How to pick the perfect SSD for your needs and budget

Not all SSDs are created equal. If you’re choosing which drive to buy, there are several key points to consider

How many gigabytes do you need?

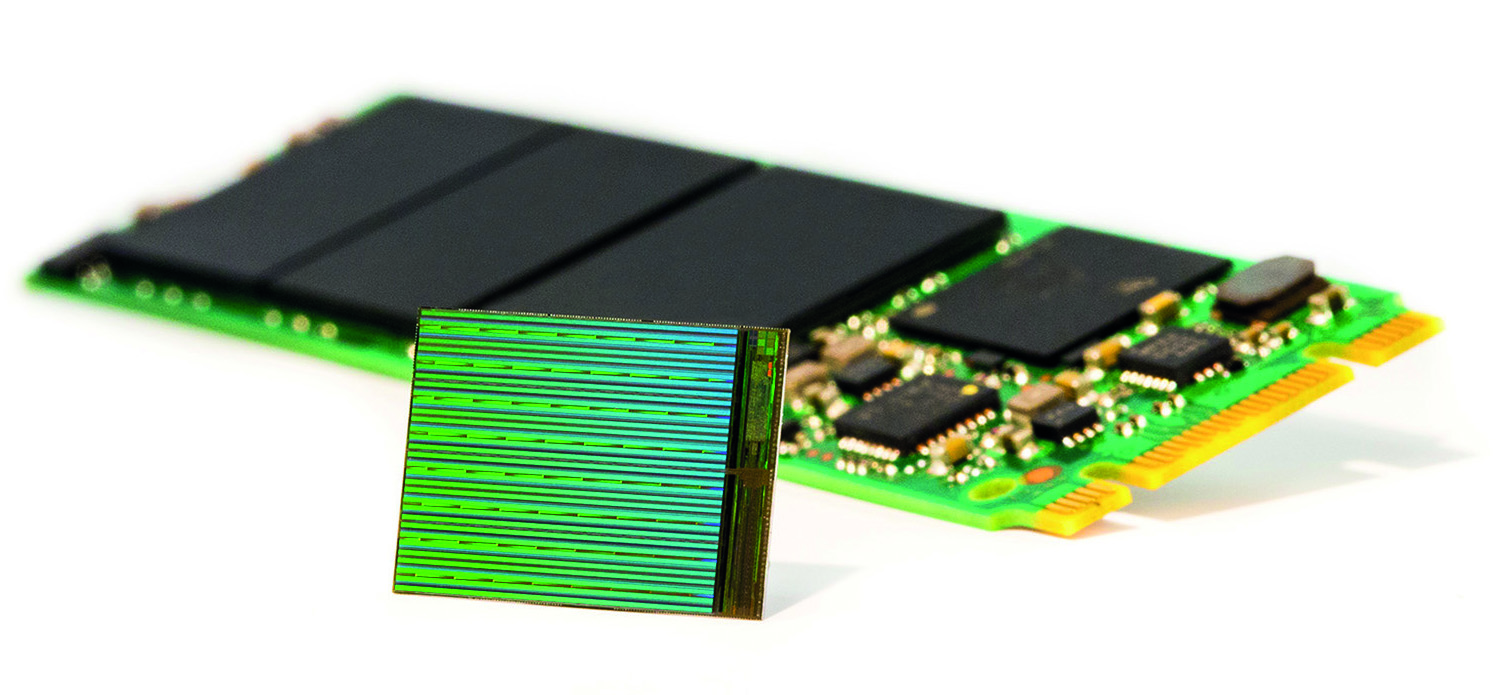

Not many years ago, SSDs typically came in tiny capacities; today, you can buy drives in sizes up to 4TB. That's largely thanks to the advent of 3D NAND technology, which stacks memory cells on top of each other, making it possible to squeeze huge capacities into small chips.

Even so, solid-state drives are still much more expensive than their mechanical counterparts. If you're replacing a 1TB hard drive, you can save a worthwhile amount of money by downsizing to a 512GB SSD, or even a 256GB one. Avoid 128GB if you can.

You'll notice, incidentally, that SSD capacities don't always come in neat powers of two. For example, if you're looking for a half-terabyte drive, you might see drives advertising only 480GB or 500GB of space. Internally, these drives normally do contain 512GB of flash memory, but some cells are set aside for "overprovisioning". They can then be cycled into service as older cells wear out. Some drives come with software that lets you adjust how much space is set aside for overprovisioning.

Write tolerance and MTTF

SSDs don't need defragmenting. Indeed, disk optimisation tools can shorten the life of a solid-state drive, by subjecting it to large numbers of unnecessary write operations.

That cells wear out is an inherent limitation of the technology, but it isn't as disastrous as it might sound. The drive's on-board controller hardware keeps track of the state of the drive, and will warn you when its demise is imminent so you can copy off your data before it's too late.

The good news is, unless you're using it continuously for heavy database operations, your SSD will almost certainly outlast the computer it's installed in. The physical properties of flash memory cells are well understood, so manufacturers can confidently estimate the total amount of data that can be written to a drive before it's likely to fail - a statistic known as "write tolerance". A typical drive might offer a tolerance of 200TBW (terabytes written), meaning you could write 50GB to the drive every day for ten years without hitting the advertised limit.

The other measure of endurance is MTTF, or "mean time to failure" - an engineering prediction of how many hours the drive will work for before giving up the ghost. Most drives promise at least 1.5 million hours, which is equivalent to 171 years. In other words, it's another thing you probably don't need to worry too much about.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Encryption

Some SSDs come with built-in hardware encryption. This is a great feature to have - since the encryption handled by the drive's own controller, it ensures that absolutely everything you write to the drive is protected, and there's no performance hit.

However, encryption isn't enabled by default. Or, to be strictly accurate, by default files are encrypted as they're written to disk, then automatically decrypted again as you access them - so it's as if you had no protection at all. If someone else hops onto your PC or steals your laptop, your files will be wide open.

To make your drive's encryption feature useful, you need to set up authentication on your PC. There are various ways to do this: if your drive is compliant with the Opal 2 standard then your BIOS may allow you to create a password for it. Once you've done this, you'll need to provide the password in order to boot from the disk; without it, the drive is completely inaccessible, even if it's removed and hooked up to another PC.

If you're running a "Professional" edition of Windows then you can alternatively use the built-in BitLocker encryption system: as long as your SSD supports Microsoft's eDrive standard, BitLocker will use its built-in encryption for maximum security and performance.

TRIM

Like the SLC versus MLC debate, TRIM used to be a hot topic in the world of SSDs. To understand why, it's necessary to know a little bit about how SSDs write to their flash memory cells. For technical reasons, it's not possible to update a single cell in isolation; the controller has to rewrite the entire virtual data block containing the cell. The more data that happens to be stored in that block, the more there is to rewrite: in an extreme case, you could end up writing 512KB of data every time you wanted to update a single bit. As you can imagine, this has a pretty serious effect on performance.

TRIM is an operating system feature that tells the SSD which bits of data are no longer needed, so it doesn't bother rewriting them and thus keeps slowdown to a minimum. TRIM is incorporated into all recent releases of Windows, but it's not supported on Vista or older systems. If you're upgrading an ancient PC, you might need to use the manufacturer's own software to manually run TRIM from time to time, to ensure your SSD isn't being slowed down (and worn out) by continually rewriting junk.

This article originally appeared in PC Pro issue 275

Darien began his IT career in the 1990s as a systems engineer, later becoming an IT project manager. His formative experiences included upgrading a major multinational from token-ring networking to Ethernet, and migrating a travelling sales force from Windows 3.1 to Windows 95.

He subsequently spent some years acting as a one-man IT department for a small publishing company, before moving into journalism himself. He is now a regular contributor to IT Pro, specialising in networking and security, and serves as associate editor of PC Pro magazine with particular responsibility for business reviews and features.

You can email Darien at darien@pcpro.co.uk, or follow him on Twitter at @dariengs.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Qsan XCubeNAS XN5012RE review: Powerful data protection

Qsan XCubeNAS XN5012RE review: Powerful data protectionReviews The app choice is basic, but this expandable NAS delivers enterprise-level data protection at an SMB price

By Dave Mitchell Published

-

Best NAS drives: Which network storage appliance is right for you?

Best NAS drives: Which network storage appliance is right for you?Best The perfect NAS drive for every use case, from a home office all the way to the enterprise

By Connor Jones Last updated

-

Fujitsu SP-1425 review

Fujitsu SP-1425 reviewReviews A slick combination of ADF and flatbed let down by software limitations and a comparatively high price

By Adam Shepherd Published

-

Brother ADS-3000N review

Brother ADS-3000N reviewReviews It lacks wireless and cloud support, but this speedy network desktop scanner has impeccable paper handling and a low price

By Dave Mitchell Published

-

Brother HL-L8360CDW review

Brother HL-L8360CDW reviewReviews Average colour quality, but this expandable and well-connected A4 colour laser delivers good speeds and top-notch security measures

By Dave Mitchell Published

-

Xerox VersaLink C400DN review

Xerox VersaLink C400DN reviewReviews A feature-rich and affordable A4 laser with superb colour quality, tough security and an app for every occasion

By Dave Mitchell Published

-

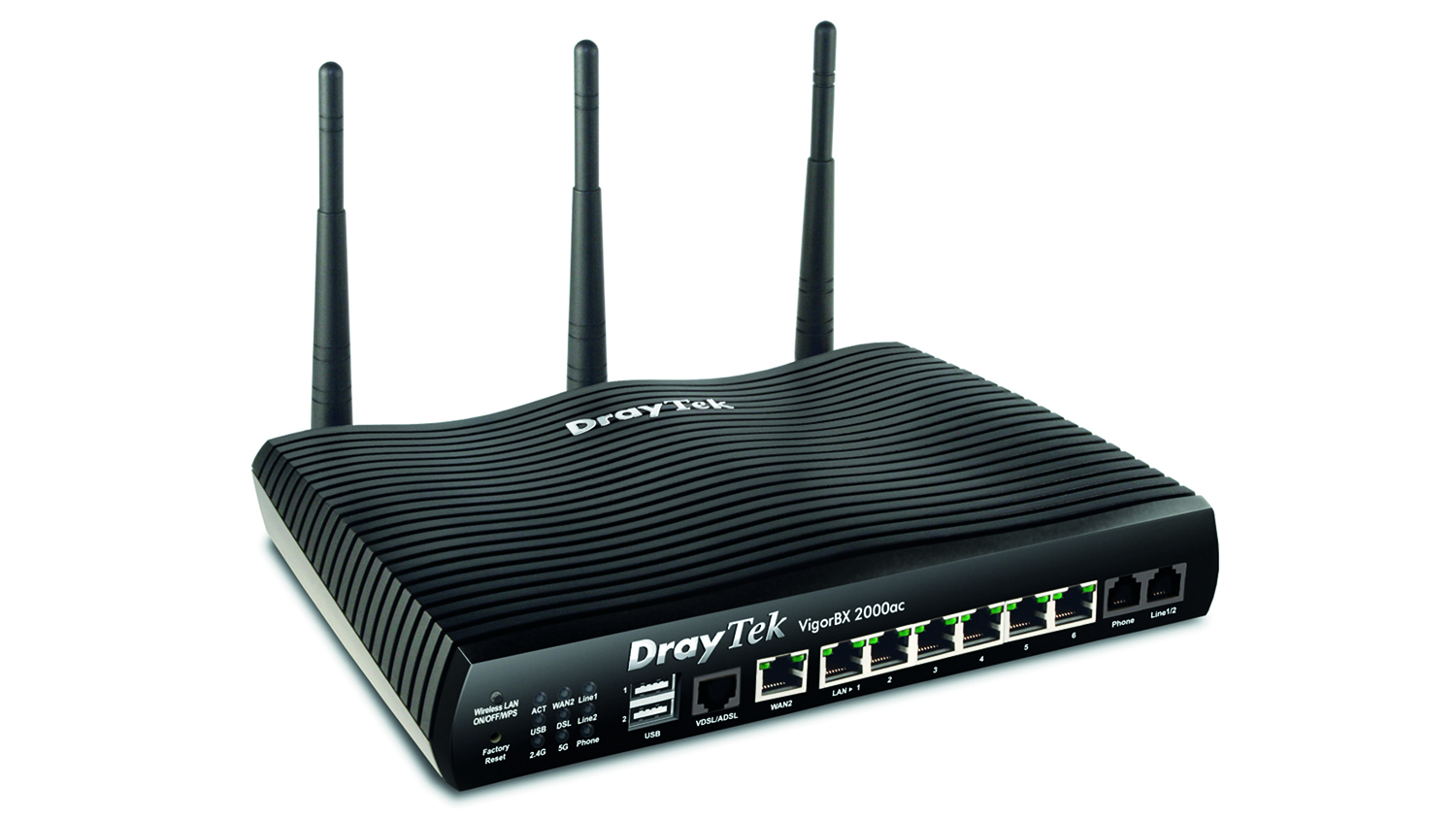

DrayTek VigorBX 2000ac review

DrayTek VigorBX 2000ac reviewReviews A feature-packed router and IP PBX combo that’s ideal for SMBs seeking an all-in-one networking solution

By Dave Mitchell Published

-

Two ports, no waiting? The pros and cons of link aggregation

Two ports, no waiting? The pros and cons of link aggregationIn-depth Link aggregation sounds like an easy way to double your NAS speeds – but it’s not as simple as it sounds

By Darien Graham-Smith Published