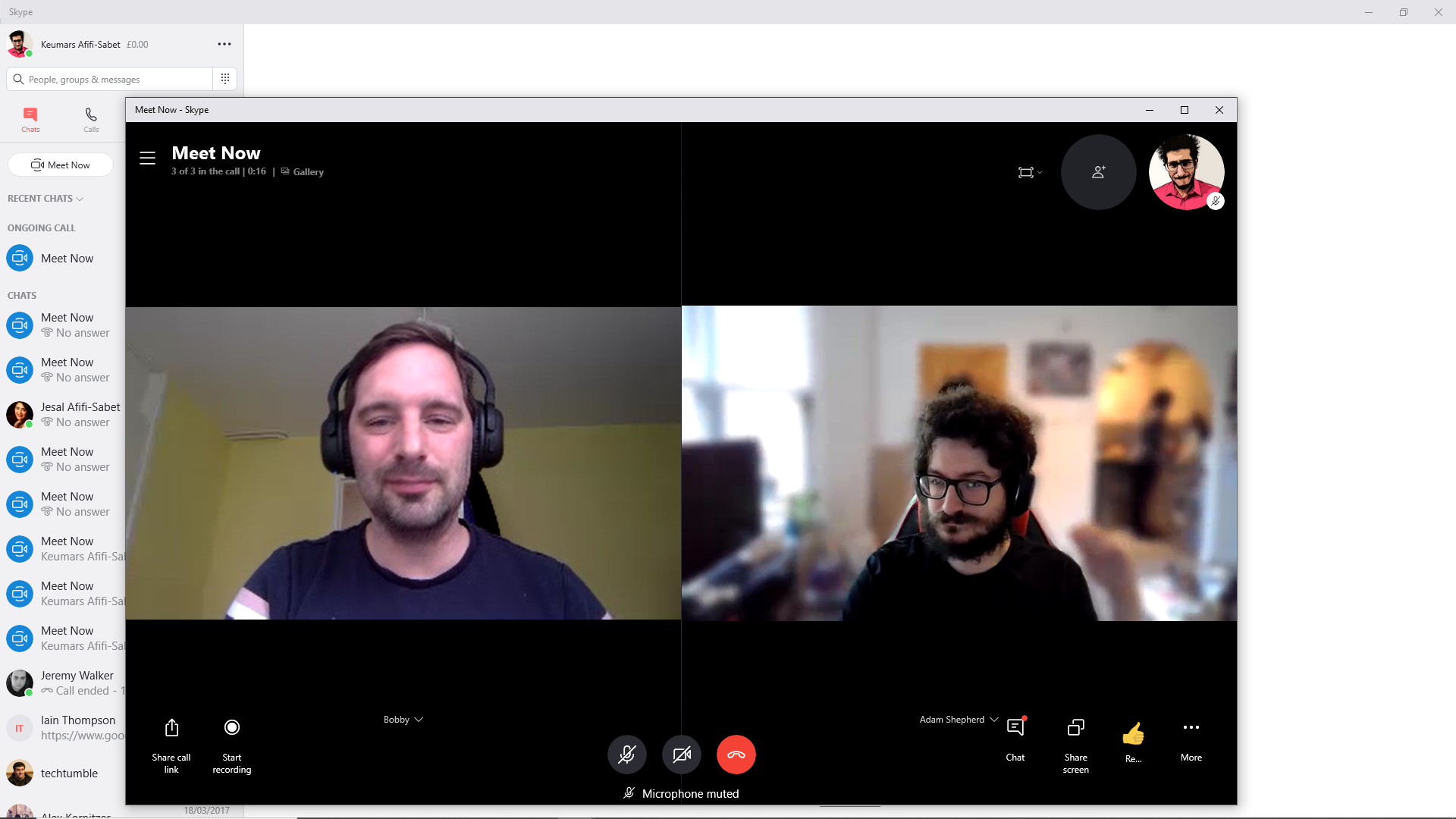

Skype for Business is another service that supports a self-hosted back end; however, owner Microsoft is currently encouraging customers to ditch Skype and move onto Teams instead, which resides wholly on Microsoft’s own servers.

Another factor to consider is the breadth of services you require. Buy into 3CX’s integrated communications service and you’re getting more than just a videoconferencing solution: it’s a fully featured PBX with a lot of extras, including VoIP for regular phone calling, messaging and presence tools, with support for both software clients and physical phones. Skype for Business has a similarly wide-ranging feature set. Having all of this in one place can help productivity, as employees don’t need to mess about switching between multiple tools, but smaller businesses often won’t need to go beyond video, group chat and messaging.

Managing your own service – even if it’s not hosted on your own hardware but cloud services such as Azure or AWS – means that you’re free to switch providers when you choose, or even migrate to an alternative videoconferencing platform entirely. Should you instead choose to roll hosting and app provision into a single payment, you don’t have this flexibility: there might be a minimum lock-in, and even if you migrate because your current provider no longer meets your requirements, there may be residual bills to be paid.

Support and hosting

While features are an important consideration when choosing a conferencing platform, another critical issue is support. A communications server is a key piece of business infrastructure, and you’ll need the expertise to keep it running. In many instances – but by no means all – a charged-for service will often be easier to get up and running more quickly. Likewise, less tech-savvy end users may find it easier to work on the move if they can do so using apps, rather than a mobile browser.

Some services have quick setup wizards for easy deployment, but others expect a significant level of technical know-how on the part of administrators, which may make them an impractical choice for smaller organisations, at least as far as self-hosting is concerned. Even for the larger enterprise, an option that requires constant monitoring could justify adding one to the head count which, over the course of a year, could end up costing just as much as opting for a provider-hosted alternative.

At the same time, depending on which path you choose, you may also have limited recourse to external support. Jitsi, for example, warns that “neither the immediate Jitsi team or 8x8 provide commercial support for Jitsi. Jitsi does enjoy a large developer community with many development shops and individuals that provide support and commercial development services. If you need help, we recommend you do a search or post a request on our Community Forum.” It’s better than nothing, but you might have trouble convincing the board that this is a viable solution.

You’ll need suitable server hardware too. Thankfully, this isn’t a big ask: most services don’t need a ton of resources and will run in a container or virtual machine. Alternatively, you can use a very lightweight dedicated system; Jitsi and 3CX can both be installed on Raspberry Pi devices, for a terrifically cheap one-box solution.

TrueConf is another commercial service that supports the Raspberry Pi – and even allows you to download a ready-made Linux-based image that’s preinstalled with the conferencing software and all necessary documentation.

Redundancy

Running an on-site videoconferencing solution can cut ongoing costs, but it risks creating a single point of failure if your local infrastructure goes down. For this reason, even if you’re happy to own and manage your own communications services, it can make sense to let someone else host the server: cloud-based services should have contingencies for outages and multiple lines with automatic failover.

Many of the solutions discussed here can be hosted on the Azure, AWS or Google Cloud platforms. Amazon’s own Chime communications service, which runs on AWS, goes one step further, offering an SDK that developers can use to integrate its features into their own web or mobile applications, including SIP trunking, chat, collaboration and screen sharing.

Zoom out?

If you’ve only ever thought of videoconferencing as a closed, third-party service, the potential of setting up and operating your own services can be liberating – and economical. However, it also means taking on responsibilities – for installation, for maintenance, and possibly for loss of business if your system goes down.

Taking a cloud-hosted approach reduces that risk, but brings ongoing connectivity and capacity costs to consider, even if the software you’re running is itself free. And if you opt for a system without professional support then a misconfiguration or corrupted upgrade could also prove costly in engineer hours and lost productivity.

We’d recommend therefore that you don’t rush to ditch your current conferencing service. Today’s crop of commercial systems are robust, well-supported and easy to use – and often easier to roll out within an organisation than a self-managed solution.

Rather, the point is this: in past years, online videoconferencing might have seemed like a luxury or a gimmick. That’s no longer the case. Videoconferencing is right at the heart of business, and likely to remain there for a long time to come. It’s time to take a fresh look at your needs, and weigh up whether the time is right to take these crucial services into your own hands.

Nik Rawlinson is a journalist with over 20 years of experience writing for and editing some of the UK’s biggest technology magazines. He spent seven years as editor of MacUser magazine and has written for titles as diverse as Good Housekeeping, Men's Fitness, and PC Pro.

Over the years Nik has written numerous reviews and guides for ITPro, particularly on Linux distros, Windows, and other operating systems. His expertise also includes best practices for cloud apps, communications systems, and migrating between software and services.

-

Why are many men in tech blind to the gender divide?

Why are many men in tech blind to the gender divide?In-depth From bias to better recognition, male allies in tech must challenge the status quo to advance gender equality

By Keri Allan

-

BenQ PD3226G monitor review

BenQ PD3226G monitor reviewReviews This 32-inch monitor aims to provide the best of all possible worlds – 4K resolution, 144Hz refresh rate and pro-class color accuracy – and it mostly succeeds

By Sasha Muller

-

Skype review: Retrofitted for the modern age

Skype review: Retrofitted for the modern ageReviews The video conferencing OG boasts a clean in-meeting interface and most of the features you could ask for

By Keumars Afifi-Sabet

-

Skype takes on Zoom with 'Meet Now' video calling feature

Skype takes on Zoom with 'Meet Now' video calling featureNews Users can join meetings without having to sign-up or install the app

By Sabina Weston

-

Xbox Live, Office 365, OneDrive and Outlook.com suffer outage

Xbox Live, Office 365, OneDrive and Outlook.com suffer outageNews Users were left unable to log into services for hours overnight

By Jane McCallion

-

Microsoft shuts down UK Skype office

Microsoft shuts down UK Skype officeNews Redundancies will ensue, especially in the engineering divisions

By Clare Hopping

-

Skype scraps support for older devices

Skype scraps support for older devicesNews Company ends support for Windows Phone and pre Android 4.03-devices

By Clare Hopping

-

Microsoft signs deal to pre-install apps on Android handsets

Microsoft signs deal to pre-install apps on Android handsetsNews New agreement will put Word, Excel, PowerPoint and Skype in front of Android users in Asia and South America

By Aaron Lee

-

Skype Translator rolling out to Windows Desktops

Skype Translator rolling out to Windows DesktopsNews Skype Translator on Windows now available in six voice and 50 written languages

By Khidr Suleman

-

Kim Dotcom unveils encrypted Skype-rival MegaChat

Kim Dotcom unveils encrypted Skype-rival MegaChatNews Kim Dotcom has launched a new encrypted video calling service, MegaChat, to take on Skype

By Caroline Preece