Why 2024 won’t be the year of AR, VR or any kind of immersive tech

Whether it’s Apple’s Vision Pro or Meta’s continued metaverse push, many predict we’re at the turning point for mixed reality, but there’s little evidence to show for that

There are few technologies that have stumbled such a slow and meandering path as display headsets. Be it virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), or extended reality (XR), the final reality has proved underwhelming. But expectations continue to be high, with some suggesting 2024 as the year that changes everything.

Despite Facebook-parent Meta investing in VR, and Apple’s newly released Vision Pro gaining traction, we’ve been promised such glory before. Spanning Ivan Sutherland’s first AR headset in 1968 to the Oculus Rift in 2012 – and beyond – with the HoloLens 2 and Google Glass making an impact in the AR space, the history is somewhat disjointed.

But it’s something both Meta and Apple are hoping to disrupt – and no wonder when analysts keep touting a massive potential market, with analyst firm Technavio predicting AR will grow by 28% to $157 billion by 2027.

Duncan Stewart, director of technology, media, and telecommunications research at Deloitte Canada, however, doesn’t think 2024 is the year that it takes off. “Both [AR and VR] have been predicted to be large markets growing at 50–100% for years now,” he says.

“This has been going on for nearly a decade, where people have been saying this is the year where it’s going to be huge – and it keeps not happening.”

Why mixed reality technology is far from ready

VR has improved, but headsets have become more expensive, notes Stewart. “This limits consumer demand, it limits enterprise demand,” he says, noting that’s especially true during tough economic times. “At the start of 2022, people were looking for VR sales to grow strongly, but they declined about 20%.”

AR is an even tougher problem to solve as the technology still needs work. Users are promised constant access to their data and updates at the glance of an eye – but are instead saddled with heavy glasses with short battery life and unimpressive displays.

Get the ITPro daily newsletter

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

“There are AR goggles that are thinner and lighter and don’t give you motion sickness, but the problem is they don’t do much – they can display text, and colored images, but only if it’s not bright outside,” Stewart says. “The resolution is not that high and color saturation isn’t good.” One solution could be micro-LEDs, which may enable bright, clear, and colourful AR glasses without using much power – but that’s likely many years away. “They’re incredibly hard to scale,” Stewart says.

The Lumus Z-Lens 2D waveguide glasses delivered an AR surprise at CES 2023

Matthew Ball, venture capitalist and author of The Metaverse And How it Will Revolutionise Everything outlined in a blog post that AR glasses need to weigh in at less than 150g to be worn all day like normal “dumb” glasses, but they need to do so while carrying their own battery. All of this before you factor in displays, speakers, microphones, and sensors; all while analyzing and understanding what the person sees in the real world and digitally. It’s a lot of work crushed into a tiny amount of space.

This is why enterprise devices are expensive and used for short periods of time. Ball points to surgeons trialing devices where most of the hardware is offloaded to computers under the table, in the same way that Sony’s VR2 headset is powered by a PlayStation console. If there was one ray of hope, it was to be found at CES. There, Israeli company Lumus demoed a lightweight pair of glasses with a 2 x 2K resolution that was comfortable to wear and displayed sharp, bright images.

Unpicking big tech’s plan for future hardware

After changing its name to Meta, the company formerly known as Facebook remains all-in on the metaverse. Well, 20% in. In November 2022, Zuckerberg responded to investor concerns that Meta was sinking too much money into its Reality Labs division with the response that “about 80% of our investments – a little more – go towards the core business”.

He added: “So still the vast majority of what we’re doing is, and will continue to be, going towards social media for quite some time until the metaverse becomes a larger thing.”

RELATED RESOURCE

Download this eBook to learn how VR can overcome creative challenges and transform every part of the design process for research and development teams.

In March, Zuckerberg showed off to employees its plans for VR and AR, planning to release an updated, thinner Quest 3 headset that also features cameras on the front for augmented features, rather than fully immersive viewing – similar to its high-end Quest Pro.

Beyond that, Meta plans to release a follow-up to its Ray-Ban smart glasses, which can take photos via voice controls and share what you capture. Future versions, due in 2025, can display text messages and connect to a “neural interface” to add hand gestures and one day type as if on a keyboard. But true AR glasses aren’t expected to arrive until at least 2027, and enthusiasts will be targeted first rather than mainstream audiences. Apple, meanwhile, has just released its Vision Pro, although it’s unclear how well this has been received and to who, exactly, it was originally pitched.

Perhaps they should be concerned – if Google’s Glass is anything to learn by. The company now known as Alphabet unveiled Glass in 2012 as a beta product to be sold directly to developers, despite internal concerns the product wasn’t ready. And it clearly wasn’t, never going on wide release, it was yanked from sale in 2015. It subsequently returned as an enterprise product, but that too will no longer be sold as of March.

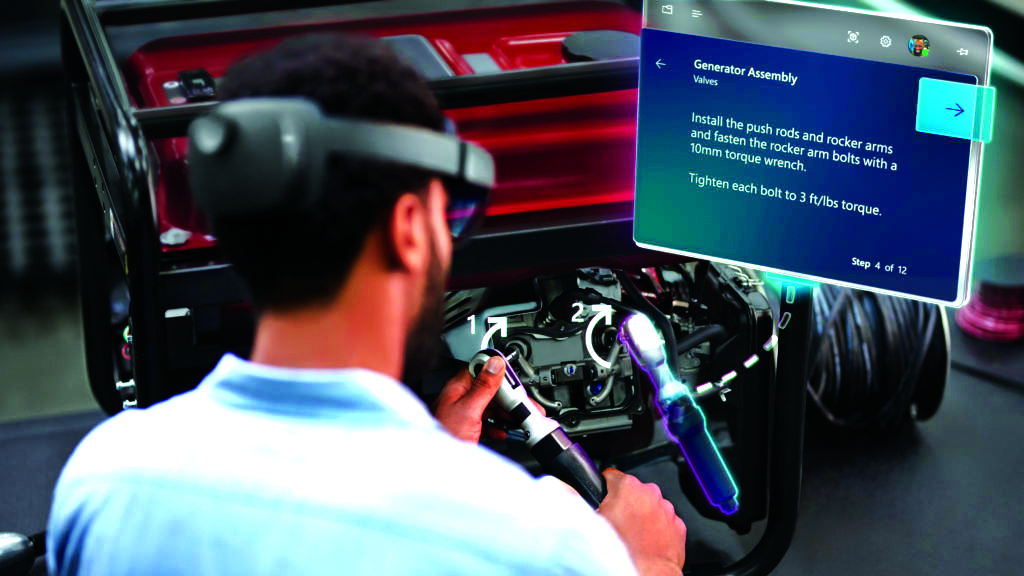

In the meantime, researchers continue to work with existing headsets to find ways to solve problems and add features. Academics at MIT developed an app for Microsoft Hololens that lets the user “see” an object marked with an RFID tag that is beyond their range of sight, a tool that could be useful for warehouses or in manufacturing, to find the right part or component. And in yet another March 2023 announcement, Snap unveiled AR Enterprise Services, a platform for building AR tools. That includes a Shopping Suite that makes it easier to build apps for customers to try on clothing using a smartphone.

How mixed reality has found an industry niche

VR headsets continue to muddle by in the consumer market, but things look more promising when you switch to the business market. Enterprises have found intriguing ways to make use of VR for training, simulations, and medical applications. Plus there’s a growing use case for exploring digital twins, Stewart believes, letting you walk through a digital version of a plant or hospital, for example. Where VR isn’t being used is in meetings – as video calls seem to suffice for most office workers.

“There are some applications where it’s a good thing, but putting on a headset isn’t what most people want to do to make a call,” Steward says, noting that goggles still make some people feel ill. At Mobile World Congress 2023, a demo being shown to a colleague couldn’t go ahead because the company rep didn’t like wearing the headset as it made him throw up. “If you want to know why it hasn’t taken off, the fact that a company can’t do a demo because they don’t like the technology tells you more than any number of research reports.”

The HoloLens 2 has become a specialist enterprise tool in the manufacturing sector

The enterprise market has been held back by hardware fragmentation, says Rolf Illenberger, CEO and founder of enterprise software company VRdirect. Differing features make it possible but difficult to develop content for multiple headsets – and it means limiting development to the lowest common denominator, rather than whizzy features and top-end specs. Procurement is also challenging when manufacturers yank support with little warning.

That happened with one VRdirect client, a major carmaker that bought 150 Oculus Go headsets only to have Meta ditch support a few months later. “The development curve is on an exponential growth rate,” says Illenberger. “The next device generation feels so much more improved, but you have outdated devices in a fairly short time period.”

Geopolitics also comes into play. One of the most popular headsets is made by Pico, recently acquired by China’s ByteDance, which also owns TikTok, the social network under pressure by US politicians. Chinese PC manufacturer Lenovo is also set to release its VR headset soon. “We’re going to head into a China vs US situation with this new technology,” said Illenberger. “For European companies, the situation is a nightmare because you don’t trust Meta – and your alternatives are from China.”

What is the future of AR, VR, MR, and XR?

As the headset market evolves, acronyms are becoming more jumbled. Facebook’s Quest Pro has front-facing cameras to allow some AR capabilities, for example. “I think we have to be realistic about these MR features on the road to AR,” says Illenberger, with a nod to Apple’s Vision Pro in the way it’s combining different kinds of interaction.

Like Stewart, Illenberger agrees that true AR is years away. “AR has the capacity to replace smartphones as the number one device that humans are using to interact with technology – but that’s probably a 2030 thing,” Illenberger predicts.

One upside is that gives the technology industry plenty of time to get the content right for these devices. “It’s not just the technology, you have to have a compelling ecosystem,” says Illenberger. Apple is obviously a master at ecosystems, and it’s clear Meta has tripped up here with its early interpretation of the metaverse, with low numbers of returning users to its virtual space, Horizon. “What does that say? It’s probably not enough to just have a virtual space,” said Illenberger. “That’s not what people are attracted to – and Apple knows that.”

All that suggests that 2024 isn’t AR’s year and perhaps it won’t be for some time. Indeed, there’s a chance VR remains a niche gaming product and enterprise tool while AR fails to ever take off, argues Stewart – and it has nothing to do with technology, but with human reticence to wear something on our faces. After all, plenty of people, Stewart included, pay to have laser eye surgery to avoid wearing glasses.

“We, by and large, prefer not having things on our faces – is that an innate human behavior that means AR will never be as popular as the smartphone?” he wonders, admitting it’s impossible to know for certain until the hardware is ready. “The advantages of wearing these [headsets] will have to be strong to be as successful as smartphones.”

Freelance journalist Nicole Kobie first started writing for ITPro in 2007, with bylines in New Scientist, Wired, PC Pro and many more.

Nicole the author of a book about the history of technology, The Long History of the Future.

-

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?

Bigger salaries, more burnout: Is the CISO role in crisis?In-depth CISOs are more stressed than ever before – but why is this and what can be done?

By Kate O'Flaherty Published

-

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25

Cheap cyber crime kits can be bought on the dark web for less than $25News Research from NordVPN shows phishing kits are now widely available on the dark web and via messaging apps like Telegram, and are often selling for less than $25.

By Emma Woollacott Published

-

Meta executive denies hyping up Llama 4 benchmark scores – but what can users expect from the new models?

Meta executive denies hyping up Llama 4 benchmark scores – but what can users expect from the new models?News A senior figure at Meta has denied claims that the tech giant boosted performance metrics for its new Llama 4 AI model range following rumors online.

By Nicole Kobie Published

-

Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis says AI isn’t a ‘silver bullet’ – but within five to ten years its benefits will be undeniable

Google DeepMind’s Demis Hassabis says AI isn’t a ‘silver bullet’ – but within five to ten years its benefits will be undeniableNews Demis Hassabis, CEO at Google DeepMind and one of the UK’s most prominent voices on AI, says AI will bring exciting developments in the coming year.

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

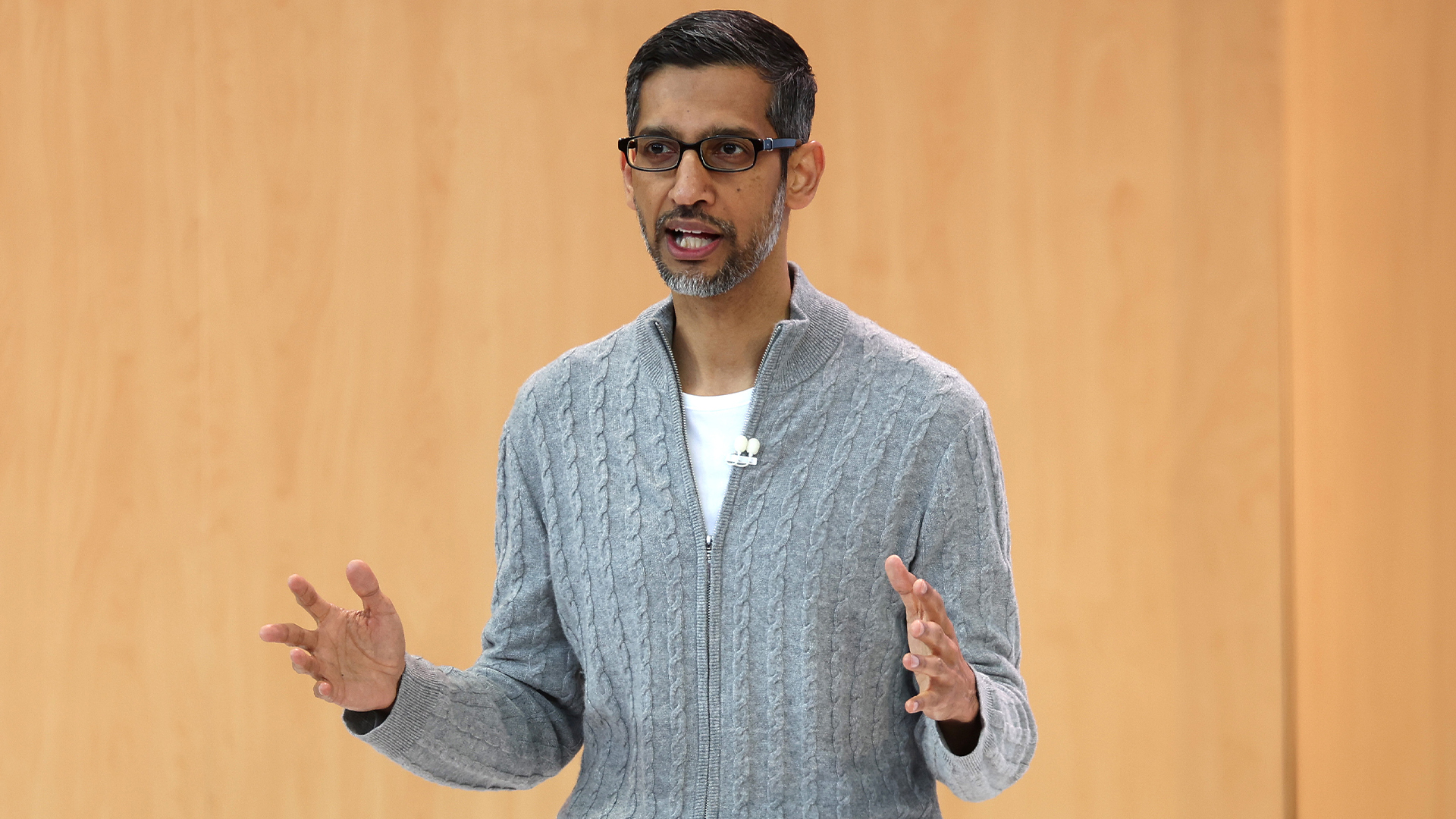

Google CEO Sundar Pichai says DeepSeek has done ‘good work’ showcasing AI model efficiency — and Gemini is going the same way too

Google CEO Sundar Pichai says DeepSeek has done ‘good work’ showcasing AI model efficiency — and Gemini is going the same way tooNews Google CEO Sundar Pichai hailed the DeepSeek model release as a step in the right direction for AI efficiency and accessibility.

By Nicole Kobie Published

-

The DeepSeek bombshell has been a wakeup call for US tech giants

The DeepSeek bombshell has been a wakeup call for US tech giantsOpinion Ross Kelly argues that the recent DeepSeek AI model launches will prompt a rethink on AI development among US tech giants.

By Ross Kelly Published

-

Google will invest a further $1 billion in AI startup Anthropic

Google will invest a further $1 billion in AI startup AnthropicNews This is the latest in a flurry of big tech investments for the AI startup

By George Fitzmaurice Published

-

2024 was the year where AI finally started returning on investment

2024 was the year where AI finally started returning on investmentOpinion It's taken a while, but enterprises are finally beginning to see the benefits of AI

By Ross Kelly Last updated

-

Has Google made a quantum breakthrough?

Has Google made a quantum breakthrough?ITPro Podcast The Willow chip is reported to run laps around even the fastest supercomputers – but the context for these benchmarks reveals only longer-term benefits

By Rory Bathgate Published

-

Google jumps on the agentic AI bandwagon

Google jumps on the agentic AI bandwagonNews Agentic AI is all the rage, and Google wants to get involved

By Nicole Kobie Published