We asked ChatGPT to write our Christmas cards. It didn't go well

The internet’s new favourite AI tool can produce powerful results, but these are firmly rooted in the uncanny valley

Art produced by artificial intelligence (AI) models has quickly gained popularity throughout the year. Driven in part by its ease of use, and coming off the back of years of generative AI development, AI art has become a defining subject in the tech conversations of 2022.

The exact enterprise use cases of ChatGPT and DALL·E are still unclear and, at present, the models are in a kind of public testing phase as people and businesses explore the potential and limitations of AI art as it stands.

How does generative AI work?

A mainstay throughout the year has been DALL·E 2, OpenAI’s model for generating images based on a user prompt. DALL·E works by translating prompts into machine readable keywords, which are weighted against a constantly-updating model that recognises images.

To achieve this, it uses a model called contrastive language-image pre-training (CLIP), which has been trained on many millions of images to determine the vector spaces and dominant features of images. This means rather than simply knowing what an image is, CLIP allows the AI model to identify how much of the image any given prompt relates to in order to work out each image’s individual features and descriptors.

By reverse-engineering this same model, DALL·E can generate images with a given percentage dedicated to visuals it thinks the prompt implies. For example, the prompt ‘dog on a chair’ might inform DALL·E that some of the image – say, a third – has to contain a chair, as its large-model training has suggested. Through training with huge datasets and, after a long development process, OpenAI set these models loose to the public through their website, where one can generate a set number of images for free every month.

In addition to its increasing popularity for generating images, OpenAI’s chat generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) is able to generate tracts of text based on a prompt. For example: In 2022, AI art is becoming increasingly popular. Some AI art is created by algorithms that randomly generate images, while other AI art is created by humans who use machine learning to create art that is more sophisticated and lifelike. Some people believe that AI art is not really art, but others believe that AI art has the potential to be even more creative and expressive than traditional art.

Woodward it isn’t, but as this was generated in seconds based on the prompt 'write a paragraph about AI art in 2022’, it’s an example of how the model can be used to quickly produce text that passes a basic bar for grammar and covers any given topic.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

OpenAI has been through many iterations of its GPT natural language processing (NLP) algorithms and the current GPT-3 model has previously been withheld from public use over safety fears. The next iteration, GPT-4, is currently in development.

Happy AI-powered holidays

At IT Pro, this got us thinking: How can we test this technology in a manner that’s both thorough and festive? The answer, of course, was to combine DALL·E with ChatGPT to create a unique set of tech-themed Christmas cards.

Starting with artwork, it immediately became clear DALL·E was struggling with the term ‘Christmas card’, even when introducing the concept of Christmas into the visuals sparked by other elements of the prompts.

A Christmas card themed around virtual reality

It usually processed this by plastering a garbled (and frequently cut off) form of word art that read ‘Merry Christmas’ over the top of whatever it'd generated, as with the particularly vibrant virtual reality (VR) card.

The ‘cloud storage’ card was a little more in line with the art you’d expect to find on a Christmas card, but also basically nonsense. A very “Happy Cloaday” to you too, DALL·E.

Cloud storage Christmas card

The same cannot be said for the ‘CIO’ card, which was exciting but intense, festooned with garbled festive messages albeit far from ‘Christmassy’.

CIO Christmas card

To mix things up a little, we tried out a more generic prompt, ‘Hacker dressed as Jack Frost’, with the hope this could be a cheeky image to include on the front of an IT security team’s Christmas cards. We even mocked up a Grinch version.

“Cheeky” is not how I would describe the result, which is more than a little disturbing and reveals the limited extent to which DALL·E can generate believable human forms. Perhaps this is better as a Halloween card — it’s certainly not fit for any mantelpiece.

Hacker dressed as Jack Frost

Generative AI is rooted in the uncanny valley

Bringing in specific style descriptors appeared to rein in the madness somewhat, as seen in the ‘satirical cartoon’ prompt, which is the closest to anything you’d find on a real Christmas card. Yes, the face on the data centre technician is scrambled, and the text is gibberish, but the art style carried across is recognisable enough.

Satirical cartoon of Santa helping out in a data centre

The same is true of the watercolour painting example. In all likelihood, this comes back to CLIP, with each specific element introduced to the prompt changing the balance to which DALL·E can go wild with the other elements in the image. As what I’m assuming was a happy accident, the watercolour brush strokes omitted the faces of all but one of the ‘elves’ in this example, which ended up looking more like a stylistic choice than machine error.

Watercolour painting of software engineers dressed as elves, working on laptops in Santa’s workshop while a CEO dressed as Santa gives them a thumbs up

The charcoal engineer prompt did a more than passable job of recreating the physical medium, and could certainly pass as a photo of a sketch, rather than digital art. It’s only upon closer inspection that the illusion of the medium falls apart, with each stroke far too smooth to have been made with charcoal. The only real gripe with this image is that it ignored the Christmas theme — the engineer should have been climbing the North Pole, but we’ll just have to use our imaginations for that.

Charcoal sketch of a 5G technician climbing the North Pole

Remembering this balance and the statistical models that lie behind systems like ChatGPT and DALL·E is key to setting your expectations. It's not magic, and even if prompts are carefully phrased it doesn't make a bit of difference if there’s no training to support whatever use case you have in mind.

ChatGPT writes a haiku

Take this example of a ‘haiku’ prompt.

Prompt: A Christmas card written in haiku form, containing the word "Kubernetes".

A haiku is a Japanese form of poetry comprising seventeen syllables in three lines of five, seven, and five. This is not a haiku. Beyond that, it exposes the system's inherent weaknesses, as it falls back on cheap tricks when faced with a tricky prompt. Abandoning the metre and form of a haiku entirely, the model wasn’t even able to believably introduce the word “Kubernetes” into the output, instead choosing to dump the word front and centre in the out-of-place first line.

ChatGPT writes a corporate Christmas message

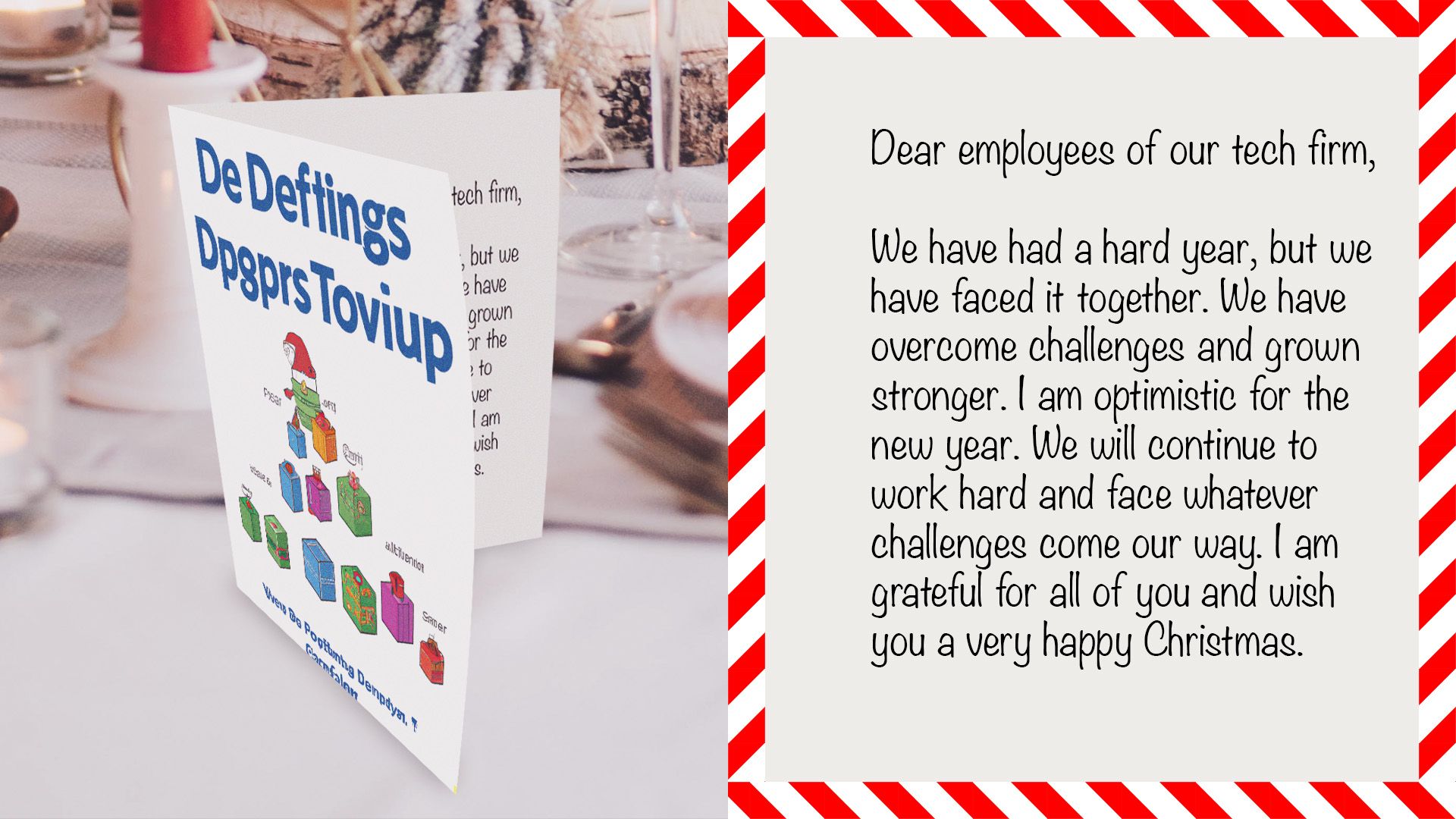

What if you’re not looking to send your Christmas card to one person, but a whole company of employees?

Prompt: Write a Christmas message to be shared via company email to a small tech firm with 20 employees, reflecting on the hard year the company has had but with optimism for the new year.

No one could call this heartfelt, and neither will anyone to raise a toast to the company’s CEO at the Christmas party. If it’s a bit vague and cliched, though, it’s a message that could believably be shared around via email at the end of the year, and not immediately recognisable as an AI-penned message.

For generative AI, results lie in the use cases

Considering the use case carefully applies to images too. Images the system can generate work best at a tiny scale. Take a step back from your screen, and some of the more passable images look ‘real’ enough. Look at them too closely, though, and you notice all the unsettling features that have become a trademark of AI art.

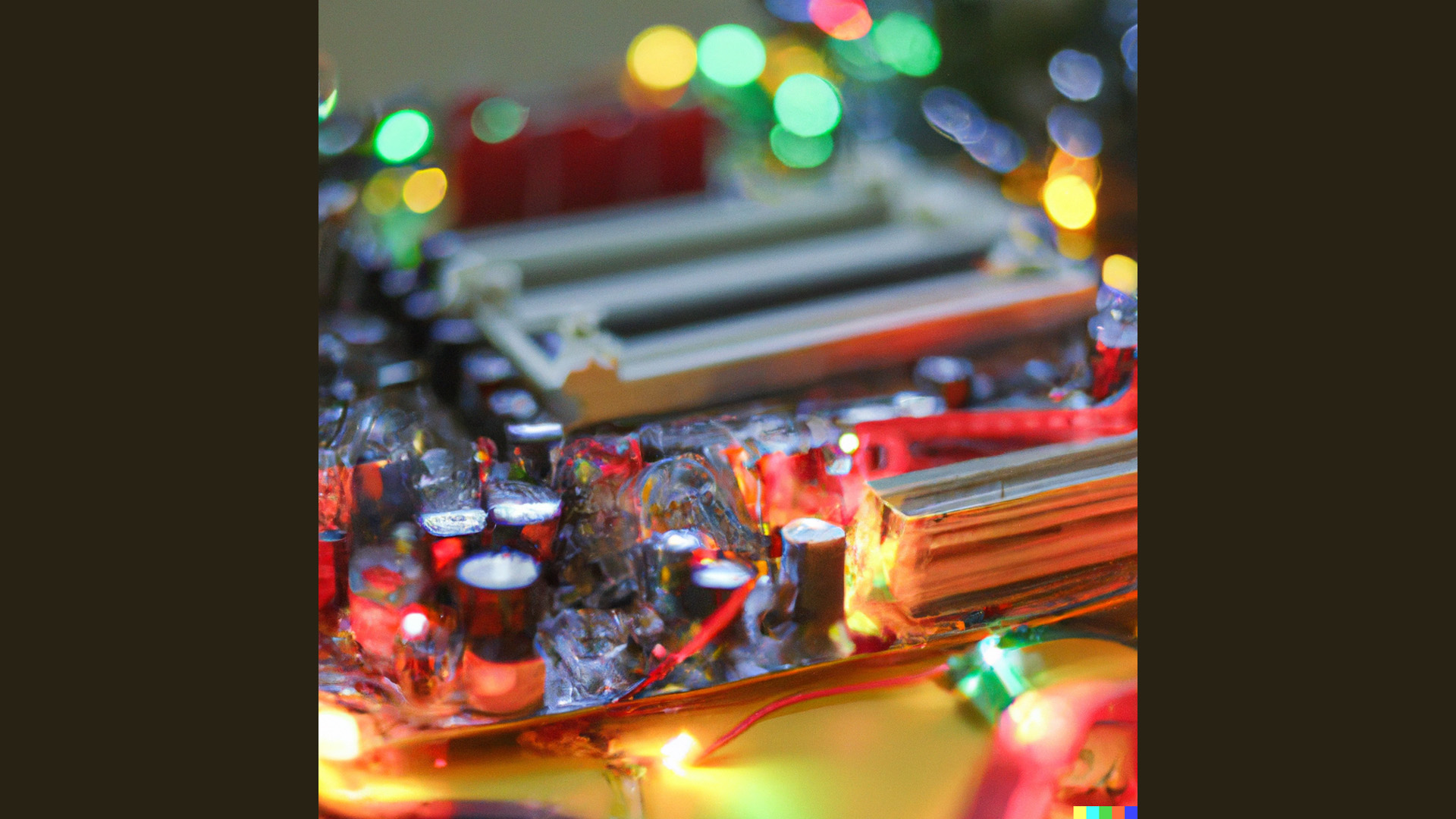

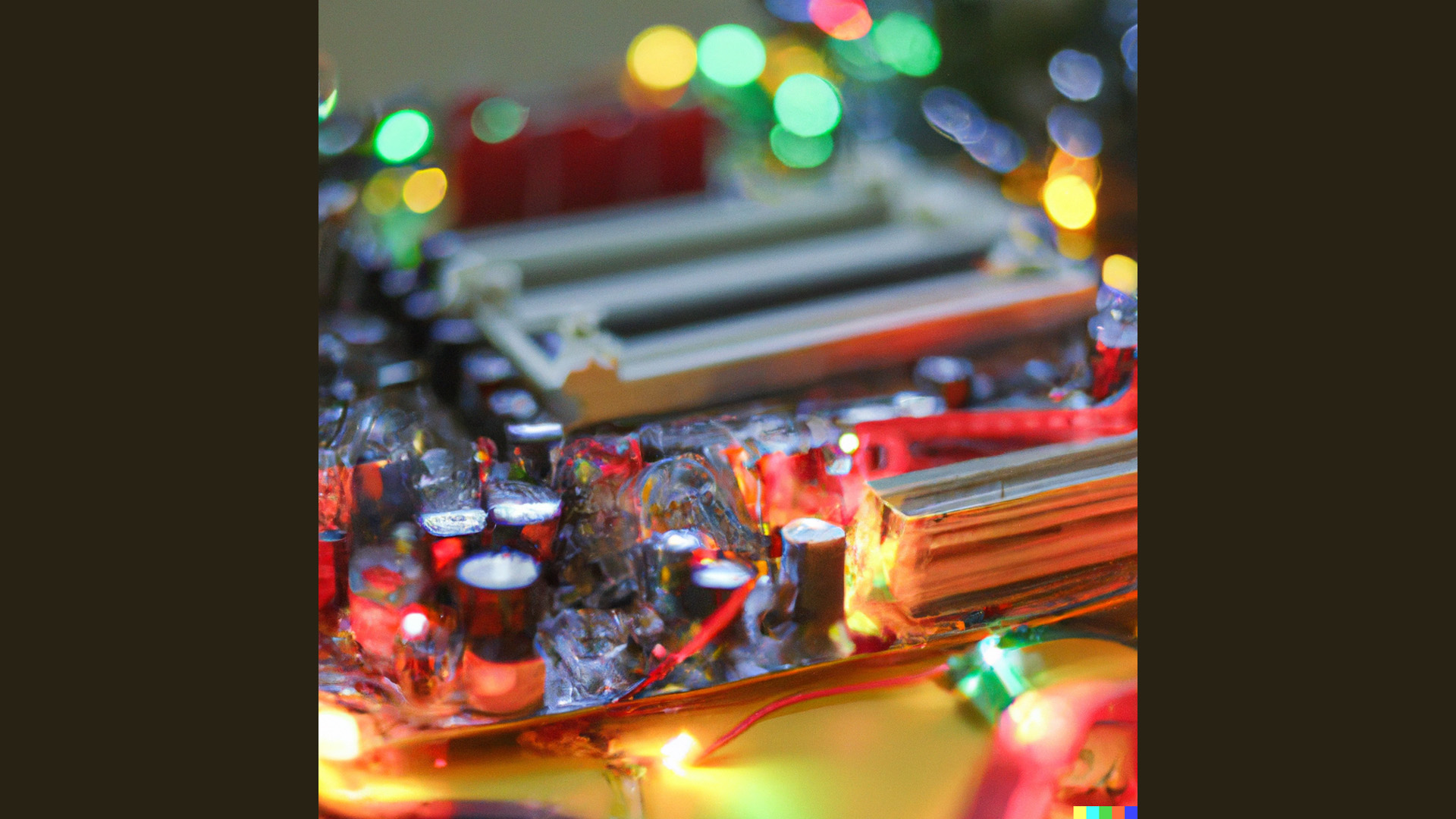

Take the ‘computer motherboard with Christmas lights’ prompt for example. If you’re reading this article on your phone, the illusion of the image may have held up longer for those viewing this on a monitor. Go back and zoom in on any of the fairy lights — or the circuitry of the motherboard itself — and you’ll see it’s really a mishmash of warped lines, hard edges and blurry stand-ins for detail.

A computer motherboard with Christmas lights

This also applies to the ‘charcoal sketch’, which looks roughly like charcoal from a distance, but up close appears plasticky, and instantly recognisable as a digital representation of the physical medium. Because AI image generation of this kind relies on ‘diffusion models’, in which random noise is edited pixel-by-pixel until it resembles the prompt given, DALL·E images tend to be wobbly on close inspection and fall apart under close scrutiny. This manifests most obviously in the programme's efforts at faces, which veer firmly into the ‘uncanny valley’.

Will generative AI replace creatives in the future?

We're not at all convinced AI has the necessary skill to supplant human artists. As we see, the models have a long way to go before they can begin to match the quality of human artists, and even the best outputs, a plethora of which can be found online, have strange flaws.

There are also strong ethical arguments against the widespread use of generative AI to create art, which include the damage it would cause to the value of creatives’ labour, and the legal grey area in which scraping work created by other people to train an AI model lies. For these reasons, AI art should not be seen as a revolution in the art world, nor a welcome tool for creatives, but a burgeoning area of development begging for close regulatory oversight. Arguments for legislation, such as the US’ proposed AI Bill of Rights, apply in every way to AI art, which challenges core human abilities to a degree that calls for greater debate.

Undeniably, ChatGPT is more convincing than DALL·E. Perhaps this is because there's no written equivalent of the uncanny valley and that, unlike the more disturbing results of DALL·E, ChatGPT outputs come across, at worst, as the handiwork of someone who isn’t a very capable writer.

That isn’t to say it’s a silver bullet for those out who want to write poetry for their office, but don’t have the knack for it. ChatGPT is worse than you, I guarantee, so keep up the practice. But with its ability to generate prose that only needs to be passable – such as a quick email response – NLP models may become more integrated into software like word processors. It could be used to generate generic product descriptions or company emails.

Above all else, humans will still need to play a key role overseeing AI creations; none of the artwork or text here could yet stand up on its own. If used for public-facing use cases, organisations will have to assign teams to manage the output of the likes of ChatGPT to make sure the AI-generated content cuts the mustard.

Rory Bathgate is Features and Multimedia Editor at ITPro, overseeing all in-depth content and case studies. He can also be found co-hosting the ITPro Podcast with Jane McCallion, swapping a keyboard for a microphone to discuss the latest learnings with thought leaders from across the tech sector.

In his free time, Rory enjoys photography, video editing, and good science fiction. After graduating from the University of Kent with a BA in English and American Literature, Rory undertook an MA in Eighteenth-Century Studies at King’s College London. He joined ITPro in 2022 as a graduate, following four years in student journalism. You can contact Rory at rory.bathgate@futurenet.com or on LinkedIn.

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Redis unveils new tools for developers working on AI applications

Redis unveils new tools for developers working on AI applicationsNews Redis has announced new tools aimed at making it easier for AI developers to build applications and optimize large language model (LLM) outputs.

By Ross Kelly Published

-

Future focus 2025: Technologies, trends, and transformation

Future focus 2025: Technologies, trends, and transformationWhitepaper Actionable insight for IT decision-makers to drive business success today and tomorrow

By ITPro Published

-

Digital transformation in the era of AI drives interest in XaaS

Digital transformation in the era of AI drives interest in XaaSWhitepaper Driving the adoption of flexible consumption XaaS models

By ITPro Published

-

Modernize your mainframe application environment for greater success

Modernize your mainframe application environment for greater successWhitepaper Successful modernization strategies require the right balance of people, processes, technology, and partnerships

By ITPro Published

-

B2B Tech Future Focus - 2024

B2B Tech Future Focus - 2024Whitepaper An annual report bringing to light what matters to IT decision-makers around the world and the future trends likely to dominate 2024

By ITPro Last updated

-

Let's rethink customer service

Let's rethink customer servicewhitepaper Discover new ways to improve your customer service process

By ITPro Published

-

The power of AI & automation: Productivity and agility

The power of AI & automation: Productivity and agilitywhitepaper To perform at its peak, automation requires incessant data from across the organization and partner ecosystem

By ITPro Published

-

The guide to digital worker technology to improving productivity

The guide to digital worker technology to improving productivitywhitepaper Learn how to turn your workforce into a talent force

By ITPro Published

-

Operational efficiency and customer experience: Insights and intelligence for your IT strategy

Operational efficiency and customer experience: Insights and intelligence for your IT strategyWhitepaper Insights from IT leaders on processes and technology, with a focus on customer experience, operational efficiency, and digital transformation

By ITPro Published