How AI-powered tech can improve digital accessibility

With COVID highlighting the widening digital divide for people with disabilities, can AI come to the rescue?

Despite one billion people, or roughly 15% of the global population, living with a disability, there remains much work to be done by governments and businesses to close the digital access divide that exists today.

This digital divide has become even more prominent with the emergence of COVID-19, with differently-abled people, like everyone, suddenly forced to grapple with the challenges of social distancing and lockdowns. Technology eased this strain for many of us, but research by South Korean academics found the surge in mid-pandemic internet usage wasn’t mirrored by people with disabilities. Differently-abled people were also less likely to be aware of, utilise or perceive the usefulness, of digital services.

Although there was no need for direct personal contact in accessing many public services, such as information on COVID-19 cases and the location of testing clinics, people with disabilities still faced barriers due to a lack of digital literacy and access. With the divide feeling wider than ever, innovators are increasingly looking to artificial intelligence (AI) to narrow the gap.

Digital barriers

From studying to accessing services and communicating, recent technological advancements have transformed every aspect of day-to-day life. People with disabilities, however, still face challenges in accessing the systems that have become more integral to our way of life. Even before COVID-19, differently-abled people used the internet, and other digital systems, at a level that was much below the standards people without disabilities have come to expect.

People with visual impairments, for example, use screen readers, applications that provide computer-synthesised speech output, to access web content. Their screen readers, however, find it problematic to convert text-to-speech if designers haven’t included appropriate alt-text tags on graphics, forms, tables, or links.

People with motor impairments, too, who had zero or limited use of their fingers or hands face considerable barriers due to cluttered layouts on websites, buttons or links that are too small. They also face difficulties using a pointing device, like a computer mouse. Finally, people with cognitive impairments like autism, dementia, or traumatic brain injury face significant trouble in understanding the design, layout, and navigability of websites that aren’t accessible.

Wielding AI for good

The use of AI – comprising mixed reality, speech recognition, natural language processing (NLP), and automation – has become more common in homes and offices, Soumendra Mohanty, chief strategy officer and chief innovation officer with Tredence, tells IT Pro.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

“Today, if a patient calls a clinic, they get the opportunity to interact with virtual doctors and not just human doctors,” he says. “While a virtual doctor may not replace an actual human doctor, it could give a patient the confidence that they were able to interact with an entity whose body language was similar to a real human doctor.

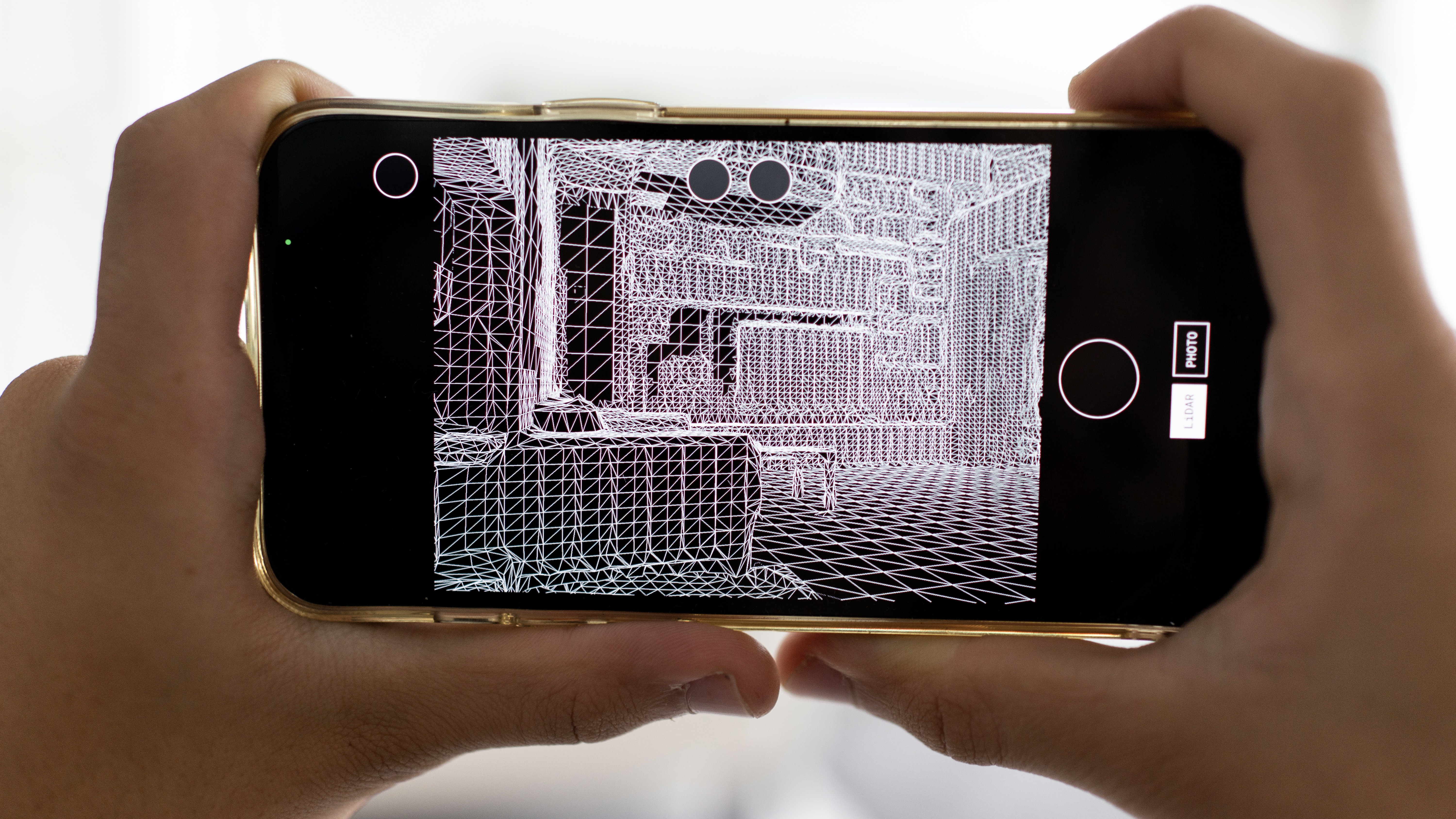

“People with visual disabilities can take the help of advances in AI relating to gesture/touch or voice-enabled products and services. On the other hand, people with hearing disabilities can use gesture-enabled interventions using AR/VR apps. Finally, people with speech-related disabilities can use gesture/touch interventions in AR/VR apps.”

People with visual impairments, indeed, face severe accessibility challenges and, at times, are faced with the hard decision of giving up on their educational aspirations altogether, adds Mousumi Kapoor, the founder and CEO of Continual Engine, an accessibility systems provider. “The use of computer vision, NLP, machine learning, and AI can make complex documents and images readily accessible to people suffering from visual impairments,” she says.

“Earlier on, developers and designers needed to manually make image content accessible by physically authoring meaningful alt text (alternate text) for images. With the help of software products powered by AI, however, this process is automated, saving up to 60% of the time in comparison to doing the same processes manually. Besides enabling people with visual disabilities to get access to content that was earlier inaccessible to them, the use of such technologies helps in making content accessible to all.”

Building bridges with technology

One of the biggest differences AI-powered tech can make for people with disabilities is allowing them to form meaningful relationships with other people on a similar disability spectrum. When it comes to online dating, Michele Abraham, founder and CEO of Quiver Dating, tells IT Pro, people with disabilities are at a disadvantage.

“Most, if not all, popular dating apps do not cater to people with visible and invisible disabilities,” she says. “That is one area where AI in conjunction with AR virtual dating platforms can truly make forming meaningful relationships that much easier for people with disabilities.”

Online dating, however, is just one of many kinds of platforms using AI to improve access for people with disabilities. There are several others that fall into this bracket, including Moment.AI, a startup that’s striving to develop an in-vehicle AI system that can detect, monitor and analyse whether a driver is fit to continue driving. The firm aims to create image-based and video-based datasets using simulators to allow AI systems to pre-empt stress-induced medical events, such as strokes and seizures, before they lead to accidents.

Perhaps a little more widely known, Neuralink, founded by Elon Musk in 2016, aims to use a brain implant to allow humans to interface wirelessly with computers and mobile phones. The fully-implantable chips intends to help people with paralysis, as well as neurological disorders and disabilities in the future.

Finally, ObjectiveEd’s Braille AI Tutor, developed in conjunction with Microsoft, is a teaching aid for students who suffer from visual disabilities. This product uses gamification to help children learn through speech recognition with the help of a braille display.

Whether AI-powered tech will meaningfully improve conditions for people living with disabilities, is one that hinges on how robust and accessible the technology becomes. Thanks to recent developments, however, the future certainly appears brighter than it ever has.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Fixing the faltering AI transcription ecosystem

Fixing the faltering AI transcription ecosystemIn-depth Highly in-demand services that make up this ecosystem are riddled with problems, raising negative consequences for productivity and accessibility

By John Loeppky Published

-

We should celebrate accessibility tools, not hide them away

We should celebrate accessibility tools, not hide them awayOpinion Whether in macOS, Apple Watch, Windows 11, or other platforms, there are swathes of great accessibility features available to everyone

By Jon Honeyball Published

-

Cryptocurrency: Should you invest?

Cryptocurrency: Should you invest?In-depth Cryptocurrencies aren’t going away – but big questions remain over their longevity, the amount of energy they consume and the morals of investing

By James O'Malley Published

-

FCC commissioner calls for big tech to help bridge digital divide

FCC commissioner calls for big tech to help bridge digital divideNews FCC’s senior Republican wants the likes of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google to help pay for broadband expansion

By Mike Brassfield Published

-

Social networking use jumps in the UK

Social networking use jumps in the UKNews A new Ofcom report has shown we still love social networking - but many aren't even online yet.

By Nicole Kobie Published