Companies “wary” of Windows 11 migration challenges as Windows 10 EOL draws closer

A recent study shows that only a fraction are running Windows 11, despite a rapidly-approaching end of life deadline

Most businesses are lagging on Windows 11 migrations, with a study from ControlUp showing that over three-quarters (82%) of devices are still not running on the latest operating system (OS).

This is despite the impending Windows 10 end of life (EOL) slated for late 2025. Following this point, organizations can only pay for three years of updates before the OS is fully unsupported.

Fielding data from over 750,000 devices, the results of ControlUp’s study point to an evident anxiety about OS migration among businesses.

“The clock is ticking for enterprises to adopt the more secure and capable Windows 11, yet many organizations are stuck, unsure about their environment’s readiness,” said Simon Townsend, field CTO at ControlUp.

Organizations are being forced to re-evaluate their endpoint devices, added IDC research director Shannon Kalvar, and it has become “imperative” that businesses plan their move to next generation of operating systems.

Older devices may not be equipped to run Windows 11, which requires a 64-bit CPU, ‘Secure Boot’ capabilities, and a Trusted Platform Module (TPM) 2.0 chip to run.

Of the 82% of devices not yet upgraded, 88% of them are fully equipped for the upgrade. By comparison, just 11% need to be fully replaced to meet the demands of Windows 11 while 1% can be upgraded to meet the requirements before migration.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

With the overwhelming majority of surveyed devices “ready for migration”, there are evidently other considerations for businesses when looking at Windows 11 migrations.

Firms don’t want to repeat difficult migrations with Windows 11

Many businesses are “wary” of the Windows 11 upgrade because of the challenges they faced upgrading to Windows 10, according to Cloudhouse director Mark Gilliand. Cloudhouse is an enterprise Windows user and currently runs on Windows 11.

“The transition to Windows 10 was often lengthy and disruptive, particularly due to issues with legacy applications and compatibility,” Gilliand told ITPro.

“Companies are wary of repeating this experience, with concerns over the cost, time, and potential operational impact of another upgrade,” he added.

RELATED WHITEPAPER

One of the major obstacles, added Gilliand, is ensuring that commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) and “home-grown” business applications will run on the new OS, which he noted is an “often-overlooked challenge” for businesses.

“Even if most vendors have certification for Windows 11, it may only be for the latest release. In-house applications will need testing and tweaking, triggering another round of quality assurance (QA),” Gilliand said.

The “serious challenge” comes when applications have no forward compatibility, he added, stranding business-critical operations on obsolete platforms and raising concerns around compliance.

Microsoft is pushing back against reluctant businesses

To incentivize end-user migration to Windows 11, Microsoft has tried to both persuade and coerce enterprises and businesses into making the switch.

The firm tried to drive the change through the promise of an AI-enhanced Windows 11, with updated features for Copilot Preview for Windows 11 and new plugins for applications like Shopify and Klarna.

Following that move, Microsoft opted for a slightly more aggressive approach by ramping up the price of Extended Security Updates (ESU) for users who have not switched past the October 2025 deadline.

Once the deadline has passed, businesses will have to pay $61 for the first year of updates, followed by $122 for the second year and $244 for the third. This is a significant markup from the Windows 7 ESU program.

Extended updates for this OS only cost users $25 per device for the first year, followed by $50 for the second, and $100 for the third.

George Fitzmaurice is a former Staff Writer at ITPro and ChannelPro, with a particular interest in AI regulation, data legislation, and market development. After graduating from the University of Oxford with a degree in English Language and Literature, he undertook an internship at the New Statesman before starting at ITPro. Outside of the office, George is both an aspiring musician and an avid reader.

-

Geekom Mini IT13 Review

Geekom Mini IT13 ReviewReviews It may only be a mild update for the Mini IT13, but a more potent CPU has made a good mini PC just that little bit better

By Alun Taylor

-

Why AI researchers are turning to nature for inspiration

Why AI researchers are turning to nature for inspirationIn-depth From ant colonies to neural networks, researchers are looking to nature to build more efficient, adaptable, and resilient systems

By David Howell

-

Intune flaw pushed Windows 11 upgrades on blocked devices

Intune flaw pushed Windows 11 upgrades on blocked devicesNews Microsoft is working on a solution after Intune upgraded devices contrary to policies

By Nicole Kobie

-

Dragging your feet on Windows 11 migration? Rising infostealer threats might change that

Dragging your feet on Windows 11 migration? Rising infostealer threats might change thatNews With the clock ticking down to the Windows 10 end of life deadline in October, organizations are dragging their feet on Windows 11 migration – and leaving their devices vulnerable as a result.

By Emma Woollacott

-

Recall arrives for Intel and AMD devices after months of controversy

Recall arrives for Intel and AMD devices after months of controversyNews Microsoft's Recall feature is now available in preview for customers using AMD and Intel devices.

By Nicole Kobie

-

With one year to go until Windows 10 end of life, here’s what businesses should do to prepare

With one year to go until Windows 10 end of life, here’s what businesses should do to prepareNews IT teams need to migrate soon or risk a plethora of security and sustainability issues

By George Fitzmaurice

-

Microsoft is doubling down on Widows Recall, adding new security and privacy features – will this help woo hesitant enterprise users?

Microsoft is doubling down on Widows Recall, adding new security and privacy features – will this help woo hesitant enterprise users?News The controversial AI-powered snapshotting tool can be uninstalled, Microsoft says

By Nicole Kobie

-

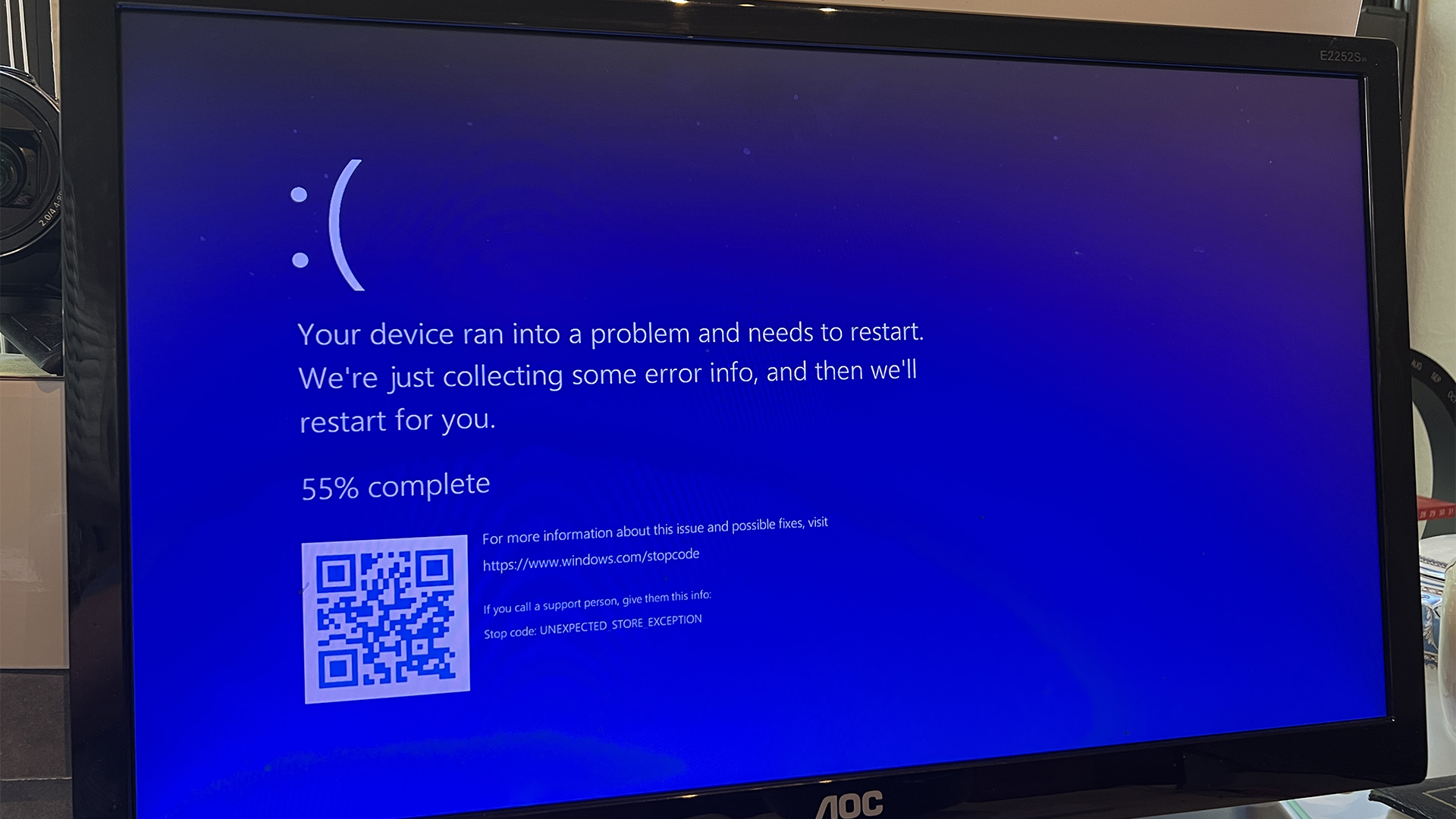

Microsoft pulls Windows update after botched patch causes blue screens, reboot loops

Microsoft pulls Windows update after botched patch causes blue screens, reboot loopsNews Microsoft has pulled a Windows 11 update ahead of next week's Patch Tuesday after encountering a raft of issues

By Nicole Kobie

-

Microsoft patches rollback flaw in Windows 10

Microsoft patches rollback flaw in Windows 10News Patch Tuesday includes protection for a Windows 10 "downgrade" style attack after first being spotted in August

By Nicole Kobie

-

It looks like we’re stuck with Windows Recall: Microsoft confirms option to uninstall was just a ‘bug’

It looks like we’re stuck with Windows Recall: Microsoft confirms option to uninstall was just a ‘bug’News The controversial feature can be disabled, but Microsoft isn't saying much else

By Nicole Kobie