International Women's Day: Do diversity quotas help or hinder woman in tech?

As we celebrate women in technology, we examine the value of diversity quotas

Women in tech are divided over whether gender quotas are the right way to get more females into STEM careers.

There has arguably never been more attention focused on addressing the technology industry's diversity issue, from getting more girls into STEM, shining a light on sexual harassment in the workplace, addressing the gender pay gap or simply increasing the number of female executives in companies.

Implementing mandatory diversity quotas has long been put forward as one solution, but it is by no means a perfect answer. While they are a quick way to get women into tech roles, some fear that people will not believe women get these jobs based on their abilities.

Emer Timmons, president of BT Global services UK, tells IT Pro: "We've moved on from [the idea of] using quotas. Not one girl out there wants to be sitting in a job because she fulfilled a quota. We as women want to be there because we know we've got the capability, and in some respects we do a better job than our male equivalents in certain roles."

Speaking at the Inspiring Women panel event hosted by Hewlett Packard Enterprise and CBI, Miriam Gonzlez-Durntez, lawyer and partner of international legal practice at Dechert, strikes a more balanced note, saying: "I am personally a reluctant supporter of temporary quotas because my legal mind says there is something really wrong with addressing a discrimination with another discrimination. However, after thinking about it from a lot of different angles I'm willing to compromise."

Without quotas, there are already more women on FTSE 100 boards than ever before (26 per cent in October 2015), according to figures published in a report authored by Lord Mervyn Davies, and the number of all-male boards has also fallen dramatically since 2011.

While European countries such as Norway and France chose to introduce quota regimes, the UK instead uses a targets-based system, though it is not enforced. Norway leads the way with 35.1 per cent of board members now being women, with France following close behind with 32.5 per cent.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Meanwhile, the percentage of women occupying board seats at UK stock index companies stood at an average of 22.8 per cent, figures from 2014 published by Catalyst showed. Norway stood at 35.5 per cent, and France at 29.7 per cent.

"Targets are a good way to shine a light on the issue but I think we have to make them meaningful and memorable, and there has to be some governance around how we are managing the process of targets," says Jacqui Ferguson, SVP and general manager for HPE's enterprise services in the UK, also speaking on the panel.

"I want to be given opportunities because I deserve them, not because I'm making up the numbers. The worst thing you can do is put a woman in a position where she fails, where she doesn't have that support around her and lacks in confidence."

Last year, leading industry figures gathered in London to discuss practical ways to get more women into science, technology and engineering roles, with opinions over mandatory quotas decidedly split.

Some believed strongly that such a move would attach a stigma to those women employed or promoted in order to meet the quota, others argued that short-term quotas could be used to 'make up the numbers' as the industry plays catch-up.

While the amount of women on boards is steadily increasing, the fact remains that the overall number of women in tech is dropping. Government data released last year revealed that, in 2012, just 26 per cent of workers in the sector were female, far lower than the national average of 47 per cent. Over 10 years, the number has fallen by seven per cent.

For Dr Sue Black OBE, founder and CEO of techmums and honorary professor at University College London, the pros of quotas outweigh the cons.

She tells IT Pro: "When I was younger I thought quotas were a bad idea, but the older I get the more I just think we need something like quotas so that we can make a change. We need a period where we use quotas to get more women in or more diversity happening. Then, when we've got more diverse boards, we won't need the quotas anymore because everyone will have realised it's better if you have more diversity on the board."

However, Lynn Collier, chief operating officer for UK and Ireland at Hitachi Data Systems, dismisses quotas as a "quick fix", saying businesses need to take responsibility and promote more women, "especially if they want to enjoy the business benefits that accompany gender diversity".

Cisco UK and Ireland's CTO, Dr Alison Vincent, adds: "Quotas are a waste of space. It's a shame we need them to get companies measured on it I think there's much more value in building on and publishing the research that shows a direct correlation between diversity and business success."

Looking at the positive results countries that have introduced mandatory quotas are seeing, it is tempting to declare them an outright triumph for diversity. But, as many leading women in tech point out, could this lead to resentment in the long-term, and cause women to be put in a position before they are ready, setting them up for failure?

With issues such as a lack of girls studying STEM subjects limiting the talent pool, and women suffering from unconscious bias once in the workplace, quotas may be one short-term solution to a very long-term problem.

Caroline has been writing about technology for more than a decade, switching between consumer smart home news and reviews and in-depth B2B industry coverage. In addition to her work for IT Pro and Cloud Pro, she has contributed to a number of titles including Expert Reviews, TechRadar, The Week and many more. She is currently the smart home editor across Future Publishing's homes titles.

You can get in touch with Caroline via email at caroline.preece@futurenet.com.

-

Why keeping track of AI assistants can be a tricky business

Why keeping track of AI assistants can be a tricky businessColumn Making the most of AI assistants means understanding what they can do – and what the workforce wants from them

By Stephen Pritchard

-

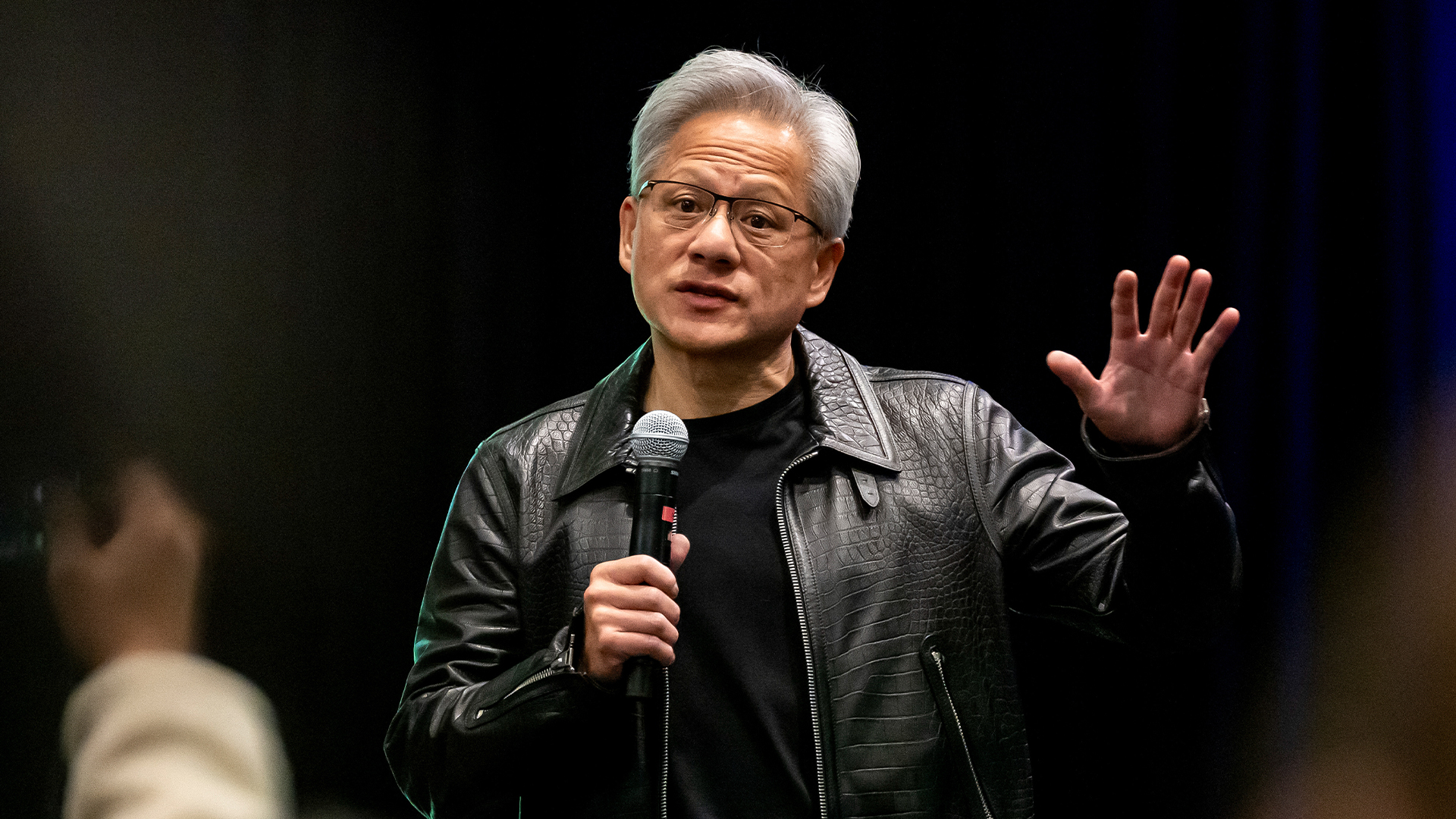

Nvidia braces for a $5.5 billion hit as tariffs reach the semiconductor industry

Nvidia braces for a $5.5 billion hit as tariffs reach the semiconductor industryNews The chipmaker says its H20 chips need a special license as its share price plummets

By Bobby Hellard

-

International Women’s Day: Where now for women in tech?

International Women’s Day: Where now for women in tech?Opinion Women have a long history of making strides in technology, yet recognition – and fair treatment – remain elusive

By Jane McCallion

-

Awards celebrate 2017's women in tech

Awards celebrate 2017's women in techNews Software engineers, developers, security experts, students and lecturers were all recognised for their achievements

By Clare Hopping

-

TechWomen50 Awards releases 100-strong shortlist

TechWomen50 Awards releases 100-strong shortlistNews Women in tech shortlist recognises the achievements of techies across Britain

By Joe Curtis

-

500 Canada 'to kill startup fund after US founder's sexism scandal'

500 Canada 'to kill startup fund after US founder's sexism scandal'News The startup fund's potential investors didn't want Dave McClure involved at all - report

By Zach Marzouk

-

Startup launches campaign to place 1,000 women in tech by 2020

Startup launches campaign to place 1,000 women in tech by 2020News Structur3dpeople's initiative will help build up the skills of women in tech

By Clare Hopping

-

Why are women such a problem?

Why are women such a problem?Opinion We’ve reached the end of our spotlight on women in tech month, but why are we even having to talk about this stuff?

By Maggie Holland

-

Fujitsu workers stage 48-hour strike over gender pay gap

Fujitsu workers stage 48-hour strike over gender pay gapNews 300 Fujitsu employees go on strike in Manchester to protest against jobs, pensions and pay

By Dale Walker

-

Q&A: Sarah Lewin, Esri UK

Q&A: Sarah Lewin, Esri UKIn-depth How GIS gives women a route into the male-dominated tech sector

By Jane McCallion